Nikolaus Weiler, Sinus Column, 2018. Sculpture, Wood on Metal, 37 x 7 x 4 cm / 0.30 kg.

Nikolaus Weiler, Sinus Column, 2018. Sculpture, Wood on Metal, 37 x 7 x 4 cm / 0.30 kg.

Amedeo Modigliani, Standing Caryatid, 1913. Oil on canvas, 81 x 45. Private collection.

Amedeo Modigliani, Standing Caryatid, 1913. Oil on canvas, 81 x 45. Private collection.

Let us begin by clearly stating how Western art, as we know it today, would not have been explicated in its forms, whether today or earlier, if it had not taken into account the Greek model, that is, that first civilization that conceived of art as a medium, which, sometimes even unusually independent of the propaganda of religion and power strove to emphasize the beauty and complexity of the human body, through an aesthetic taste that remained the basis of all subsequent creative pursuits, both figurative and abstract, in that, even those who exulate from formal depiction, do so conscious of its existence. Talking about Greek art, however, often means repeating oneself and falling into the classic clichés, that is, narrating the evolution of styles and describing the greatest masterpieces of classical and Hellenic sculpture and architecture. Therefore, as I often do, I wanted to eschew a stereotypical narrative, which, although fascinating, inescapable, rich and decisive risks being read, in different words and interpretations, on various and multiple websites, magazines, social media, books, etc. My purpose is, once again, to amaze the reader, to interest him more, hoping, perhaps, to actually leave him with a little cultural baggage that is resistant even to the most varied modes of memory erasure inherent in human beings. In order to accomplish the above, I have taken three fundamental elements of Greek architecture, such as caryatids, capitals and columns, and researched them in some of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art, works that, in addition to showing the eternal impact of the classical model, provide us with new insights into the Greek world. Speaking of caryatids, knowledge of these figures, usually female, carved to be used as columns or pillars supporting architectural members, is generally associated with the more traditional buildings specimens, which, of due Greek provenance, reach their highest expression in the loggia of the Caryatids of the Erechtheion in Athens. Animating the latter context, we can imagine how, without any warning, the aforementioned women, probably curious about the features of the world, decide to abandon their burdensome task, detaching themselves from the lintel and separating permanently from each other, in search of a new, and perhaps lighter, reason for living. What has been said brings to mind the solitary interpretations of caryatids by Amedeo Modigliani, an artist who devoted himself to this theme between 1912 and 1914, making sculptures and oils, which analyzed the aforementioned figure in the grip of a sort of identity crisis, as it seems to be still intent on supporting an architecture, which, now nonexistent, does not justify the physical effort of its position. In addition, Modigliani's caryatids reveal themselves, for the first time in history, as forms of extreme softness and roundness, true columns of tenderness, made with essential and expressive lines, which the masses generally compare with the better-known, calm and realistic Greek models, although, in reality, the Italian artist drew more inspiration from Etruscan and African statuary. Arguably, more closely related to the Greek caryatid model was Auguste Rodin, just as would be inferred from The Fallen Caryatid Carrying Her Stone, a sculpture, which, subsequent to the first executions of the subject, dating between 1871 and 1877, was conceived while the artist was working on the project of The Gates of Hell, understanding it, for the first time, as a figure crushed and defeated by the weight of a rock. The protagonist of the work, whose mighty body is crouched down, is meant to symbolize the human being, who, at the mercy of the weight of his fate, continues to struggle with dignity and courage in order to carry out his task: to try to live. Returning for a moment to the context of ancient Greece, it is good to highlight how the male caryatids were referred to by the appellation telamon, a synonym for Atlas, a mythological figure aimed at supporting the earth.

Beato Angelico, Annunciation of the north corridor, 1440-50. Fresco. Florence: Convent of San Marco.

Beato Angelico, Annunciation of the north corridor, 1440-50. Fresco. Florence: Convent of San Marco.

Moving from caryatids to capitals, the latter upper part of the column or pillar had, in Greek culture, a function of first importance, since in it was synthesized the concept of harmonizing the column with its respective entablature. This viewpoint found a following in the Italian Renaissance, a period during which the exaltation of the beauty and workmanship of the aforementioned reached unprecedented heights, as the satisfaction of a purely aesthetic need was imposed on the construction problem. As far as orders are concerned, not all forms of capitals met with equal success in the aforementioned period, so much so that the Doric and Ionic interested almost exclusively the sixteenth century, while the Corinthian and composite had a more constant application throughout the Renaissance period. Evidence of the revival of the Corinthian capital, for mere decorative use, is given to us by the faux-architecture, as pictorial, realized in the loggia of Beato Angelico's Annunciation, a fresco of about 1425 located at the Convent of San Marco in Florence, Italy. Three other works by the latter master, having the same subject, confirm the interest in such a form of "decorativism," while, to talk about Greek columns we refer to a twentieth-century artist: Giorgio de Chirico. An "anthropomorphic" column, whose grooves are purely of Greek derivation, finds its place in The Disquieting Muses, oil on canvas of 1918, characterized by the presence of all the metaphysical themes that have distinguished the figurative investigation of the Italian master, such as: mannequins, classical quotations, the deserted square and symbols of modernity, such as, in this case, factories, aimed at creating an unsettling bridge between past and present. Finally, the analysis of the work of Artmajeur artists led me to a new investigation, aimed at interpreting the Greek ruins of the past caught through the eyes of contemporary painters such as, for example, Fikret Özcan, Yury Peshkov and Muriel Cayet.

Zahar Kondratyuk, Antique head and column, 2022. Acrylic on Canvas, 160 x 100 cm.

Zahar Kondratyuk, Antique head and column, 2022. Acrylic on Canvas, 160 x 100 cm.

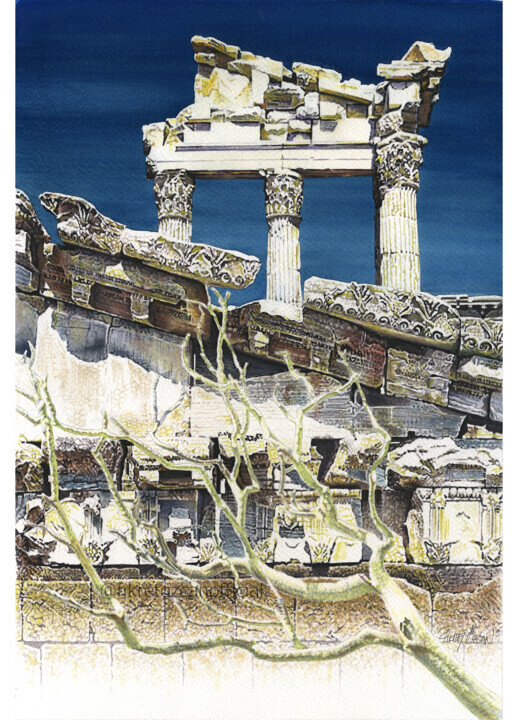

Fikret Özcan, Pergamon-2, 2017. Watercolor on Paper, 40 x 27 cm.

Fikret Özcan, Pergamon-2, 2017. Watercolor on Paper, 40 x 27 cm.

Fikret Özcan: Pergamon 2

Özcan's accurate watercolor reveals, in very rather poetic fashion, the ruins of a time that was, aimed at reminding us, through the nefarious passage of events, of the greatness of an ancient Greece, which is presented to us by "synecdoche," that is, by showing what remains of the rich and powerful city of Moesia, Pergamon, now located northwest of Bergama, precisely in present-day Turkey. This viewpoint echoes in my head the words of Gustave Flaubert, who identified ruins as a magical instrument, capable of "making a landscape dream and give it poetry." If the well-known French writer put such a thought into words, also aimed at communicating an intrinsic charm laden with ambiguity, incompleteness and precariousness, inherent in the very essence of archaeological remains, eighteenth-century painters and engravers anticipated it, promoting the aesthetics of ruins, a cultural stimulus that, in addition to invading works of art, was rampant in archaeological research and in the travels of the young scions of the European aristocracy, aimed at discovering the most famous "ruins" of civilization. In the latter figurative context, some masterpieces even came to include the human figure, which, juxtaposed with the remains of a grandiose time, used to highlight all the insignificance of the over-mentioned species. An example of the above is given to us by the sanguine, titled The Artist Moved by the Greatness of Ancient Ruins (1778-80), by Johann Heinrich Füssli, in which a man is moved by the ruins of another ancient and splendid civilization: the Roman. Finally, I invite you to contemplate the work of Artmajeur's artist by echoing in your mind the iconic words of philosopher Stefano Zecchi: "Life possesses a priceless moral cleanness: everything ends. Sometimes it has the generosity to still grant something before everything is swept away: ruins. Remains of the past that bear witness to the path of history."

Yury Peshkov, Apollo Temple. Cyprus, 2022. Oil on Paper, 40 x 30 cm.

Yury Peshkov, Apollo Temple. Cyprus, 2022. Oil on Paper, 40 x 30 cm.

Yury Peshkov: Apollo temple. Cyprus

The remains of the temple of Apollo appear, in Peshkov's studied pictorial framing, as the vision of a kind of model, who, skillfully directed by the artist, brings her chin up to proudly scan the horizon. Precisely in the same way, the ruins of the ancient sacred site show all their strength, confidence and determination because, although they have come down to us only partially, they have had the privilege of enduring the passage of epochs, customs and historical shifts in the most impassive of muteness. Regarding the site portrayed by the work, it is important to point out that it is the temple of Apollo Hylates, which, located to the west of the ancient city of Kourion, was one of the main religious centers of ancient Cyprus, within which Apollo was worshipped as the god of the Woods. In fact, the very addition of the appellation Hylates referred to a deity, who, exclusively worshipped on the island of Cyprus between the third century B.C. and the third century A.D., was only later assimilated to the more official Greek god Apollo. Finally, what is to date visible of the temple dedicated to the latter is the result, in part, of restorations in the first century A.D., whereas, if one wants to refer to the original structure, it consisted of a circular monument, an archaic altar and a temple, which were later enlarged and enriched in Roman times. Therefore, the work of the artist from Artmajeur fosters, as is well evident from when investigated above, the study of ancient civilizations, as well as the spread of the love of culture and interests in archaeology and art-history.

Muriel Cayet, Temple bleu, 2011. Painting, 20 x 20 cm.

Muriel Cayet, Temple bleu, 2011. Painting, 20 x 20 cm.

Muriel Cayet: Blue Temple

The ancient sacred building depicted in Cayet's painting reminds us, color aside, of the features of the Temple of Concord, an example of mature Doric, which was erected in the Valley of the Temples in Agrigento, Italy, in 430 B.C. To tell the truth, however, this last chromatic judgment turns out to be rather superficial, for although it is indisputable that the predominance of blue in Cayet turns out to be rather surreal and far-fetched, it is imperative to reveal how, probably and originally, the color blue was actually part of the said architecture. In fact, according to one of the most recent expert hypotheses, the actual golden hue of the stone was, antecedently, concealed by a white plaster, which was arranged over the entire structure except for the frieze and gable decorated in blue and red. However, this Pop revelation is perhaps dwarfed by the attitude the Greeks had toward the color of the sky, as they struggled to identify it with a specific word. For example, if we refer to Homer, only four colors appear in his works: white, gray, with shades up to black, red and yellow-green. It is necessary to highlight, however, that within Greek culture, there was the more general predisposition to indicate and refer to brightness rather than hue, so much so that there was no sort of "aversion" against blue, but a simpler disinterest in defining colors clearly and unambiguously.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli