Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Three Puppies, 1888. Oil on wood, 91.8 x 62.6 cm. Moma.

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Three Puppies, 1888. Oil on wood, 91.8 x 62.6 cm. Moma.

The genre of still life: let's dive right in!

Let's get straight to the point: when you read about still life on the web, you'll be able to find examples from Hellenistic, Roman, Medieval, and Renaissance periods. They are characterized by the predominant depiction of inanimate subjects, both natural and artificial. Despite these being the defining features of this type of composition, it officially became a distinct genre, recognized, specialized, and valued, only by the end of the 16th century. The story continues with significant popularity and dissemination in the following century, although in the 18th century, still life was relegated to the bottom of the hierarchical ranking of figurative art types. Nevertheless, the progressive notoriety acquired by the genre is primarily attributed to the Flemish example between the 16th and 17th centuries, a context in which the term "stilleven" was coined, which literally means "still life." While the latter meaning has been retained in the English languages, the same is not true in the Neo-Latin languages, where the word immobile has been replaced with dead (e.g., "natura morta"). This change resulted from an Italian reinterpretation of the term, which took place in the late 18th century, probably due to a simple translation error, altering the older Dutch phrase. At this point, the narrative continues in my ranking, demonstrating the success of a genre often underestimated but indeed addressed by immortal masters from every artistic movement, trend, and current.

Caravaggio, Basket of fruit, 1597-1600. Oil on canvas, 46×64 cm. Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

Caravaggio, Basket of fruit, 1597-1600. Oil on canvas, 46×64 cm. Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

1.Caravaggio: Basket of Fruit (1600)

Let's start with one of the most famous works in the history of art, belonging to the "unfortunate" genre of still life. I am referring, to begin with an adrenaline rush and a tendency towards Stendhal's syndrome, to Caravaggio's Basket of Fruit, a masterpiece dating back to 1600. The painting is important both from a historical-artistic point of view and in terms of subject matter. It is not only one of the earliest examples of the still life artistic genre but also represents, in keeping with the Italian aesthetic of realism, not only immaculate fruit but also a rotten apple and leaves that are dry and riddled with holes from insects. All of this was conceived by the master to allude to the precariousness of human existence but also to celebrate the authentic imperfection of nature. This includes a woven wicker basket, which, at the center of the composition, holds clusters of grapes, pears, apples, figs, and peaches, resting on a wooden surface that runs parallel to the viewer's gaze. The viewer can only focus on the realism of the subject, which is actually denied by the presence of some details. In fact, have you noticed that, quite unbelievably, the painter accomplished the impossible mission of placing fruits from different seasons side by side? Finally, I also want to justify Caravaggio's choice of subject, who, in a late mannerist context, felt justified in expressing his interest in nature, often previously used as a mere background element in portraiture or religious themes.

Rembrandt, Slaughtered Ox, 1655. Oil on panel. 95.5 x 68.8 cm. Louvre, Paris.

Rembrandt, Slaughtered Ox, 1655. Oil on panel. 95.5 x 68.8 cm. Louvre, Paris.

2.Rembrandt: Slaughtered Ox (1655)

We continue with the tachycardia, dizziness, confusion and hallucinations of the Stendhal syndrome, as we approach a masterpiece rich in symbolic meanings, aimed at testifying to how between the 16th and 17th centuries still life compositions triumphed, among them, those in which animal carcasses appeared, to be understood as mournful and direct memento mori, also capable of exercising artists, who approached the complexity of form and color. However, Rembrandt's Slaughtered Ox, a masterpiece depicting the quartered carcass of an animal suspended by its two hind legs, which are tied to a wooden beam, also reminds us of the famous example of the Crucifixion of Jesus. Now we have reached a critical moment in the description, as the work actually represents a false still life. In fact, the presence of a woman in the background, who appears behind a half-open door, turns the painting into a genre painting, all intent on depicting a scene of everyday life.

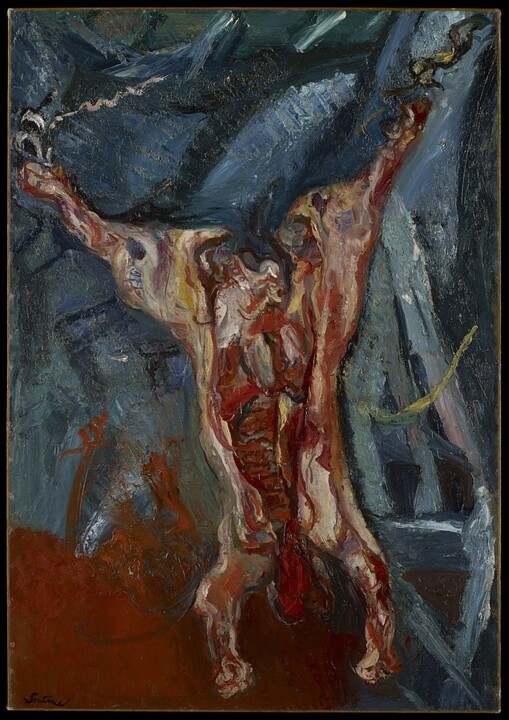

Chaim Soutine, Beef Carcass, 1925. Oil on canvas, 147.32 x 113.03 cm. Minneapolis Institute of Art Collection.

