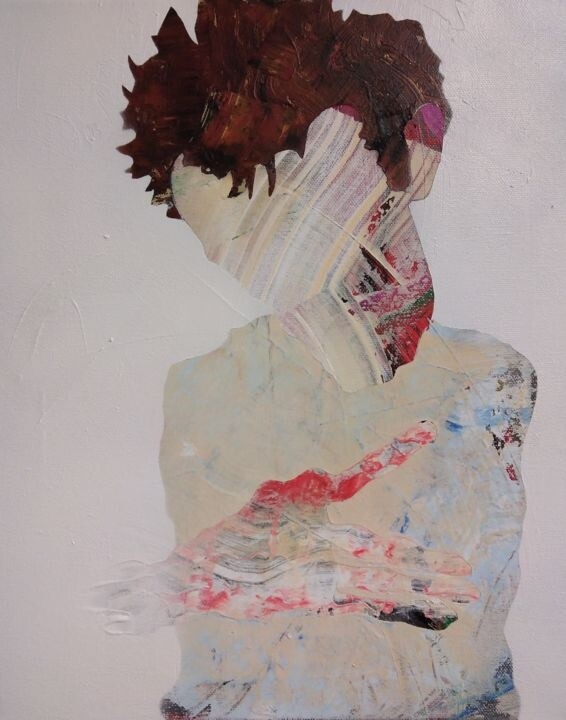

Evgen Semenyuk, Egon Schiele style man in white mask, 2020. Oil / acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 cm.

Evgen Semenyuk, Egon Schiele style man in white mask, 2020. Oil / acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 cm.

"Art cannot be modern. Art is primordially eternal."

With the words of Egon Schiele, the iconic Austrian painter and printmaker born in 1890, a fundamental concept of art history is introduced, aimed at demonstrating how masterpieces of all times turn out to be outside an actual and limited space-time dimension, finding their place in a place, which, similar to an eternal and continuous present, recognizes them as objects to be contemplated endlessly, in order to remember, demonstrate and exalt the highest capacities of humankind. In this narrative without "deadlines," we cannot help but mention the self-portraits of the aforementioned master, which have gone down in history, both as a tool of highly expressionistic figurative investigation and as a means through which to explicate and make known the artist's temperament, captured during different stages of his career. In fact, Schiele's numerous self-portraits, executed in the years between 1910 and 1918, represent an authentic exploration of the aforementioned man's state of mind, allowing us to enter "into the confidence" of one of the best-known painters of the 20th century. Therefore, in order to get to know, both the work and the artist, it is good to start with the year 1910, the date of execution of three masterpieces of the aforementioned genre: Self-Portrait with striped shirt, Self-Portrait Pulling Down an Eyelid and Self-portrait standing. In the first watercolor drawing, a Schiele in his early twenties presents himself to the viewer wearing a striped shirt, even though, through his intense and engaging gaze, he might appear as "naked," as his eyes reveal to us his deeper, highly rebellious, inquisitive and spiritual essence. From a chromatic point of view, however, the hues of the clothes are repeated in those of the protagonist's head, making the composition harmonious, both compositionally and chromatically. Speaking of Self-Portrait Pulling Down an Eyelid, the work, which again reveals Schiele's nurtured interest in the self-portrait, a figurative tendency considered quite unusual at the time, presents a marked departure from the stylistic features of Klimt's previously reigning work. In fact, the aforementioned watercolor, while repurposing vibrant and decorative colors derived from the Baumgarten master, introduces a new expressive body language aimed at suggesting the weight of the effigy's thoughts and feelings, often focused on concerns related to the themes of death, love, sex and the process of becoming an artist. Also from the same year, Self-portrait standing represents the pinnacle of Schiele's introspective turn, a tendency that is expressed in a highly dramatic, raw and radical way by the very grimace of pain in which the artist has immortalized himself, pursuing the goal of revealing a more authentic and painful viewpoint on life, now definitively far removed from the sumptuous and glittering gold of Klimtian derivation. Such phatos can also be seen in a later watercolor, namely the Self-Portrait attributable to 1911, in which the artist appears in a similar pose and attitude.

Gabriele Donelli, Portrait of Egon Schiele, 2009. Acrylic on cardboard, 62 x 46 cm.

Gabriele Donelli, Portrait of Egon Schiele, 2009. Acrylic on cardboard, 62 x 46 cm.

Emily Starck, Egon Schiele, 2020. Acrylic / watercolor / graphite / oil / collage on paper, 65 x 50 cm.

Emily Starck, Egon Schiele, 2020. Acrylic / watercolor / graphite / oil / collage on paper, 65 x 50 cm.

As for 1912, it is impossible not to mention Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant, one of the Austrian artist's most admired works, which, aimed at capturing Schiele's image from an unprecedented perspective, crushes the protagonist into an innovative horizontal format. In addition, the tension inherent in the effigy is also heightened by the position assumed by his head, which, facing to the right, "irecedes" from his eyes, which are intent on staring at the viewer looking in the opposite direction. In such an emotionally charged context, the artist's shoulders stand out forcefully against the light background, enriched by the presence of the twig with leaves and the Chinese lanterns. Finally, still on the subject of color, it is important not to overlook the rich chromaticism of the skin and the eye, which, having a red pupil, reveals a soul out of the ordinary in sensitivity and artistic sense. Summing up the creative impetus of 1915 is an iconic work by the master, namely Death and the Maiden, a canvas in which Schiele wants to express all the sadness he felt at abandoning his model and lover Wally. Indeed, the masterpiece depicts the two lovers, who, portrayed in the act of embracing each other, are arranged on a crumpled sheet, placed against a rocky background, intended to allude, with its geometries, to the interlocking bodies of the effigies. Precisely such physical proximity is not meant to refer to an actual amorous ecstasy, but to an attitude that precedes detachment, crystallized in the improbable postures, which refer to a tangible sense of restlessness, precariousness and death. The epilogue of such feeling is also confirmed by the distant gazes of the effigies, as the woman is intent on looking outward, as if lost in thought, while her companion, with eyes wide open in nothingness, even seems to be lost in his complicated inner world. Referring to Schiele's life, however, the end of the aforementioned feeling was not due to a simple exhaustion of love, as the artist left Wally only to obtain an advantageous marriage with a more socially presentable woman. Therefore, it emerges how even in the more passionate and instinctive world of Schiele's art, on some occasions, rationality and calculation took over from the more authentic passion.

Gaspard De Gouges, Gustavia and friends, 1999. Oil / acrylic / charcoal on MDF panel, 157 x 104 cm.

Gaspard De Gouges, Gustavia and friends, 1999. Oil / acrylic / charcoal on MDF panel, 157 x 104 cm.

Walter Diem, Bild 21 120 sammlung diem, 2021. Painting, chalk / watercolor on paper, 70 x 50 cm.

Schiele's life: the tale continues in Artmajeur's artworks

Schiele's work fine-tuned an expressive approach distinguished by contorted figures and "sharp" brushstrokes that, extremely charged with emotional energy, are to this day a powerful symbol of psychological, emotional and sexual expression. In fact, Artmajeur's collection of artworks is rich, both in viewpoints inspired by the Viennese master's figurative investigation and in actual "remakes" of his greatest masterpieces, paintings through which it is possible to continue the narrative about the artist's life, such as Julianne Moore plays Schiele by Francesco Dezio, Embrace by Dmitriy Trubin and After Egon Schiele by Sebastien Montag.

Francesco Dezio, Julianne Moore plays Schiele, 2022. Watercolor on paper, 56 x 45 cm.

Francesco Dezio, Julianne Moore plays Schiele, 2022. Watercolor on paper, 56 x 45 cm.

Francesco Dezio: Julianne Moore interprets Schiele

Dezio's watercolor on paper represents the "third generation" of a great masterpiece of art history, as the Italian artist has reinterpreted the well-known photograph by Peter Lindbergh, who, in turn, made current Schiele's masterpiece entitled Seated Woman with a Bent Knee (1917). Indeed, in the German photographer's shot, Wally, Schiele's aforementioned lover and model, takes on the likeness of the popular American actress Julianne Moore, who, in the same context, has also impersonated the protagonists of other well-known works of art, such as: Gustav Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), John Currin's The Cripple (1997), Edgar Degas' Little Dancer of Fourteen (1879-1881), and Amedeo Modigliani's Portrait of Lunia Czechowska with Fan (1919). Returning instead to the German master's masterpiece, from which, both Dezio and Lindbergh took their cues, it depicts Wally in an informal pose, who, with her gaze turned toward the viewer, assumes a highly expressive, casual and erotic attitude. However, behind the security of Woman sitting with a bent knee lies the artist's innermost longing, who though married to another woman, continues to revive his thwarted love within the dimension of the canvas.

Dmitriy Trubin, Embrace. Painted, dimensions available upon request.

Dmitriy Trubin, Embrace. Painted, dimensions available upon request.

Dmitriy Trubin: Embrace

Trubin's painting represents an original and personal reinterpretation of Schiele's Embrace, a masterpiece dated 1917, in which the artist depicted himself entwined in passionate intercourse with his wife Edith Harms, whom he married in 1915. Thus, the composition is imbued with a strong sentimentality, which, characteristic of the works created after the master's marriage, made his work less tormented than usual. Nevertheless, a veiled semblance of sorrowful melancholy remains palpable, a sentiment probably premonitory of the ominous events of 1918, the year in which the Spanish flu, in addition to millions of victims, also took Edith away. Regarding Trubin's interpretation of the Embrace, it maintains the iconic voyeuristic point of view of the original, according to which the viewer insinuates himself inside the private sphere of a young couple, now transformed into two specimens of mannequins worthy of Giorgio de Chirico's brush. The latter himself, starting in 1915, populated his paintings with monumental figures that, mysteriously devoid of eyes, mouth and ears, alluded, probably, to the ability to investigate reality even beyond its phenomenal appearance. In addition, it is also possible to interpret the Italian master's mannequins as symbols of extremely melancholy state of mind, a mood that can certainly be linked to Schiele's veiled pessimism.

Sebastien Montag, After Egon Schiele, 2021. Acrylic, spray paint on canvas, 41 x 33 cm.

Sebastien Montag, After Egon Schiele, 2021. Acrylic, spray paint on canvas, 41 x 33 cm.

Sebastien Montag: After Egon Schiele

After Egon Schiele is a "mute" and "minimalist" reinterpretation of Self Portrait with Lowered, in that, in the Artmajeur artist's "remake," the intense gaze of Schiele's masterpiece has been "erased," along with the character's other distinctive features. Probably, this new point of view was inspired by contemporaneity, that is, by a reality in which, compared to the past, we tend to be more rapid, direct and synthetic, also thanks to the forma mentis transmitted to us by new technologies. Returning to Self Portrait with Lowered Head, on the other hand, the artwork is characterized by the fact that it immortalizes Schiele with his head bent, a position that emphasizes the character's upward gaze, aimed at assuming an extremely grotesque and disturbing attitude. In addition, another important detail in the painting is the large left hand, which, with its fingers spread apart, repeats the same pose as in The Hermits and another self-portrait from the same year. In reality, however, the hands turn out to be a "must" in Schiele's artistic production in general, since they are also the protagonists of the numerous photographs, which immortalize the master. Probably, they are symbolic of a defensive attitude toward life and the world, which the artist assumes by putting them before everything that comes his way.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli