Added May 20, 2025

The strategic use of symbols in art and design transcends mere decoration: symbols carry culturally and psychologically embedded meanings that shape how individuals perceive and interact with spaces. When deployed intentionally, symbols can foster experiences of power, luxury, and beauty; when used inadvertently or inappropriately, they may trigger negative associations, even repulsion, among viewers. This blog examines the academic foundations of symbolism in environmental perception, explores how unintended symbols undermine harmony, and outlines best practices for intentional symbology—exemplified by the Hueb approach—to harmonize environments and elevate aesthetic impact.

1. Theoretical Foundations: Semiotics and Environmental Psychology

Semiotics posits that meaning arises through the relationship between the signifier (the symbol’s form) and the signified (the concept it represents). According to Proshansky et al. (1972), symbolic meanings are a fundamental mode through which humans relate to physical settings: they “shape people’s understanding of the world and motivate their purposes, attitudes, and actions” Frontiers. Environmental psychology extends this insight by examining how symbols within spaces influence affective and cognitive responses. For example, studies in environmental design demonstrate that symbolic elements—such as repeated geometric motifs—can modulate perceptions of order, stability, and serenity in built environments JSTOR.

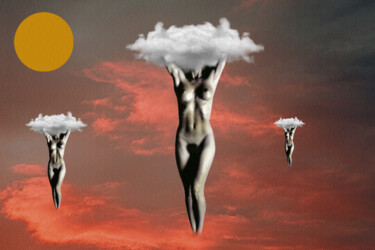

2. Cultural and Archetypal Symbols: Sources of Harmony

Certain symbols enjoy near-universal recognition as embodiments of harmony and balance. The mandala, for instance, is rooted in Jungian psychology as an archetype of wholeness and integration; its radial symmetry can induce meditative calm and a sense of unity in viewers. Similarly, the Yin-Yang symbol encapsulates complementary dualities—light/dark, active/passive—reminding observers that harmony emerges from balanced contrast. Such archetypal symbols leverage deep-seated neural and cultural schemas to evoke equilibrium and aesthetic pleasure Dreamers Guides.

3. Inadvertent Negative Symbolism: When Art Repels

Artists may unknowingly incorporate symbols with adverse connotations. Research on indigenous and social symbols reveals that “misappropriation, misuse and misinterpretation of symbols with their original intentions” can lead to cultural dissonance and viewer discomfort ResearchGate. Moreover, Perception Creation Using Symbolic Management notes a critical gap: “there has been no research as to how symbols created in this manner affect people when used in conjunction with other symbols in a single environment,” indicating that conflicting symbol clusters can generate cognitive dissonance and emotional repulsion Digital Commons. For example, a decorative motif resembling a culturally sensitive emblem—used without contextual awareness—can inadvertently alienate or offend segments of an audience.

4. Symbolic Synergy and Contextual Interaction

Symbolic perception is not strictly additive; the interplay among multiple symbols within a space can amplify or negate individual meanings. Frontiers in Psychology emphasizes that symbols “in conjunction with other symbols in a single environment” can produce emergent interpretations not predictable from isolated signifiers Digital Commons. This synergy underscores the importance of curating symbol sets holistically: a luxury interior may blend sleek metallic textures (symbolizing modernity and strength) with classical motifs like laurel wreaths (symbolizing victory and prestige), thus reinforcing an overarching narrative of exclusivity. Conversely, pairing a minimalistic geometry with incongruent folk symbols could fracture the desired perception, diluting the sense of cohesion and diminishing emotional resonance.

5. Neurological and Emotional Processing of Symbols

Neuroaesthetic research suggests that symbolic forms engage both affective (limbic) and cognitive (prefrontal) pathways. Visual stimuli with high symbolic relevance activate neural networks associated with memory, emotion, and meaning-making, resulting in deeper engagement and prolonged attention. Lamprecht’s work on ornament in environmental psychology argues that hand-crafted symbols satisfy our need for “engagement and meaning,” triggering dopamine release linked to novelty and recognition Modern Resources. Conversely, ambiguous or conflicting symbols can heighten amygdala response, eliciting anxiety or aversion. Thus, intentional symbol choice guides emotional trajectories within a space.

6. Case Study: Negative Symbolism in Commercial Spaces

Consider a gallery installation where abstract motifs unintentionally resembled biohazard icons. Though aesthetically compelling, several visitors reported unease, associating the forms with danger. Post-exhibit surveys revealed that even subconscious recognition of negative symbols can overshadow conscious appreciation of technique. This phenomenon aligns with the dual-process model of perception: rapid, implicit evaluation flagged the shapes as threatening before conscious reappraisal could occur, compromising overall experience.

7. The Hueb Approach: Deliberate Symbology for Power and Luxury

At Hueb Arts, symbols are employed not as arbitrary decoration but as intentional carriers of power, prestige, and aesthetic beauty. The Hueb approach integrates three key principles:

Neuro-Resonance: Selecting symbols proven to engage neural reward circuits (e.g., gold leaf accents, mandala geometries).

Jungian Archetypes: Invoking collective unconscious motifs (e.g., the Sovereign’s crown, the Alchemical phoenix) to evoke empowerment and transformation.

Contextual Coherence: Ensuring all symbols within a composition share thematic lineage (e.g., victory, purity, transcendence) to prevent semantic discord.

By aligning symbol selection with both neuroscience and archetypal theory, Hueb Arts synthesizes environments that elicit immediate emotional impact while sustaining intellectual engagement.

8. Guidelines for Intentional Symbol Use

Drawing from the above, artists and designers should adhere to the following best practices:

Conduct Symbolic Audits

Inventory all motifs and research their cultural and emotional associations.

Use academic databases (e.g., JSTOR, PubMed) to verify symbol origins and contemporary interpretations JSTOR.

Evaluate Symbolic Interactions

Perform mock-up layouts with clustered symbol groupings.

Solicit feedback from diverse focus groups to identify unintended connotations.

Align with Emotional Objectives

Define desired audience response (e.g., empowerment, tranquility).

Select symbols documented to evoke those responses—consult color-psychology and neuroaesthetic literature.

Maintain Thematic Coherence

Ensure every symbol reinforces a unified narrative (power, harmony, luxury).

Avoid incongruent pairings that may trigger cognitive dissonance.

Iterate with Empirical Testing

Employ eye-tracking or neuroimaging studies for high-stakes installations.

Adjust symbol size, placement, and context based on measured engagement metrics.

9. Future Directions in Symbolic Environmental Design

Emerging research should address gaps in our understanding of multi-symbol environments. Longitudinal studies combining Difference-in-Differences (DiD) methodologies could compare viewer responses to spaces before and after symbolic redesign, quantifying changes in perceived harmony and psychological comfort. Additionally, cross-cultural evaluations would clarify how globalized audiences negotiate universal versus culturally specific symbols.

Conclusion

Symbols wield profound influence over environmental perception. Left to chance, they risk undermining harmony and alienating viewers; used with scholarly rigor and intentionality—as exemplified by the Hueb approach—they can imbue spaces with power, luxury, and enduring beauty. By grounding symbol selection in semiotics, environmental psychology, and neuroaesthetics, artists ensure that every motif contributes cohesively to the intended emotional and cognitive impact, transforming mere decoration into a resonant language of meaning.

References

Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., & Kaminoff, R. (1972). The dynamics of symbolic meaning in environmental perception. Frontiers in Psychology.

“Symbolism and Environmental Design.” JSTOR.

Perception Creation Using Symbolic Management. Digital Commons, University of Denver.

“Symbolic Perception Transformation and Interpretation,” ResearchGate.

Lamprecht, B. (2016). Ornament in the realm of environmental psychology.