Jon Phillipson

All artworks by Jon Phillipson

Printmaking • 8 artworks

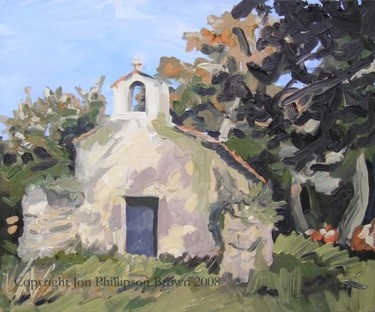

View allLa Vista Consciente • 14 artworks

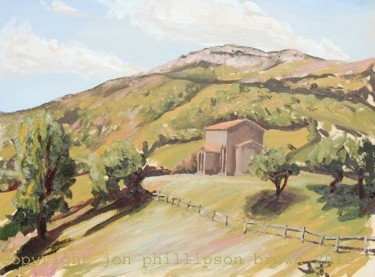

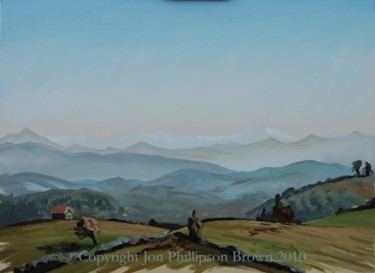

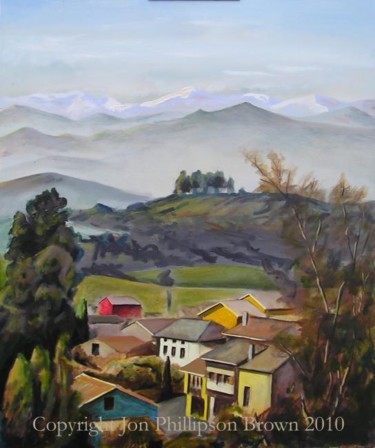

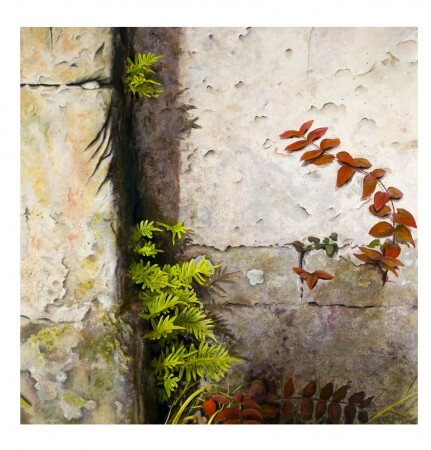

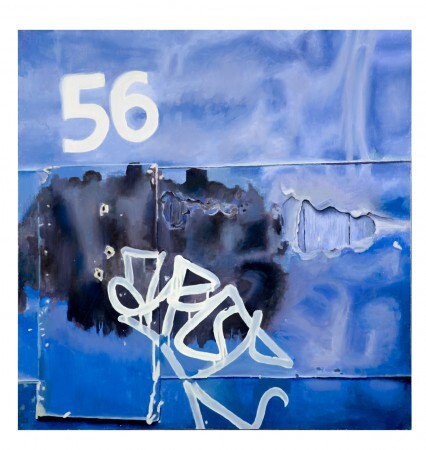

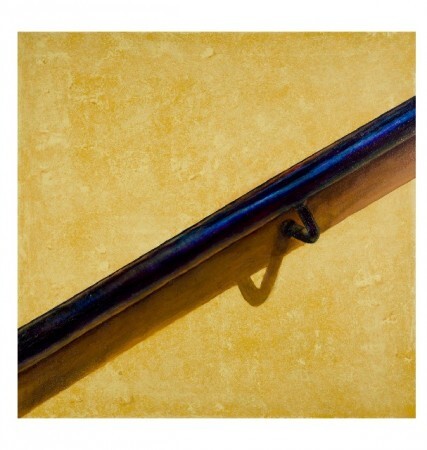

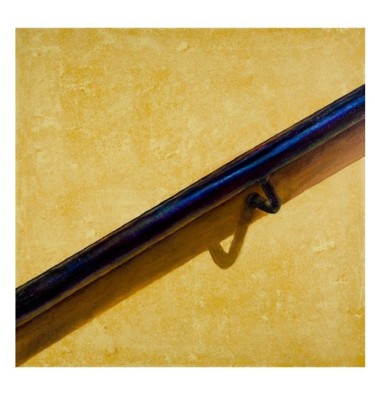

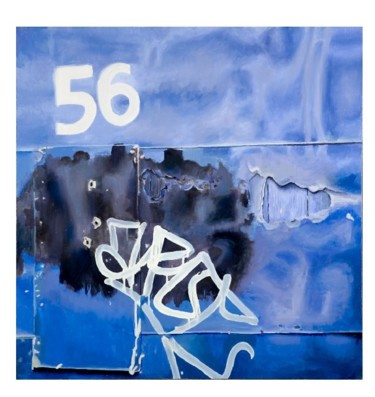

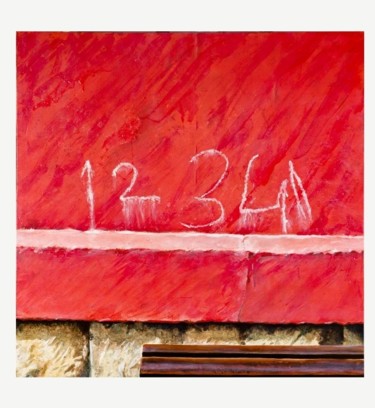

View all“La Vista Consciente” was an exhibition of paintings that toured three Spanish cities: Mieres, Avilés and Gijón in 2010. In the paintings synthetic, rectilinear shapes contrast sharply with organic forms. Broad swathes of primary colours give way to shadows, broken colour and glimpses of tighter, more specific, photographic details. Some paintings show walls, here and there divided by a drainpipe or other architectural feature. They are decorated with bright colours and then further decorated with the calligraphic swirl of graffiti. In other paintings, nature dominates; branches and leaves crowd the picture plane and a wave breaks over a concrete slipway.

Photography and painting, the creative process

Almost all of these paintings were painted during the last three years in my studio near Pola de Siero. They all started life as photographs. The vast majority of these photos were taken in Asturias: many in and around Pola de Siero, several in Gijón, one in Luarca and one in Cudillero

I take many, many photos and I choose a very small proportion of them to turn into paintings. The process of selecting which photos to interpret into paint is crucial. Of course many are filtered out immediately as uninteresting or too obvious. For a host of other, often shifting, criteria, or caprices the selection is winnowed down. As I look through the pictures I listen out for something speaking to me; a combination of colours, shapes or patterns that pulls on my heart and says “paint me”. I try to keep an open mind about what to include, but over time, through the process of working from photos to paintings a number of themes have begun to nag away at me, calling for further clarification, exploration or elaboration and I suppose that now I look out for them and for ways of developing their variations.

These themes include: the walls that surround us, at once limiting and creating the spaces we inhabit; writing on walls, the sublanguage of graffiti; the articulation of a shallow pictorial space, surfaces, realism posing as abstraction, reproduction of painted surfaces, the discovery of beauty in unusual places and sense of wonder at the physical world around us or as William Blake put it

To see a world in a grain of sand,

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

from Auguries of Innocence, William Blake

In the very initial stages of creating a painting I often use a digital projector to transfer the image from the computer to my canvas. Standing up close to the canvas, my hands and arms awash with the image in question, bathed in the light of the projector; I wonder if Johannes Vermeer marvelled at a similar experience in the magical pin-prick light of a camera obscura.

I am very interested in the relation between photography and painting: the qualities they share and the things that mark them apart and also how they can be used together to make art. I might even have chosen to exhibit the original photos, but it would have made for a very different show, a very different experience for the viewer.

For me perhaps one of the most interesting differences between painting and photography relates to the time invested in the production of the work. These paintings have taken many hours to create; some have more than a hundred hours work in them. They are composed of many layers of paint; sometimes these are transparent glazes which create a jewel-like sparkling depth and other times an opaque layer is necessary to correct, clarify or obfuscate. During these hours a protracted decision making process emerges. As the work progresses the painting takes on a reality of its own, and begets its own voice which increasingly demands to be heard. As the English painter Ivon Hitchens wrote:

“The complexities of any one subject have a thousand aspects. The mind sifts them, as through a filter of relativity. Thus a realisation of the essentials, seen in relation to each other, becomes a simplification which it is possible to put on canvas. One or two of those many moments of vision will the most accurately convey something of the complexity I have seen. The canvas receives life, becomes alive, gives back life and finally shows the relativity of Nature. A good painter is he who, like a magician, having taken thought, utters the magic words, and conjures up life from within the canvas.”

Memorandum by Ivon Hitchens as quoted by Peter Koroche in his book “Ivon Hitchens” 2007

Details are filtered, engendering a simplified, customised vision in which some aspects are seized upon for their attractiveness of colour, shape or symbolic content, and then highlighted and rendered in slavish details while others are neglected or consciously omitted, distorted, pushed out-of-focus or described in the most general of forms with the largest of brushes available. There are both plans which come to fruition and those which founder; happy accidents upon which one tries capitalize and true disasters which one regrets.

On Graffiti

I am rapt with the position that graffiti occupies between painting and writing and thought. Of course I revel in the juxtaposition of sub-culture and high-art. The sterility of the gallery is assured, protected from the dirt of the crumbling wall, and its clandestine crime by a thin layer of picture varnish locking them in place like a prehistoric flies trapped in Baltic amber. All the while, I’m vicariously enjoying the illicit subversion of graffiti, safe from the fear of the unseen hand on my shoulder, feeling my collar. The rehearsed, free-flowing spontaneity of graffiti’s gestures tantalize. Its swooping, pigmented aerobatic vapour trails arch and soar rebellious against a rigid architectural sky which frames and ironically supports it. Its out-sized, larger-than-life cursive requiring, in its loops and flicks, not just a “fair-hand” but fair movement and co-ordination of eye, hand, wrist, arm, shoulder, whole-body, I fantasise, balletic and harmoniously allied with the painter’s innate impulse to reach out and express their presence “I woz ere” on any available surface. Isn’t this what people have done since the first artists left their marks at the back of the cave?

Two dimensions versus three dimensions

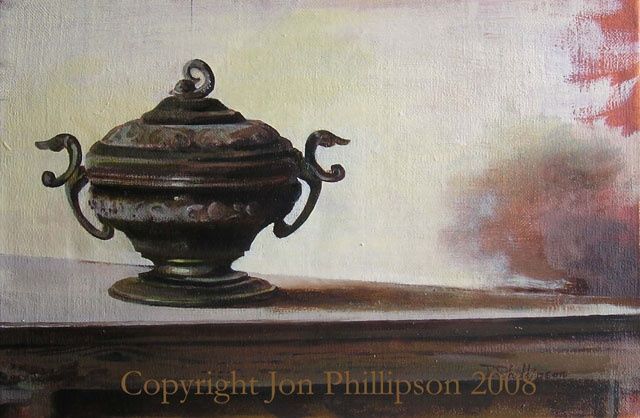

The question of how to create the illusion of space, of a third dimension on the flat plane of the canvas has been a central preoccupation of European painting since before the renaissance. As such it is the kind of issue with which a painter necessarily has a relationship. The space I choose to explore is a shallow but precious one. I want to make the viewer believe in that space behind the varnish and to believe that the objects that inhabit the space enjoy a solidity and could indeed be grasped if the rules of the gallery were to allow it. However, I also strive to create a tension between the enticing illusion of space and the physical presence of the painting as object. The painting exists to seduce the viewer temporarily into the suspension of disbelief and then on the point of reaching out to touch, the objects of desire are snatched away, the spell is broken, the illusion shattered as the space and forms dissolve into mere luscious paint, gobs of colour, daubed contours of its surface, its strokes, scratches, and impasto. I believe that the best painting uses that kind of tension to keep the viewer’s mind-gaze rebounding between the two states.

I try to find a balance between on the one hand a fully resolved, recognisable image, and a more abstract form where the success criteria are harder to pin down and have more to do which achieving a harmonious unity within the picture plane than with the painting resembling anything “real”.

I struggle backward and forward with this kind of issue. Whilst painting the Fig Leaves painting, for example, I noted that I wanted to choose some foreground leaves and treat them in a more mechanistic, highly detailed way to make them seem to “come into focus” but then reflected that I didn’t then want to have to tighten-up the whole of the painting as it possessed a lot of “blobby” sweepy lines that don’t quite make sense; imperfections, errors or clumsinesses in themselves; but which within the context of the whole, add rather than detract. I feel that the fig tree is like that: awkward, grotesque and highly idiosyncratic.

Equanimity

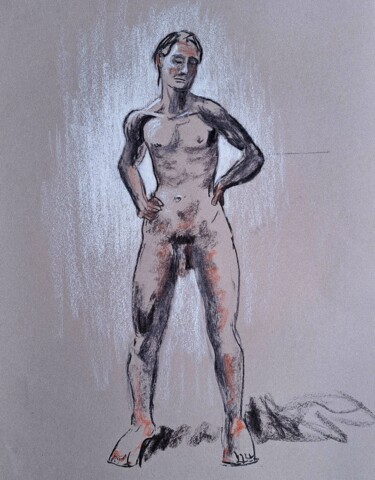

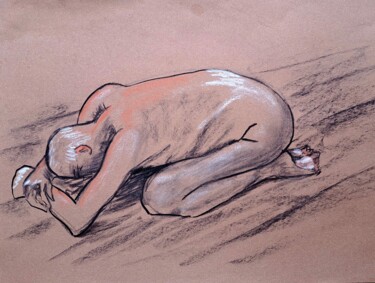

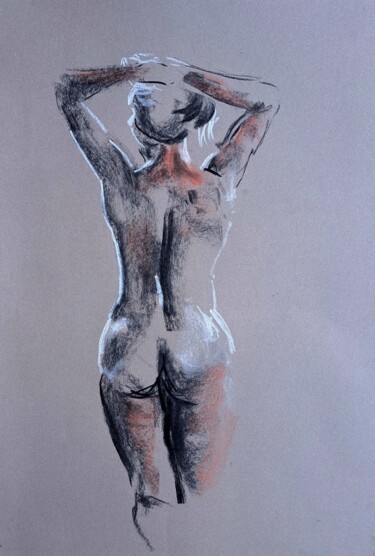

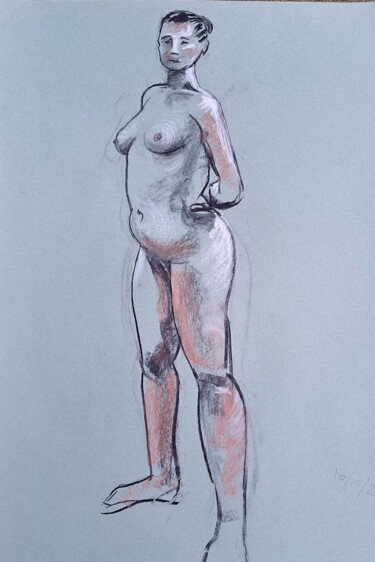

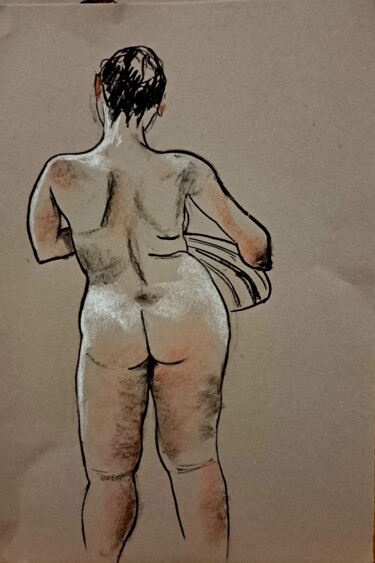

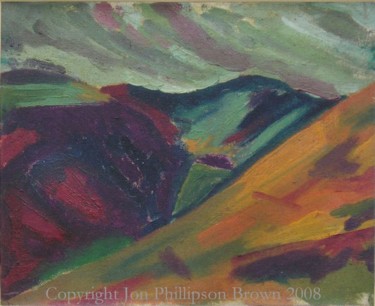

Several of the paintings are titled ”Equanimity” as it represents an important idea for me, in fact I nearly gave the same title to all the paintings in the show. What I’m hoping to suggest is something of an equanimous vision wherein different phenomena, aspects of life or emotional states can be met with a level, unflinching gaze. A gaze which is supported by a kind of composure which is neither reactive nor easily shaken. In this, I seek to build on what was a fundamental tenet of my own art education. I was taught that to learn to paint is in essence a process of learning to look, to see clearly. All good art has its basis in observation, we learnt. I now understand this to refer to observation in the widest possible sense. It could be, as it was those years ago in the art school studio, the observation of how the light of day reveals the musculature of the human body; or it could be the observation of how patterns emerge within the structure of our society, or the observation of how one feels immersed in the experience of being within a landscape, on a hillside exposed to the wind and rain; this observation might even extend to the witnessing of all that one can experience whilst seated in silent meditation. In all cases what is essential is that the observation should be scrupulous, rigorous and clear, this requires an equanimous composure. This composure, to which one might aspire, would not be disturbed by some tempestuous scene, nor seduced by the appearance of harmonious tranquillity, but would provide one with a soft spaciousness of mind that would be able to contain anything that arises.

More and more I think of painting as a meditative activity in which one has to involve oneself 100%, to the exclusion of all else, and go as far as one can with that level of commitment, believing in oneself without admitting any doubt as to the validity of one’s convictions. Having done that, one then has to train oneself to step back and look at what has been done with honesty, and with an open mind through which one can learn, develop and grow. Leaving behind prejudices and preconceived ideas I seek to face the world with the fresh eye of a child supported by the mental stability of an adult.

“I am always obliged to go and gaze at a blade of grass, a pine tree branch, an ear of wheat, to calm myself” – Vincent Van Gogh letter to his Sister Wil (letter number 785)

O how my heart is lifted! • 15 artworks

View allIn this series of paintings I am trying to create a harmony between the fresh, exuberant vitality of the blossom, the elation I feel within on seeing it, and an energetic, gestural handling of the paint. I call this series of paintings “O how my heart is lifted!”

Navecopyright.jpg?v=1739653455)