Still lifes are an exercise as fascinating as it is enigmatic for artists. Fascinating by the technique, because many painters have "made their hand" on these genre paintings, easy to realize because they don't require models, no long hours of poses, but also because they can be painted directly in the studio, often even by candlelight.

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers (F456), 1888. Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

Above all, many still lifes turn out to be particularly mysterious, because they contain deeper meanings than a simple representation of inanimate objects. Although often forgotten, still lifes are the legacy of the vanitas, those genre paintings that remind us of the inevitable passing of time and the perishable nature of the things we love. In painting, a damaged fruit can illustrate a death, and a blooming sunflower can represent melancholy.

So, what are the most famous still lifes in art history?

1. Fede Galizia, Still Life (ca. 1610)

Fede Galizia, Still Life, circa 1610. Private collection.

What if we started by putting some justice back into the history of Art? It might come as a surprise, considering the place left to women in the artistic epic of the last few centuries, but the emergence of the still life as a distinctive style is mainly the result of a fierce female will.

A woman? No, women. It was at the beginning of the 17th century that the first real experiments with still lifes flourished, in the modern sense of the term (far from the old vanities), meaning compositions of inanimate objects, generally fruit, foodstuffs, utensils and animals.

Fede Galizia, Still life with apples on a majolica tazza, with medlars and white currants, ca. 1612. Unknown Localisation.

At that time, still lifes weren't depreciated but coexisted with other traditional genres: mythological and religious paintings, portraits, or landscapes. However, painters mainly painted portraits (because they were paid for it), then mythological and religious paintings (because it made them famous), and gradually abandoned vanities, still lifes and landscapes which brought them neither fame nor fortune. Europe is in full artistic effervescence, from the Netherlands to Italy, through France, many artistic places are bubbling with talent of all kinds. Among these artists, three women will detach themselves from the common sense to devote most of their creativity to the realization of still lifes.

But who are these Powerpuff Girls of Still Lifes?

First, in Milan (Italy), Fede Galizia creates series of delicious fruit baskets. A few thousand kilometers away, one of her contemporaries, Clara Peeters, living in Antwerp (Netherlands), blossoms through hundreds of still lifes representing tables set for copious and refined meals. Finally, a few years later, around 1630, the French artist Louise Moillon also produced numerous still lifes in the vein of Fede Galizia.

Clara Peeters, Still life with silver-gilt tazza, 1613. Private collection.

These three women undeniably popularized this genre throughout Europe, both with collectors and other artists. However, it’s their male counterparts, who arrived later, who are given a place of choice in the history of Art. Let us do justice today to these three women who have been unjustly forgotten despite their pioneering work, which deserves to be rediscovered.

Louise Moillon, Still Life with Basket of Fruit and Asparagus, 1630. Art Institute of Chicago.

If the rehabilitation of women artists in the history of Art is a subject that is close to your heart, check out our dedicated articles: 4 Extraordinarily Badass Women Who Changed the (very patriarchal) History of Art and 4 Women Artists Overshadowed by their Husband's Fame.

2. Jean-Siméon Chardin, The Ray (1728)

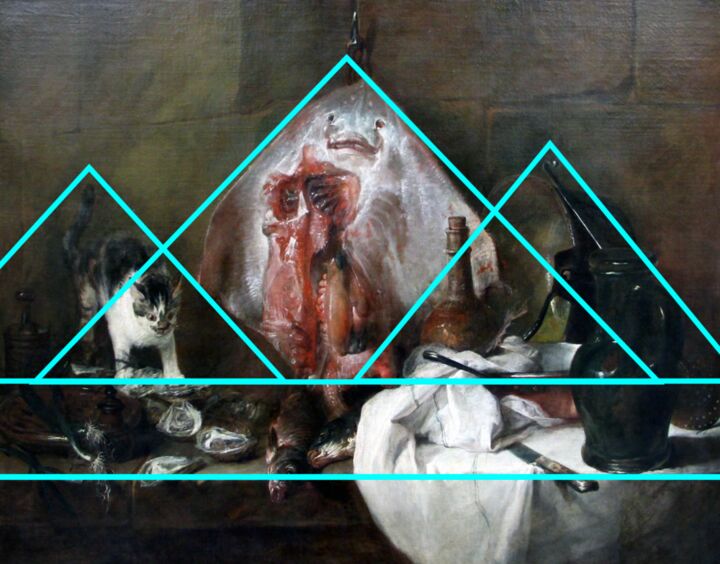

Jean Siméon Chardin, The Ray, 1728. Louvre Museum, Paris.

For his contemporaries, Jean-Siméon Chardin was considered an absolute master of the genre, notably for his technical skill and astonishing compositions. This artwork, on display in the Louvre Museum, is a compelling testament to his painterly efficiency.

In this composition, we discover a small wooden workbench on which various objects are arranged: kitchen utensils and containers find their place alongside a cat, fish carcasses and oysters. Above this strange disorder, a brick wall imposes its half-light and a ray, in the center of the artwork, is maintained by a metal hook.

Why such a mess? This tangle of inanimate objects (apart from this intrepid feline) allows the artist to express his pictorial will more freely: here, for example, he chooses a pyramidal construction to structure the composition. The central pyramid is obviously represented by the ray, then two other lower pyramids are revealed on each side of the animal: one takes its summit at the end of the feline's tail, the other on the end of the ladle placed in balance on the cast iron pot.

The white tablecloth creates a duality in the center of the artwork and divides the composition in two. Finally, the visible entrails of the ray bring a surprising brutality to the artwork: arranged like this, its strange facial expression faces us and makes us uncomfortable. Chardin takes us far from romanticism with this disembowelled stingray, which is as sinister as it is disturbing.

3. Edouard Manet, Bunch of Asparagus and The Asparagus (1880)

Edouard Manet, Bunch of Asparagus, 1880. Wallraf–Richartz Museum, Cologne, Germany.

Here's an unconventional story in the art world, and a funny anecdote to shine in society. These two still lifes are one and the same and are better known for the story behind their creation than for their pure aesthetic qualities.

Once upon a time, in 1880, there was an art collector and good friend of the Impressionists: Charles Ephrussi. He decided to commission his favorite artist, Edouard Manet, to paint a still life representing a bunch of asparagus. He offered him 800 francs for the artwork. Manet accepted, painted the asparagus, and sent the result to his patron. After receiving it, it's an astonishment: Charles Ephrussi loves the painting, he was delighted by this magnificent bunch of asparagus and gives 1000 francs to Manet (so, 200 francs more than expected). The artist then decided to offer this generous patron another still life - The Asparagus - accompanied by the following comment: "There was one missing from your bunch.”.

Edouard Manet, A Sprig of Asparagus, 1880. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

This was all it took for an apparently insignificant artwork to become a legend in the history of Modern Art. Today, the two artworks are separated: one is in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the other in the City Museum of Cologne, but because they're both so closely related, we hope with all our hearts that they will one day come together.

4. Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Skull (ca. 1898)

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Skull, circa 1898. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

How can we talk about the most famous still lifes in the history of art without mentioning the undisputed master of this stylistic exercise: the strange and fascinating Paul Cézanne. This artist, in love with the South of France, realized several hundreds of still lifes throughout his career, all more sublime the ones than the others.

For Wassily Kandinsky, Cézanne "elevated still life to such a point that it ceased to be inanimate. He painted these things as human beings because he had received the ability to guess the inner life of everything". A beautiful homage for this passionate painter, who applied himself to analyze the painting under the prism of mathematics.

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples, ca. 1892. Art Institute of Chicago.

If Cézanne's apples are so bewitching, it's because he saw them as spheres and cylinders, and not as simple objects to represent. If his compositions are so natural, it’s because they aren’t made from lines and shapes, but by the alchemy of contrasts. The form is created by means of an exact concordance of tones, and if this coordination is harmonious, then the painting makes itself. In the language of artists, "modeling" means above all "modulating". Cézanne's work is an essential part of the history of art, foreshadowing the major artistic trends of the 20th century, notably Cubism.

5. Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick (1910)

Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick, 1910. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

It was with Pablo Picasso that Georges Braque co-founded Cubism, the dominant artistic style of the twentieth century. Cubism is an artistic movement that is characterized mainly by the abandonment of classical perspective, the breakup of forms into different geometric facets (which gives the impression of "cubes") and the independence of the different planes of the composition. To make sense of their research, Braque and Picasso had to produce artwork according to these processes: Braque first made landscapes, then he set about deconstructing the traditional theme of still life.

Violin and Candlestick is certainly the most famous cubist still life in the History of Art. Created in 1910, it is part of the first phase of Cubism, commonly known as Analytical Cubism. Here, the elements of the composition are represented by simple shapes, using multiple points of view in a purely monochromatic style: the artist used only the different tones of the same color. With Braque and Picasso, art becomes a logical and mathematical exercise.

Georges Braque, Still Life with Glass and Letters, 1914. MoMA, New York.

And that's it, this classification is over, and we hope you enjoyed it!

To go further, you can read our article on most famous self-portraits here, or discover our Still Lifes Collection, available on Artmajeur here.

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)