Chaim Soutine, Beef Carcass, 1925. Oil on canvas, 147.32 x 113.03 cm. Minneapolis Institute of Art Collection.

3.Chaim Soutine: Beef Carcass (1925)

To transform the above into a true still life, Chaim Soutine came to the rescue! I am referring to his Beef Carcass from 1925, actually inspired by the masterpiece described above, which was reinterpreted in a series of works with the same subject by the Russian master. It is worth noting, however, that other great masters, including Daumier and Slevogt, approached the same theme, although in Soutine's case, an especially emotional interpretation is evident, characterized by intense and saturated colors that reflect the painter's eccentric personality. Let me briefly dwell on this characteristic aspect of the artist to reveal some grim details about his execution of the animal still lifes in question. Soutine, friends with the employees of a Parisian slaughterhouse, would purchase meat from them and take it to his studio to paint for weeks, during which time it would also undergo malodorous decomposition... We do not know whether this fixation on the animal world stemmed from an initial deprivation, as it is known that the artist, when he was still poor, avoided buying meat because it was too expensive. Paradoxically, once he became wealthy, he decided to purchase it only to study and paint it...

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. Oil on canvas, 92.2 cm × 73 cm. National Gallery, London.

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. Oil on canvas, 92.2 cm × 73 cm. National Gallery, London.

4.Vincent van Gogh: Sunflowers (1888)

The viewer's gaze is fixed on the sole subject depicted in the still life in question: a bouquet of sunflowers arranged in a vase, their forms resting on a yellow surface, ready to stand out against a light-colored wall. The sunflowers, harvested at various stages of ripeness, appear similarly in a series of seven works by the artist, conceived to decorate the room in Arles that van Gogh had intended for his friend and colleague, Gauguin. Let me pause for a moment on the word "friend," revealing that, in reality, the French artist reached out to Vincent only after being financially compensated by Theo van Gogh. But why was there a need for money? Well, let's say that Gauguin already imagined that living with Vincent would be a bit problematic, and he also disliked the aforementioned Mediterranean province. In any case, Paul got rid of his friend shortly thereafter, following one of the most famous disputes in art history, leaving Arles and triggering a self-harming crisis in van Gogh, culminating in the now tragic and iconic ear-cutting incident. Returning to the flowers, the sunflowers in the various compositions are also known to vary in number, ranging from fourteen to fifteen specimens. Why this particular choice? Vincent held the number 14 dear because it referred to the number of apostles, while with 15, he included himself within the same reference (14 apostles + Vincent). Irony: this top ten talks about events that are better left untried at home!

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Three Puppies, 1888. Oil on wood, 91.8 x 62.6 cm. Moma.

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Three Puppies, 1888. Oil on wood, 91.8 x 62.6 cm. Moma.

5.Paul Gauguin: Still Life with Three Puppies (1888)

As the animal activist that I am, I had to make up for the presence, within this top 10, of deceased living beings, a purpose that I fulfill by talking about Gauguin's Still life with three puppies, a work, which, at the same time, raises my doubts. In fact, if we are talking about still life, how, in fact, could the animals even be alive? If we are to be faithful to the assumptions of the genre, the painted fauna should actually be dead and, the living ones, would be acceptable only if made from deceased models. We do know, however, that in the figurative context in which Gauguin found himself working, he was now quite free from this kind of older limitation, so much so that at the time of the making of Still life with three puppies, he was living in Brittany together with a group of experimental artists. It was precisely with the latter that he moved away from the more realistic representations, resulting, on some occasions, in stylistic features with a partially abstract flavor, the result of the union he advocated between dream and nature. In any case, a decisive component of the masterpiece is also the peculiar interpretation of the stylistic features of Japanese art, found, for example, in the delineation in blue of the puppies' bodies, as well as in the motif of their coats, intended to recall that of the tablecloth print.

Paul Cezanne, Still Life with Apples and Oranges, 1899. Oil on canvas, 74×93 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Paul Cezanne, Still Life with Apples and Oranges, 1899. Oil on canvas, 74×93 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

6.Paul Cezanne: Still Life with Apples and Oranges (1899)

Here we are, describing another one of the most popular works in the genre: why did I say what I said? Well, it's important to know that in Still Life with Apples and Oranges, many art historians have recognized a precursor to Cubism, as it employs geometric shapes to represent the fruits, along with the presence of broken lines in the folds of the fabric. Let's now describe what was anticipated: on a canvas, several apples and oranges are arranged, some scattered, some gathered on plates, which, on the right side of the support, are also accompanied by the presence of a pitcher. The aforementioned canvas rests on a floral fabric, meant to highlight the presence of complementary blue and orange colors. Let's now delve into this chromatic aspect of the masterpiece, entirely focused on describing its objects using tonal variations, which, in the case of the fruit, range from yellow to red. The view of these colors is not offered from a perspective that adheres to geometric rules, as the space is the result of the overlapping of very simple volumes, seen from an elevated viewpoint.

Frida Kahlo, Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954. Frida Kahlo Museum. @danielharoro

7.Frida Kahlo: Viva la Vida, Watermelons (1954)

The importance and iconicity of the work in question will be revealed in the course of the narrative, but for now, I want to give you a preview by telling you that I chose this painting to demonstrate the potential of the still life genre, which is equally capable of conveying highly positive and hopeful messages. However, what I just mentioned arises from a strong contrast, a recurring element in Frida's work. In this case, the duality is due to the fact that the artist painted the masterpiece in a grave state of health, yet she depicted watermelons, the quintessential symbol of the vivacity of life. When we closely observe these subjects, however, we notice that they are undergoing different stages of ripening, most likely alluding to the different stages of human life. In any case, optimism spreads from the use of red, combined with the green complementary color of the fruit's rind, a chromatic aspect that creates a pleasing and vibrant contrast. Finally, the painter's intentions, until then only speculated, become clear in the lower watermelon, which bears the phrase: "Viva la Vida - Coyoacán 1954 Mexico." As the narration about the painting concludes, so does the one about Frida, as Viva la Vida is, in all respects, the last work the artist created...

Salvador Dalí, Living Still Life, 1956. Oil on canvas, 125 cm × 160 cm. Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida.@

artpreciatetheday

8.Salvador Dalí: Living Still Life (1956)

In contrast, the strange dynamism-dead nature association occurs in Salvador Dali's Living Still Life, a 1956 masterpiece made during the period that the Catalan called Nuclear Mysticism, a painterly moment in which he sought to investigate about the relationship between the conscious mind and quantum physics. How can I try to explain the above in a simple way? Well, Dali, in making the masterpiece in question, was inspired, by appealing to his conscious mind, by recalling the example of Van Schooten, rendered by his still life Table with Food. Speaking of physics, it came into play when the master transformed the Dutch table setting, giving it the miracle of movement, to be interpreted, of course, in perfect surrealist fashion. Consequently, the generally static still life genre becomes, as per the title, living! Existence is, in this specific case, witnessed by the motion of the objects, reducible, in their smallest component, to atomic particles. Through the latter we arrive at the generative concept of the painting, the aforementioned Nuclear Mysticism, idissolubly inspired by the nefarious and terrifying atomic bomb dropped by the United States on Japan.

Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 51 cm × 41 cm. Museum of Modern Art.

9.Andy Warhol: Campbell's Soup Cans (1962)

The 32 identical silk screen prints, inspired by the Campbell's soup packaging, intentionally repeat the subject in question, aiming to create an installation that reproduces the typical serial arrangement of supermarket products. The theme, interpreted multiple times by the artist, was first rendered in the masterpiece in question, which was also conceived to allude to the constant presence of soup in the lives of Americans at that time. Just think that Andy himself, once the work was completed, confessed to having eaten the product repeatedly for twenty years! Furthermore, through the omnipresence of the image in question, he also challenged the idea of painting as a means of invention and originality because the serial nature of Campbell's Soup Cans is due to the use of a semi-mechanized screen printing technique. However, there is an inaccuracy in all that I have written: can you find it? Just kidding, but I want to clarify that the soup cans are not, as announced above, identical to each other because each painting represents a replica of an original model with some distinctive details applied. At this point, did Andy unintentionally highlight those particular characteristics that make even industrial objects unique?

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life, 1949. Private collection.

10.Giorgio Morandi: Still Life (1950)

Several household objects are grouped almost in the center of the painting, where they rest on an indefinite surface, standing out against a background of similar but lighter hues. What is the reason for the choice to immortalize a few simply arranged objects? To answer, we must go back to the 1940s and 1950s, a period in which the painter opted for this type of composition in order to focus more on the analysis of the painting technique. Always pursuing this goal, his still lifes also became less "fanciful," as they mainly represented the same subjects, primarily bottles, pitchers, vases, and bowls. So what made each work distinct from the others? The format, the point of view, and the light! In fact, Morandi focused on minimal variations in tone, although he preferred the use of shades of gray, ivory, and white, without forgetting to juxtapose saturated colors like orange, pink, and blue. What other constants can be added to his work? The painter used to paint with his typical gummed brushstrokes, aiming to create soft visions with "fluctuating" boundaries. This characteristic is due to the fact that bright light lightens the shadows, which, along with the light sources, are rendered using two-dimensional color fields that effectively tend to dematerialize the objects!

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli