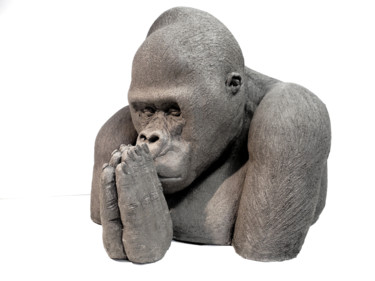

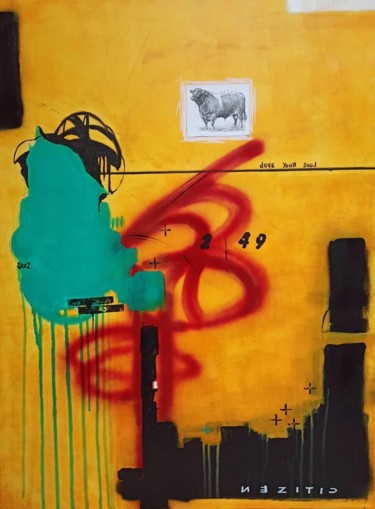

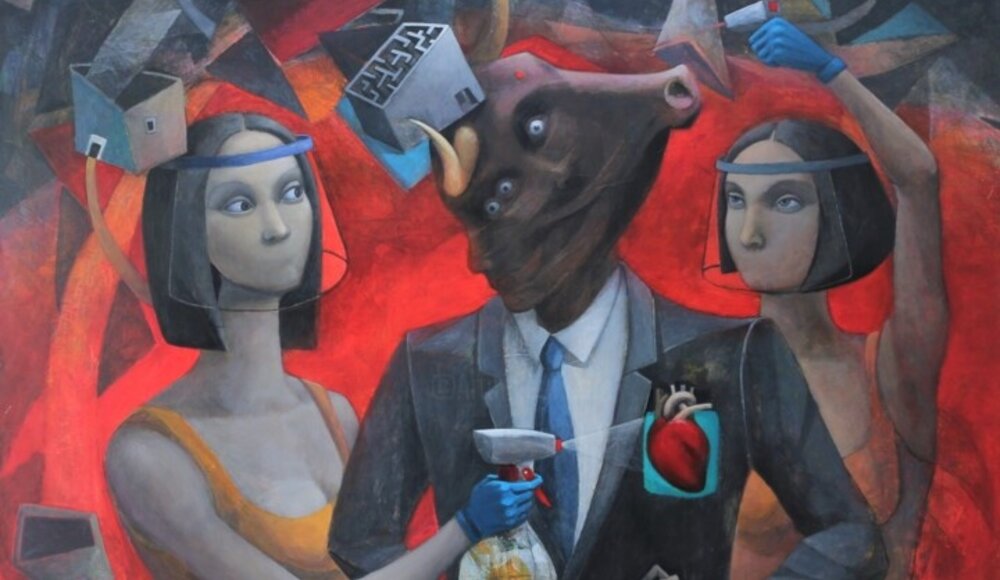

Hector Acevedo, Minotaur Protocole, 2021. Oil on canvas, 150 x 150 cm.

Hector Acevedo, Minotaur Protocole, 2021. Oil on canvas, 150 x 150 cm.

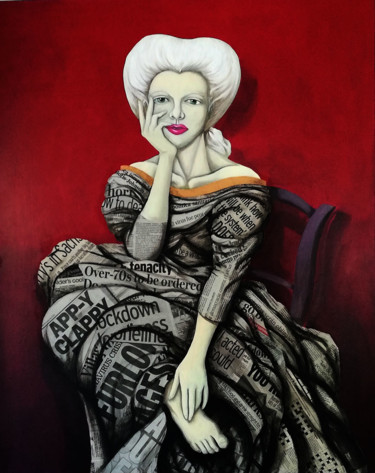

Jrmuroart, David at the garage, 2018. Oil on wood, 97 x 130 cm.

Jrmuroart, David at the garage, 2018. Oil on wood, 97 x 130 cm.

Over the centuries Spain has given birth to some of the world's greatest architects, painters, sculptors and photographers. This richness is due, both to the autonomous Spanish creative flair and to the influence exerted on the Iberian Peninsula by the most important European figurative currents. Speaking of the origins of Spanish art history, it turns out to have very deep roots, found as far back as prehistoric times. In fact, dating back to the first phase of man's artistic production, datable between 30000 and 8000 B.C. and placeable in the Upper Paleolithic period, are the Franco-Cantabrian cave paintings of southern France and the Spanish Cantabrian coast. The main subject of this type of artistic production is the fauna of the time, namely bison, horses, bats, etc., figures depicted mostly in isolation or juxtaposed. The interpretation of these paintings is linked to the sphere of ritual, as the hunter-man believed that by representing the aforementioned beasts, he would also ensure their capture. One of the most relevant examples of Iberian Franco-Cantabrian art is surely the Altamira Caves, discovered in 1875 by Marcelino Sanz de Santuola. Continuing the narrative on the history of Spanish art, between the Mesolithic and the Metal Age, Levantine painting became established, which, generally placed inside rock shelters open to the outside, used to immortalize subjects of a more narrative nature, that is, scenes animated by characters, aimed at recounting the routine life of the tribes. Among the many examples of Levantine painting, that of the shelter of Roca dels Mors in Cogull (Lérida) is certainly noteworthy, decorated with a scene formed by a group of women, who, around a man, engage in a kind of ritual dance related to fertility. Later on, and more precisely from the 21st century B.C. until the 3rd century B.C., there followed in Spanish art the influences brought by the schematic painting, megalithism and Tartesian art, as well as trends coming from the Phoenicians, the Carthaginians, the Greeks, the Iberians and the Celts, civilizations that subjugated the Iberian Peninsula. Subsequently, the Spanish cultural baggage continued to be enriched by further external influences; in fact, the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula (218 B.C.-17 B.C.) brought to Spanish art its most typical mixture of Etruscan and Greek tendencies, realized in works with mainly public intentions. Examples of what has just been stated can be found in the archaeological sites of early Spanish Roman cities, such as Italica, Mérida, Tarragona and Astorga, as well as in Almedinilla, La Alcudia, Alcolea del Río, Osuna, Carmona and so on. In addition, it is worth highlighting how, in addition to painting and architecture, the Roman model also spread to Spain through sculpture and mosaic art. Following this, further enrichment of Spanish art was brought about by Visigothic and Muslim domination, after which the following styles imposed themselves in succession: Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Mannerist.

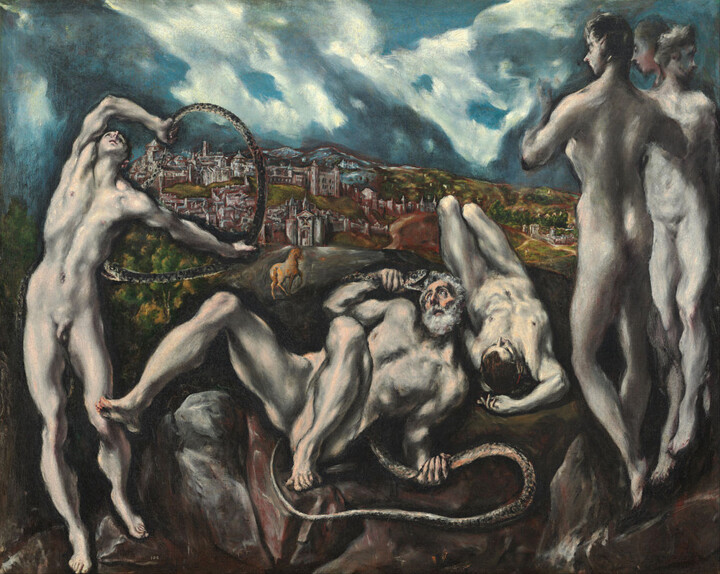

El Greco, Laocoonte, 1610-14. Oil on canvas, 142 x 193 cm.

El Greco, Laocoonte, 1610-14. Oil on canvas, 142 x 193 cm.

Francisco Goya, Saturn devouring his children, 1821-23. Oil on canvas, 146 x 83 cm.

Francisco Goya, Saturn devouring his children, 1821-23. Oil on canvas, 146 x 83 cm.

During the Romanesque period, painterly flair manifested itself mainly in the illumination of manuscripts and frescoes in church vaults, just like the crypt of the Basilica of San Isidro in Leon, where some of the best-preserved 12th-century paintings in the world can be found. Speaking of the Gothic, however, during this period the aforementioned type of wall paintings continued to be popular, although, nevertheless, the figures were enriched with greater expressiveness and movement, even becoming smaller than the background. Nevertheless, illuminated manuscripts continued to be the most popular works at the time, although there was no shortage of rich examples of panel paintings, frescoes, and stained glass windows. As for the Spanish Renaissance, the art of the time strongly, and predominantly, directed its attentions toward the Italian model, reflecting its innovations and stylistic features. Subsequently, the period of the High Renaissance, referred to as Mannerist, was indelibly marked by the presence of one of the most important personalities of Spanish art: the painter El Greco, who, despite being of Greek origin, was accepted into Spanish culture, as he spent most of his life living and working in Toledo, Spain. Famous artists of the later currents of Baroque and Romanticism, on the other hand, were Diego Velazquez, belonging to the former, and Francisco Goya, a well-known exponent of the latter. Finally, reaching the 20th century, Spanish art continued to make headlines through the work of great masters such as Pablo Picasso, the father of Cubism, and Salvador Dali, the greatest exponent of Surrealism. Finally, the narrative on the history of Spanish art can only be ended through the mention of other fundamental artists who contributed to making the name of spain great within the figurative arts, such as Juan de Valdés Leal, Julio González, Joan Miró, Juan Gris, and many more...

Benito Leal Gallardo, Ermitaño, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Benito Leal Gallardo, Ermitaño, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Tomasa Martin, Observatorio. Acrylic / oil on wood, 44 x 44 cm.

Tomasa Martin, Observatorio. Acrylic / oil on wood, 44 x 44 cm.

Contemporary Spanish art

Within contemporary reality, among the many artists capable of carrying on the great Spanish figurative tradition, it is worth noting: Miquel Barceló Artigues, a painter known for his particularly complex vision of reality, in which skeletal African primitivism, Majorcan ethnographic elements and precarious Parisian modernity are interwoven; Josep Royo, a contemporary Catalan artist known for his tapestries; Lita Cabellut, a multidisciplinary artist who works on large canvases using a contemporary variation of the fresco technique; Manolo Valdés, an eclectic painter who has introduced a form of expression in Spain aimed at combining political and social obligations through humor and irony. In addition, to the important points of view mentioned above we can undoubtedly add those of the Spanish artists of Artmajeur, well exemplified by the work of Roberto Canduela, Lídia Vives and Gus - Fine Art.

Roberto Canduela, Convex spaces tauro 3, 2021. Sculpture, metals on stone, 23 x 19 x 12 / 1.00 kg.

Roberto Canduela, Convex spaces tauro 3, 2021. Sculpture, metals on stone, 23 x 19 x 12 / 1.00 kg.

Roberto Canduela: Convex spaces tauro 3

Roberto Canduela is an emerging Spanish sculptor whose artistic investigation draws inspiration from classical forms, which are related, compared and juxtaposed with modernity through an exercise in simplification. The objective of such a way of working is to summarize, through abstraction, the human subconscious animated by the relationship that is established between man and the work of art. Precisely, his sculptures, pursuing this purpose, are designed to attract the viewer's attention through their magnetic form and presence. Trying to further analyze the artist's work, it is possible to refer to the sculpture Convex spaces tauro 3, within which he combines contemporary language with one of the oldest and most popular themes in the history of Spanish art, namely the tauromachy, indicated by the very title of the work. Indeed, among the many masters passionate about the aforementioned topic we cannot help but mention the well-known Francisco Goya and, in particular, Temeridad de Martincho en la plaza de Zaragoza, eighteenth of his forty engravings in the graphic series dedicated to bullfighting. It is precisely in this context that it emerges forcefully how, unlike the "peaceful" and "abstract" sculpture by the artist from Armajeur, this latter realist masterpiece tends to highlight the aggressive power of the bull, ready to attack the well-known bullfighter Francisco Antonio Ebassún Martínez.

Lídia Vives, Separation of property, 2022. Digital photograph on aluminum, 80 x 53 cm.

Lídia Vives, Separation of property, 2022. Digital photograph on aluminum, 80 x 53 cm.

Lídia Vives: Separation of property

The production of the Spanish Lídia Vives, an advertising and fashion photographer as well as an artist, has been strongly influenced by the Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters, as well as by some contemporary artists. In fact, her photographic investigation is marked by a great attention and care directed toward the choice of colors, compositions and environments, aimed at immortalizing topical issues, as well as the exploration of the genre of the self-portrait. Precisely these peculiarities, well expressed by the work Separation of property, have made the artist's work interesting for famous fashion magazines, such as Esquire and Vogue. In this context, it seems necessary to open a small parenthesis on fashion photography, an art form that originated in the 19th century, thanks to the iconic fashion La mode practique (1898), Harper Bazar (1867) and Vogue (1892). Nevertheless, it was not until the 20th century, the latter genre gained a new status, mainly related to the increased public interest in designers' fashion shows and collections.

Gus - Fine Art, Spring rain. Digital photograph / manipulated photograph on paper, 70 x 105 cm.

Gus - Fine Art, Spring rain. Digital photograph / manipulated photograph on paper, 70 x 105 cm.

Gus - Fine Art: Spring rain

Gus, a Spanish visual artist and photographer whose figurative production turns out to be largely influenced by Impressionism and contemporary art, often combines ancient and modern techniques, pursuing the goal of creating complex images, that is, composed of multiple layers, meticulously executed and visually captivating. It is precisely these peculiarities that allow Gus's work to take the viewer on a journey within the artist's imaginative depths, where photographic compositions, multiple exposures, and matte painting are combined. Regarding the Spring rain shot, it manifests, as well as others performed by the artist, Gus's love of rain, a peculiarity he shares with Jim Richardson, a well-known photographer for The National Geographic Magazine famous for the famous phrase, "When it starts to rain, good photographers go out and take pictures."

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli