Since the 19th century, sculpture has undergone significant transformations, particularly with the introduction of new materials and techniques that have expanded the boundaries of this art form. The following century marked a turning point with modernist movements challenging conventional approaches to sculpture. Artists began experimenting with non-traditional materials such as iron, steel, and plaster, inspired by industrialization and technological advancements.

Furthermore, the advent of synthetic materials like resin, plastic, and fiberglass opened new possibilities for sculptors. These lightweight and highly adaptable materials enabled the creation of intricate designs, bold colors, and experimental techniques.

Between the late 20th and early 21st centuries, materials like cement, concrete, and aluminum gained prominence, reflecting a shift toward architectural influences and large-scale public installations. Contemporary artists often combine traditional and modern materials, exploring themes related to identity, ecology, and social commentary.

It becomes evident, therefore, that from the 19th century to today, sculpture has evolved from its classical roots into a dynamic and multifaceted art form. Every material introduced over time, whether traditional or modern, has contributed to redefining the possibilities of artistic expression, reflecting the cultural, technological, and philosophical changes of each era.

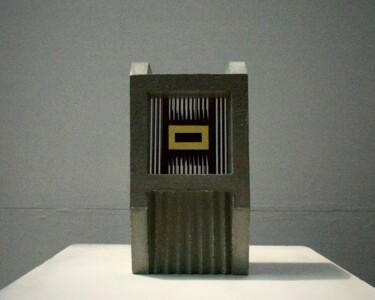

ZOE BRUTALIST HEAD (2024) Sculpture by Paolo Castagna (Brutalist Design)

Concrete and Italian Brutalism

Concrete, often overlooked in artistic and architectural narratives in favor of more "noble" materials like marble or wood, has actually played a pivotal role in a bold and decisive revolution. In Italy, its adoption marked a significant turning point in modern and post-war architecture, introducing radical innovations that reshaped the urban landscape. At the heart of this movement lies Brutalism, an approach that celebrates béton brut, or raw concrete, not only as a structural foundation but also as a powerful means of aesthetic and philosophical expression. Brutalism transforms concrete into a symbol of strength and architectural sincerity, revealing the intrinsic energy of an era that dared to break with the past in order to shape the future.

But let’s take a step back: how and where did Brutalism come to life?

This daring architectural style, named after the French phrase béton brut—meaning "raw concrete"—emerged powerfully in the 1950s and 1960s. Characterized by the deliberate use of exposed reinforced concrete, Brutalism emphasizes functionality and geometry in a distinctly visible manner. Masters like Le Corbusier laid the foundations of this movement with works that celebrated raw materiality and structural essentialism. Spreading worldwide, Brutalism took on various forms, from the strict European aesthetic to the dynamism of its manifestations in Brazil and India. Iconic examples of this movement include the Barbican Centre in London, Boston City Hall, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, all showcasing an imposing yet functionalist aesthetic.

But weren’t we supposed to be talking about Italy?

Exactly, I haven’t forgotten about the Bel Paese! In Italy, Brutalism has left an indelible mark thanks to the ingenuity of masters like Pier Luigi Nervi and Giuseppe Perugini. Consider, for instance, the Palazzo del Lavoro in Turin and the Palazzo dello Sport in Rome—these monuments are not just supports for complex and dynamic structures but true visual storytellers. They break with tradition and embrace a vision in which concrete is no longer just a material but a symbol of modernity and resilience.

At the same time, Italian Brutalist creations, while defying aesthetic conventions, often stand out with a certain dissonance in their surroundings, boldly and sometimes controversially distinguishing themselves within the urban and cultural fabric. These structures, often perceived as cold or alien, embody a critical chapter in Italy’s architectural history, elevating concrete from a mere structural element to a powerful tool of artistic and architectural expression. Their imposing forms and raw concrete surfaces invite reflection on their visual impact and their ability to influence and radically transform the urban landscape, sparking ongoing debates on their integration or contrast with the existing environment.

Paolo Castagna’s Contemporary Brutalism

The 2024 sculpture Zoe Brutalist Head by Paolo Castagna represents a remarkable example of how Brutalism, originally rooted in architecture, has found expression in art and design.

Castagna’s work builds an eloquent bridge between architectural and sculptural Brutalism, powerfully demonstrating how principles initially conceived for imposing structures can be reinterpreted in more personal and intimate works of art. In this transition from macro to micro, Castagna preserves the essence of solidity and authenticity that makes Brutalism such a provocative yet fascinating movement.

His choice to use concrete, the very symbol and pillar of Brutalism, is no coincidence: through this material, the artist explores and communicates a sense of strength and purity, transforming each sculpture into a tangible dialogue between creator and observer. Castagna boldly celebrates the beauty of imperfections and the expressive power of industrial materials, inviting viewers to rediscover the unique allure of surface irregularities.

Entrance to the temple (2023) Sculpture by Emmanuel Passeleu

Concrete: From Roman Architecture to Contemporary Sculpture

Suddenly, we find ourselves under the scorching sun of Rome, amidst a group of tourists captivated by the history and beauty of the monuments surrounding the Eternal City. Our guide, with an enthusiastic tone, leads us toward one of the most iconic buildings and begins to speak:

"The Pantheon, a true architectural gem of ancient Rome, stands in the Pigna district, at the heart of the historic center. Originally built as a temple dedicated to all deities, its history begins in 27 BCE when Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, son-in-law of Emperor Augustus, had it erected in honor of the goddess Cybele and other gods."

"Blah, blah, blah..."

"But do you know what the Pantheon is made of? It is primarily built with concrete!"

However, the concrete used by the ancient Romans, including that of the Pantheon, possesses unique characteristics that significantly differ from modern concrete. One of its key ingredients is pozzolana, a volcanic ash that, when mixed with lime and water, creates an extremely durable mortar. Pozzolana contains silica and alumina, which react with lime in the presence of water, forming hydraulic cementitious compounds that can harden even underwater, granting remarkable durability and resistance to structures.

Today, concrete is typically a mixture of Portland cement, sand, gravel, and water. Unlike pozzolana, modern cement requires firing at extremely high temperatures and lacks the hydraulic and self-healing properties of Roman concrete.

If the most enduring concrete of the past was almost exclusively used for architectural purposes, contemporary concrete has taken on a new role, becoming a younger and more expressive artistic language. Unlike traditional materials like marble or bronze, only in recent decades have many artists chosen it as a medium, drawn to its plasticity and materiality.

Past and Present in Emmanuel Passeleu’s Sculptural Work

A contemporary sculptural work that also recalls the historical connection between concrete and architecture is "Entrance to the Temple" (2023) by Emmanuel Passeleu. This sculpture combines essential architectural elements with a minimalist and visionary aesthetic, its form representing a section of an imaginary temple where staircases, arches, and openings evoke the pure and functional geometries of classical architecture. Concrete, with its raw and natural texture, becomes not only an expressive medium but also a conceptual bridge between past and present, evoking the solidity and timelessness of ancient constructions.

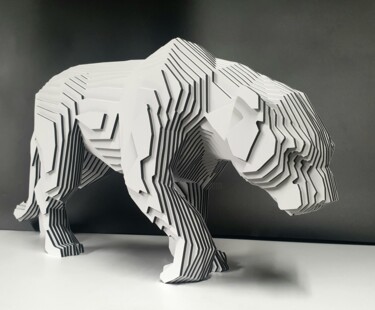

stroemender planet (2022) Sculpture by Nikolaus Weiler

stroemender planet (2022) Sculpture by Nikolaus Weiler

Aluminum Between Modernism, Pop Art, and Recycling

Aluminum is a relatively new material in art. While artists have used metals since ancient times, the one of our interest only became available after Hans Christian Ørsted first isolated it in the 1820s. However, it was not until the development of the Hall-Héroult process in 1886—which drastically lowered production costs—that aluminum became widely accessible for broader applications.

What was one of the first uses of aluminum in art?

The earliest known artistic use of aluminum dates back to 1893 with Anteros, a sculpture by Alfred Gilbert made entirely of aluminum. Located atop the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus, London, the work commemorated the Earl of Shaftesbury, a Victorian philanthropist, and became a symbol of technological innovation.

With its growing accessibility in the early 20th century, aluminum became a favored material in Modernism. In the 1930s, Alexander Calder began using thin sheets of aluminum for his famous mobiles, lightweight kinetic sculptures that move with air currents. He exploited the material’s lightness and flexibility to create works that seemed to defy gravity, introducing a new way to conceive the relationship between art and space.

In the 1960s, abstract sculptor Bill Barrett began using aluminum for large-scale works. His sculpture Hari IV, standing over 10 meters tall, welcomes students at the entrance of New Dorp High School in Staten Island, demonstrating how aluminum can be used to create monumental works that remain light and elegant.

Later, aluminum was no longer just considered a material but also a symbol of modernity, mass production, and consumerism. This made it irresistible to Pop artists, including James Rosenquist, who incorporated aluminum into his work The F-111.

Finally, it is crucial to highlight how aluminum, with its infinite recyclability, continues to inspire many artists who experiment with repurposing discarded objects to create ever-new works of art.

Contemporary Sculpture: Aluminum and Nikolaus Weiler’s Abstract Geometries

The sculpture Stroemender Planet (2022) by Nikolaus Weiler is an aluminum work distinguished by its strong visual and conceptual impact, characterized by a harmonious interaction between form, material, and dynamism.

The title suggests an idea of continuous movement, dynamism, and transformation—central themes in Weiler's artistic practice. The sculpture explores the concept of flow and change, possibly representing the life cycle, the constant evolution of energy, or the interconnectedness between natural and artificial elements.

The work combines aluminum and wood, two materials with contrasting characteristics that engage in a harmonious dialogue. Aluminum, with its polished finish and silver color, evokes modernity, lightness, and technology. In contrast, wood, with its warm and organic texture, recalls nature and tradition. The choice of materials underscores the tension between artificial and natural, rigid and fluid—fundamental elements in Weiler's artistic concept.

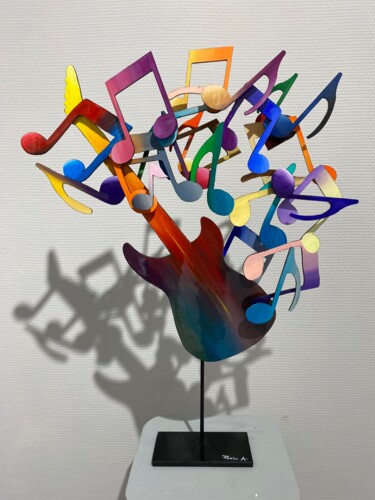

Buona'Pop-Art ! : L'imperatore Pop (2024) Sculpture by Achab

Buona'Pop-Art ! : L'imperatore Pop (2024) Sculpture by Achab

Plastic: A "New" Material for Art

Imagine walking through a museum, surrounded by contemporary sculptures. One of them captures your attention: a sinuous figure with fluid forms and vibrant colors that almost seem unnatural. You step closer, trying to guess the material it is made of. Marble? Glass? Resin? Then you read the label: plastic.

A material often considered mundane and ordinary, yet one that, in the hands of visionary artists, has become a tool of extraordinary creativity. Plastic has established itself as a fundamental presence in contemporary art, opening up new expressive possibilities and changing the way we perceive the relationship between art, materials, and our world.

Introduced in the second half of the 19th century with the invention of celluloid, plastic experienced a production boom during the 20th century, thanks to the discovery of synthetic materials such as PVC, polyethylene, and plexiglass. Its lightness, malleability, and ability to take on virtually any shape and color make it an extraordinarily versatile material, suitable for both monumental works and intricate sculptural details.

Unlike traditional materials like marble or bronze, plastic represents a break from the past. It is a symbol of technological progress and the contemporary era, yet it also carries a critical aspect: its environmental impact. This dual significance—innovation and ecological concern—makes it the perfect material for artists seeking to reflect on our time.

The Reinvention of Napoleon in Achab’s Pop Art

"Buona'Pop-Art! The Pop Emperor", a sculpture by Achab, is a bold and contemporary tribute, reinterpreting one of history’s most iconic figures in a minimalist, symbolic, and highly Pop-inspired manner. Who?

Napoleon Bonaparte!

The sculpture stands out for its geometric and stylized design. Napoleon’s face is reduced to an almost abstract essence, with angular shapes reminiscent of classical busts, yet radically simplified. The head is topped with his iconic black bicorne, an immediately recognizable symbol of the emperor, here represented in an essential and modernized form.

At the center of the piece, a massive red heart dominates the composition, positioned where a traditional bust would be. This choice of form and color suggests passion, power, and humanity, highlighting the emotional and symbolic dimension of the historical figure. The sculpture is completed by a dark blue base, providing visual stability and adding depth to the overall design.

The colors—black, white, red, and blue—are not random. They reflect a combination of strength, boldness, and modernity, utilizing a universal chromatic language that evokes the French flag while also resonating with Pop Art through its vibrancy and simplicity.

Iron age (2024) Sculpture by Roman Rabyk

Iron age (2024) Sculpture by Roman Rabyk

The Extraordinary Effects of Resin

At the end of the aforementioned museum journey, standing before the final exhibited work, the gaze settles on an unusual sculpture. Its surface appears glossy, almost liquid, with shapes that seem to float in space. Its transparency and chromatic nuances make it ambiguous—could it be glass or ceramic, perhaps even metal? Then, reading the label, one discovers that it is made of resin, a material that has increasingly found its place in contemporary art.

Resin is an organic substance, either natural or synthetic, that can solidify into a durable and resistant material through specific chemical processes. While in the past it was mainly used in industry or craftsmanship, today it has conquered the art world due to its versatility. Synthetic resins, such as epoxy, polyurethane, or polyester, offer limitless opportunities for experimentation.

Contemporary artists have chosen resin precisely for its ability to create extraordinary effects. With it, they can produce translucent and luminous works that refract light like glass or smooth, reflective surfaces reminiscent of polished metals. The ability to mix pigments and different materials provides an infinite range of shades and color play. Additionally, resin’s lightness and strength make it ideal for creating large-scale works without the weight and fragility associated with more traditional materials.

And What About Sustainability?

Since resin is predominantly synthetic, traditional versions may not be environmentally friendly. However, in recent years, research has developed new alternatives, such as bio-based resins or recycled materials, capable of reducing environmental impact without compromising artistic quality. More and more artists are adopting eco-friendly solutions, experimenting with new techniques to merge innovation with sustainability.

Roman Rabyk’s Resin Bust

The sculpture Iron Age by Roman Rabyk represents an emotional and symbolic journey through the dramatic events that have shaped contemporary Ukraine. Created with a combination of polyester resin, metal, acrylic, and varnish, the sculpture embodies a deep reflection on conflict, resilience, and national identity.

The bust depicts a human face marked by a network of textures and incisions, evoking wounds, scars, and fragments of recent history. The raw, metallic appearance of the surface intertwines with the transparency and layering of the resin, suggesting a sense of transformation and resilience. The choice of materials—a dialogue between the weight and solidity of metal and the flexibility of resin—symbolizes both inner strength and human fragility in the face of violence and change.

Finally, the sculpture seems to embody the transition from a metaphorical Iron Age to an era of renewal and reflection. The hardness of the metal represents the brutality and tension of reality, while the use of resin and varnish suggests the possibility of healing and transformation. The details of the face, emerging like relics of profound emotions, invite the viewer to contemplate the human experience in times of crisis.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli