Blue irises at dawn (2025) piece by Irina Laube

Blue irises at dawn (2025) piece by Irina Laube

Key Points

- Women erased from art history: Systemic barriers, not lack of talent, excluded them.

- Feminist art redefines the canon: Introduces new materials, bodies, and everyday life into art.

- Gender as performance: Artists challenge stereotypes and fixed identities.

- Art as activism: Feminist and queer art exposes injustice and sparks social change.

- AIDS crisis mobilized queer art: Art became a tool for protest, memory, and visibility.

- Queer art resists norms: Celebrates fluidity, nonconformity, and alternative identities.

- Intersectionality is key: Gender, race, class, and sexuality are explored together.

- ArtMajeur gives space to all voices: Highlighting women and LGBTQ+ creators worldwide.

Art and Feminism: From Marginalization to the Transformation of the Canon

For centuries, art history has been written by and for Western white men. Although women were present, they were systematically excluded—reduced to muses or amateurs, and rarely acknowledged as artists of equal merit. The provocative question posed by Linda Nochlin in 1971, “Why have there been no great women artists?”, sparked a conceptual revolution. Nochlin highlighted that the lack of recognition was not due to a lack of talent, but rather to social and institutional barriers: limited access to art education, prohibition from studying the nude from life, and exclusion from major exhibition venues and patronage networks.

In the 1980s, art historians such as Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker went further by criticizing the very language of the discipline. They analyzed terms like “Old Master” and “masterpiece,” and exposed the centrality of the nude female figure as an object of the male gaze in Western tradition. This was a notion already hinted at by John Berger in 1972 in his renowned book Ways of Seeing: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” In short, art reflects and reinforces existing social inequalities.

Myosotis (2025) piece by Emily Starck

Myosotis (2025) piece by Emily Starck

In the so-called first wave of feminist art, many artists fully embraced the female experience, expressing themselves through vaginal imagery, menstrual blood, nude self-portraits, and goddess symbols. Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–79) gave iconic form to this spirit: a collective monument to the erased history of women. At the same time, the use of "feminine" materials such as embroidery and sewing challenged the boundaries between high art and craft.

Over time, other artists rejected this essentialist celebration of femininity, choosing instead to explore the cultural constructs that define the very concept of “woman.” Gender was interpreted as a mask, a socially imposed performance. These artists deconstructed stereotypes and roles, revealing that female identity is a collection of learned poses rather than a natural essence.

Brown eyes (2025) piece by Ta Byrne

Brown eyes (2025) piece by Ta Byrne

Feminism exposed the sexist assumptions that permeated artistic institutions, questioning the very criteria of “greatness” and “genius.” Artists such as the aforementioned Judy Chicago, as well as Miriam Schapiro, Barbara Kruger, and Carolee Schneemann, redefined both the language and the spaces of art: Womanhouse, The Dinner Party, and the Guerrilla Girls’ posters openly challenged cultural patriarchy, reclaiming forgotten histories and envisioning new imaginaries.

The contribution of feminist artists was not limited to denunciation. Feminism also expanded expressive means: from performance to video art, from textile materials to the body itself as a medium. Feminist art demonstrated that the personal is political, that the everyday can be radical, and that the female body is a site of struggle and affirmation.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the approach became increasingly intersectional. Artists like Cindy Sherman, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas, and Shirin Aliabadi interwove issues of gender, race, class, and cultural identity. From this perspective, art is not just a mirror but a tool for political and social transformation.

my garden is better (2025) piece by Donatella Marraoni

my garden is better (2025) piece by Donatella Marraoni

Far from being a mere footnote, feminist art has redefined the very concept of art: who can make it, what it can be, and where it can happen. It has created new paradigms that continue to influence generations of artists, offering models of resistance, freedom, and complexity.

How does ArtMajeur respond to this perspective? By highlighting the work of women artists on the platform, selecting and promoting artworks that express a plurality of female visions—just like the images shown here.

But now it’s time to dive deeper into the relationship between art and the LGBT+ community!

Queer pray (2024) piece by Pauline Foucart

Queer pray (2024) piece by Pauline Foucart

Queer Art: Bodies, Desires, and New Forms of Visibility

Queer art is not a style or a genre, but a perspective that rejects imposed norms on identity, desire, and representation. Since the 1980s, with the reclaiming of the term "queer"—once a homophobic slur—by LGBT+ activists and artists, a new aesthetic has emerged that celebrates nonconformity, ambiguity, and fluidity.

Queer artists challenge dominant conventions on sexuality and gender, subverting the ordinary, giving voice to unauthorized desire, and creating new kinships and imaginaries. Far from a single identity, queer art shifts with context: it can be explicit or cryptic, celebrated or censored, recognized or criminalized.

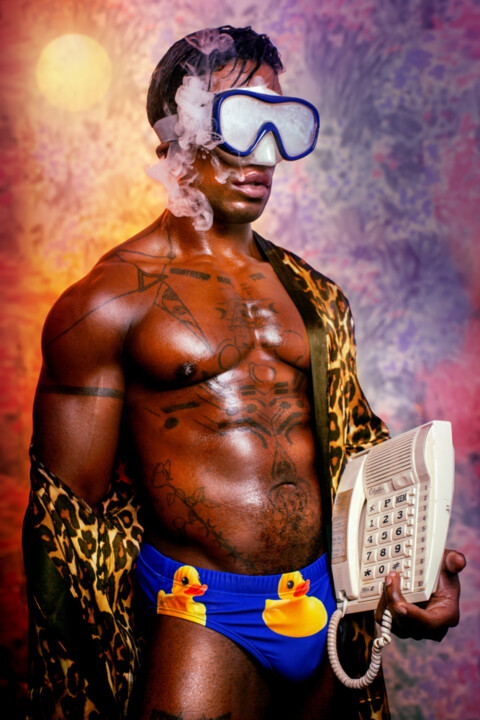

Guy with Color Spots #2 (2024) piece by Oleksandr Balbyshev

In its historical origins, queer art often emerged as a secret code, through veiled references to homosexual relationships in the works of artists such as Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg. During the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, queer art took on a highly political and activist role. Collectives like ACT UP, Gran Fury, and fierce pussy used protest imagery to denounce institutional inaction and demand visibility.

Artists like Keith Haring and Félix González-Torres transformed personal grief into public memory and social critique. Others, such as Nan Goldin and Isaac Julien, portrayed the everyday lives of queer communities, blending intimacy and resistance.

Queer art is also an archive and a rewriting of history. Exhibitions like Queer British Art 1861–1967 have recovered invisible figures such as Simeon Solomon and Claude Cahun, recognizing a queer tradition that predates modern identity categories.

prjp \ A man. Hidden man - {$M} (2019) piece by Leni Smoragdova

prjp \ A man. Hidden man - {$M} (2019) piece by Leni Smoragdova

In the new millennium, queer art has become increasingly intersectional: artists like Zanele Muholi, Cassils, Wu Tsang, and Juliana Huxtable intertwine gender, race, class, and origin to convey complex and plural experiences. The queer body becomes not only a subject but also a medium, a performance, a space of affirmation.

Public space has also been reclaimed: from the mural posters of the 1980s to the monumental AIDS Memorial Quilt, queer art has occupied streets, squares, and museums—challenging heteronormativity with irony, pain, sensuality, and pride.

Today, queer art continues to expand its boundaries, blending languages and cultures. It is not a label but a process, a practice of resistance and transformation that centers the free expression of desire, identity, and memory.

L'ENNUI DES RICHES (2024) piece by Romain Berger

L'ENNUI DES RICHES (2024) piece by Romain Berger

But after all, are we really sure that Queer Art only emerged starting in the 1980s?

Here's a reflection for you: traces of queer identity can be found well before the contemporary era. In European prehistoric cave art, some scholars have identified phallic symbols and depictions potentially linked to homosexual erotic rituals. The Egyptian tomb of the officials Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep—shown holding hands and embracing like a married couple—stands as one of the rare ancient iconographic examples of a possible relationship between two men. In Ancient Greece as well, homosexual eroticism was depicted quite openly, especially in educational and military contexts, as seen in the famed “Sacred Band” of Thebes, made up of male lover pairs.

These representations should not be interpreted through modern identity labels like "gay" or "lesbian," but they show that homosexuality has long been an integral—and visible—part of art history and visual culture. These works do not just reflect the aesthetics of queer desire, but also its presence, resilience, and ability to exist even in times when society remained silent or condemning.

Finally, once again, ArtMajeur embraces this perspective by showcasing works that address queer themes, offering visibility and space to voices that challenge conventions and expand the boundaries of contemporary art.

FAQ

1. Why were women excluded from art history for so long?

Because institutional structures limited their access to training, patronage, and exhibitions. The canon was built by men, for men — marginalizing women's artistic achievements.

2. What was the significance of Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay?

Her essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, reframed the question: it wasn’t about talent, but systemic exclusion. It sparked the feminist re-reading of art history.

3. How has feminist art influenced today’s art world?

It expanded the definition of art to include video, performance, textiles, and the body. It also made space for political, emotional, and domestic themes that had been dismissed.

4. What exactly is “queer art”?

Queer art explores identity, desire, and gender beyond societal norms. It is fluid, defiant, and often intersectional — not tied to a fixed aesthetic but rooted in freedom and visibility.

5. How did queer art respond to the AIDS crisis?

Artists and activist collectives used art to challenge silence and stigma, turning mourning into protest. Their work fused public health messaging with emotional expression and political urgency.

6. Can queer and feminist art overlap?

Absolutely. Many artists engage with both feminist and queer themes, challenging binary notions of gender, exposing stereotypes, and creating inclusive spaces for expression.

7. How do platforms like ArtMajeur support this kind of work?

By promoting artworks from women and LGBTQ+ artists, and giving visibility to diverse voices that challenge conventions, represent underrepresented identities, and reimagine what art can be.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli