With the arrival of the Salon du dessin 2025, which will bring together collectors, experts, and enthusiasts from around the world at the Palais Brongniart in Paris, this is the perfect moment to celebrate the fundamental role of drawing in the history of art.

From the most delicate studies to the boldest expressions, drawing has always been at the heart of artistic creation, offering a privileged glimpse into the minds of the greatest masters. In honor of this prestigious event, we present 10 essential drawings, timeless works that narrate the evolution of technique, vision, and creativity.

Andrea Mantegna, Man lying on a stone slab , 1470-80. Pen and ink drawing. British Museum Trustee.

Andrea Mantegna, Man lying on a stone slab , 1470-80. Pen and ink drawing. British Museum Trustee.

Andrea Mantegna – Man lying on a stone slab (1470-80)

The work Man lying on a stone slab, created between 1470 and 1480 using pen and ink, embodies Andrea Mantegna’s extraordinary ability to combine anatomical precision, expressive drama, and unprecedented illusionistic perspective. The depicted man, with his semi-reclined body and an expression of pain and abandonment, exudes a sculptural tension that makes him appear alive and tangible, almost three-dimensional in its realism. The artwork is now housed at the British Museum.

This drawing is in direct dialogue with Mantegna’s celebrated Dead Christ, preserved in the Pinacoteca di Brera. Both works share the same perspective research and the desire to experiment with anatomical foreshortening, a defining element of Mantegna’s art. The drawing does not precede the Dead Christ, but is contemporary to it, demonstrating how the artist was engaged in a deep exploration of the three-dimensional representation of the human figure. The body’s position, the extreme foreshortening, and the expressive intensity suggest a strong connection between the two works, united by the same plastic tension and fascination with spatial illusionism.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, 1490. Pen and ink drawing on paper. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, 1490. Pen and ink drawing on paper. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice.

Leonardo da Vinci – Vitruvian Man (1490)

Drawn by Leonardo da Vinci around 1490, Vitruvian Man is one of the most iconic images in the history of art. The work depicts a man inscribed within a circle and a square, demonstrating the ideal proportions of the human body according to the theories of the Roman architect Vitruvius.

The circle, symbolizing the cosmos and divine perfection, and the square, representing the earthly dimension, intersect within the human figure, which becomes the link between microcosm and macrocosm. This concept, derived from Platonic and Neoplatonic philosophy, reflects the Renaissance ideal of man as the measure of all things.

Leonardo’s style is distinguished by its extraordinary anatomical precision, the result of meticulous studies of the human body. Unlike previous Vitruvian representations, his drawing is based on direct observation, rather than simply replicating the classical text.

Leonardo da Vinci, Self-Portrait, 1517-18. Red chalk drawing on paper. Biblioteca Reale, Turin.

Leonardo da Vinci, Self-Portrait, 1517-18. Red chalk drawing on paper. Biblioteca Reale, Turin.

Leonardo da Vinci – Self-Portrait (1517-18)

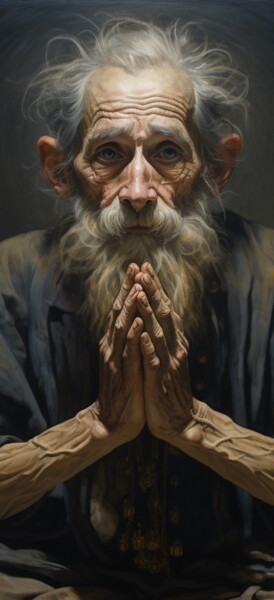

Leonardo da Vinci’s Self-Portrait, created around 1517, has defined the collective imagination of the Renaissance genius. This red chalk drawing on paper, characterized by a confident and fluid stroke, masterfully combines technical precision and deep psychological introspection. The subject, an elderly man with a timeworn face, gazes at the viewer with a penetrating and expressive look.

The subtle chiaroscuro, achieved through Leonardo’s masterful control of red chalk, gives the portrait a strong sense of volume and three-dimensionality, lending it an almost sculptural quality. His essential yet profound stroke, enriched with delicate shading, emphasizes the softness of the facial features and enhances the sense of depth.

Though originally conceived as an independent drawing, Leonardo’s Self-Portrait has greatly influenced the world of engraving, being reproduced and widely disseminated through prints since the 19th century. One of the earliest reproductions was made in 1810, when Giuseppe Bossi created an engraving of the portrait for his treatise Il Cenacolo di Leonardo da Vinci, further cementing its fame. The work resurfaced in 1839, when it became part of the House of Savoy collection, before being permanently housed in the Biblioteca Reale of Turin.

Although it is universally recognized as Leonardo’s authentic likeness, some scholars have questioned this identification over time, proposing that the subject might be Ser Piero da Vinci (his father), his uncle Francesco, or even a philosopher from antiquity. However, a comparison with Leonardo’s well-known profile drawing in Windsor, attributed to his pupil Francesco Melzi, has strengthened the idea that this is indeed a portrait of the Master in the final years of his life. This interpretation aligns with a 1517 description by Luigi d’Aragona’s secretary, who portrayed Leonardo as a man over seventy years old.

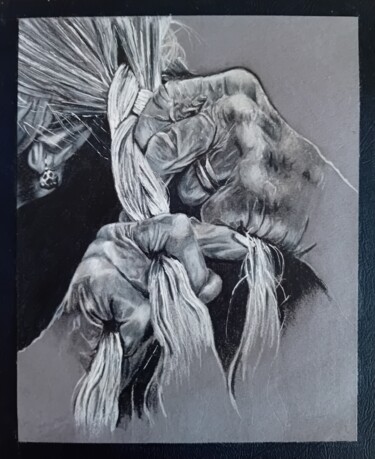

Albrecht Dürer, Praying Hands, c. 1508. Drawing. Albertina, Vienna.

Albrecht Dürer, Praying Hands, c. 1508. Drawing. Albertina, Vienna.

Albrecht Dürer – Praying Hands (c. 1508)

Albrecht Dürer’s drawing is a work that transcends time, recognized across the Western world as a universal symbol of faith and devotion. Created using pen and ink on blue-tinted paper, this masterpiece depicts two male hands joined in prayer, with slender fingers and wrists partially covered by rolled-up sleeves.

Dürer’s extraordinary attention to detail, from the refined chiaroscuro to the three-dimensional rendering, showcases his remarkable graphic skill, capable of imbuing even a simple anatomical study with deep expressiveness.

Traditionally, the drawing has been considered a preparatory study for the hands of an apostle meant to appear in the central panel of the Heller Altarpiece, commissioned for the Dominican church in Frankfurt and tragically destroyed in a fire in 1729. However, recent research suggests that the drawing was not merely a preliminary study, but rather a highly refined and virtuosic reworking of the hands painted in the altarpiece—an image that Dürer may have brought back to Germany after his renowned journey to Italy.

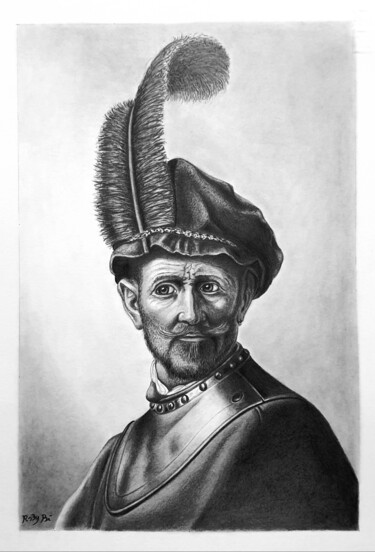

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Crucifixion for Vittoria Colonna, 1545. Charcoal on paper. British Museum, London.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Crucifixion for Vittoria Colonna, 1545. Charcoal on paper. British Museum, London.

Michelangelo Buonarroti – Crucifixion for Vittoria Colonna (1545)

Created around 1545, Crucifixion for Vittoria Colonna is a charcoal drawing on paper attributed to Michelangelo Buonarroti, now housed at the British Museum in London. This work is one of the most intimate examples of his graphic production, deeply connected to his friendship with Vittoria Colonna, a noblewoman and poet closely associated with Reformation circles.

Unlike traditional Crucifixion representations, Michelangelo’s Christ does not appear static on the cross, but rather seems to levitate, rising in a rotational movement. His body, modeled with extraordinary anatomical plasticity, twists in a way that conveys both pain and spiritual ascension, as if already projected toward resurrection. On either side, two mourning angels, rendered with essential lines, participate in the scene with intense emotional charge.

The dynamic interpretation of Christ’s body may reflect the influences of Catholic Reformation thought, which emphasized his death as the sole path to individual salvation, underscoring sacrifice as the ultimate act of redemption.

Raphael Sanzio, Study of the Heads and Hands of Two Apostles, 1519-20. Drawing. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Raphael Sanzio, Study of the Heads and Hands of Two Apostles, 1519-20. Drawing. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Raphael Sanzio – Study of the Heads and Hands of Two Apostles (1519-20)

This preparatory study for The Transfiguration, the grand altarpiece painted between 1518 and 1520, now housed in the Vatican Pinacoteca, is an extraordinary work that offers insight into the creative process of one of the greatest masters in art history.

The drawing presents two contrasting figures: a young man with an idealized face and an elderly man with a flowing beard, both immersed in intense emotional participation in the scene of the Healing of the Possessed Boy, depicted in the lower section of the painting. Raphael’s skill lies in his ability to characterize faces with extreme sensitivity, making the pathos of the scene almost tangible.

The black chalk stroke, handled with an exceptional tonal range, allows for a delicate modulation of light and shadow, foreshadowing the pictorial chiaroscuro of the final painting. This study is not merely an anatomical exercise, but a profound investigation into human nature and its conflicting emotions.

The sheet also reveals traces of pouncing, a technique used to transfer the outlines of the heads and hands from a larger full-scale preparatory cartoon. This demonstrates how the artist progressively refined the composition, focusing on the most expressive details to achieve perfection in pictorial execution.

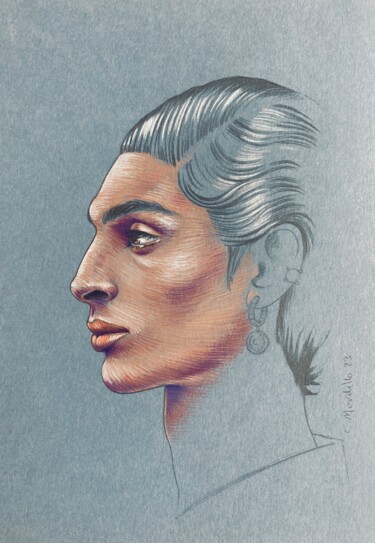

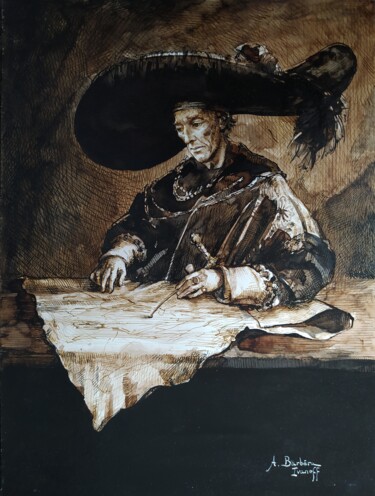

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1637. Red chalk. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1637. Red chalk. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

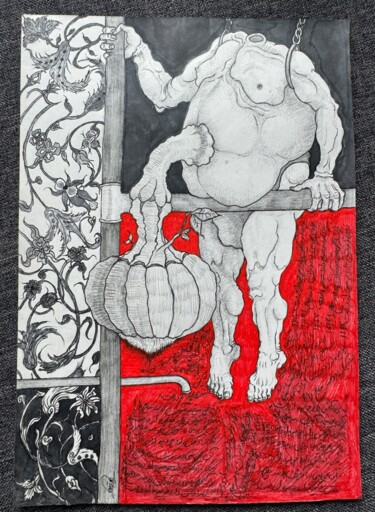

Rembrandt van Rijn – Self-Portrait (c. 1637)

Among Rembrandt’s vast collection of self-portraits, which includes over 40 paintings, 31 etchings, and several drawings, the red chalk portrait created around 1637, now housed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, stands out for its immediacy and expressive vitality.

In this work, Rembrandt portrays himself wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a richly pleated garment, yet the true focal point of the composition is his face, rendered with soft, fluid, and almost sketch-like lines, giving the figure a spontaneous and contemplative air. His direct and slightly ironic gaze, combined with a rapid and vibrant stroke, reveals not only his technical mastery but also his desire to continually explore his own image in new ways.

This drawing is part of Rembrandt’s lifelong self-examination, which runs throughout his career: from his early self-portraits, where he appears as an ambitious, emerging artist, to the powerful and melancholic portraits of old age, marked by deep shadows and introspection.

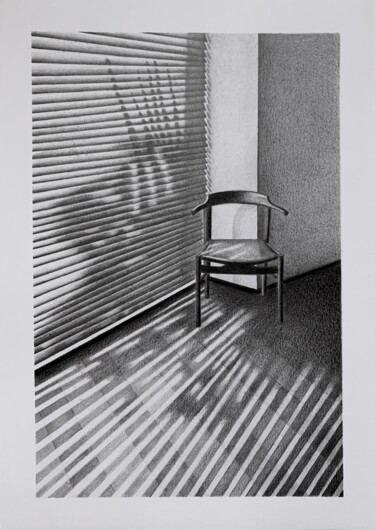

Edgar Degas, Danseuse Debout, c. 1877. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires.

Edgar Degas, Danseuse Debout, c. 1877. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires.

Edgar Degas – Danseuse Debout (c. 1877)

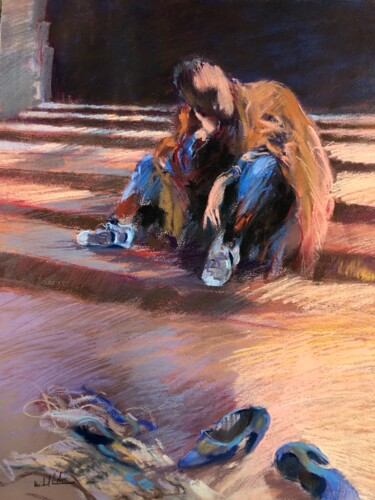

Among the artists who have captured the world of dance with extraordinary sensitivity, Edgar Degas holds a place of honor. His work Danseuse Debout (c. 1877), created in pastel on paper, is a perfect example of his ability to portray the movement, grace, and effort of the Paris Opéra ballerinas.

The drawing depicts a young dancer in a moment of preparation: her torso slightly inclined, one arm extended, and a leg raised, suggesting either a warm-up exercise or a moment of balance. Degas does not seek the perfect theatrical pose but rather the fleeting moment, the spontaneity of movement. The ballerina appears completely absorbed in her own world, without self-consciousness or performance, as if unaware of the artist’s gaze.

The choice of pastels, with their soft strokes and delicate color nuances, allows Degas to emphasize the luminosity of the tutu, the silk sheen of the tights, and the ballet slippers. His quick and vibrant lines seem to sculpt the figure with energy, while the undefined background draws attention to the dancer’s action, highlighting her movement and presence.

Vincent van Gogh, Sorrow, 1882. Drawing, The New Art Gallery Walsall, England.

Vincent van Gogh, Sorrow, 1882. Drawing, The New Art Gallery Walsall, England.

Vincent van Gogh – Sorrow (1882)

Created in 1882, Sorrow is one of Vincent van Gogh’s earliest graphic masterpieces, an intense and dramatic work that reveals the artist’s deep sense of empathy for the marginalized. This pencil and ink drawing depicts Clasina Maria Hoornik, known as Sien, a pregnant, abandoned woman, whose body bears the marks of a harsh life.

The female figure appears seated, her torso leaning forward, arms crossed over her legs, in a posture that expresses exhaustion, despair, and resignation. Her body is nude, yet devoid of idealization—it is a raw and realistic portrayal of human suffering.

The work is accompanied by the inscription:

“Comment se fait-il qu'il y ait sur la terre une femme seule, délaissée?” (How can there be on earth a woman alone, abandoned?), a quote from the historian Jules Michelet. This phrase provides a key interpretative element, revealing that the drawing is not just a portrait, but also a social denunciation of the plight of marginalized women in the 19th century.

Sien Hoornik was not just a model for Van Gogh but a woman with whom he shared a part of his life. He met her on the streets of The Hague in January 1882—she was pregnant, destitute, and forced into prostitution to survive. Van Gogh took her in and supported her for about a year, forming a bond that, for him, represented an act of charity and solidarity.

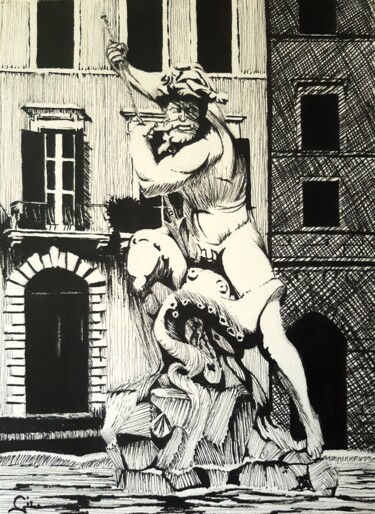

Pablo Picasso, Faun Revealing a Sleeping Woman (Jupiter and Antiope, after Rembrandt), 1936. Tate, London.

Pablo Picasso – Faun Revealing a Sleeping Woman (Jupiter and Antiope, after Rembrandt) (1936)

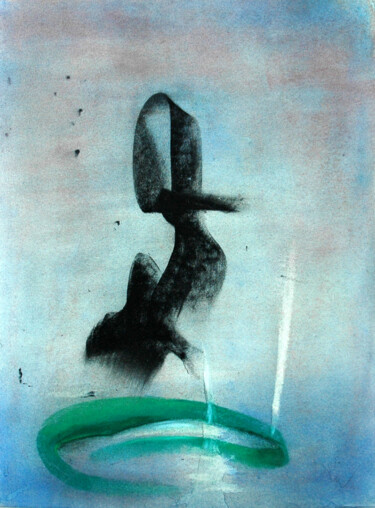

The work is inspired by an episode from classical mythology, previously depicted by Rembrandt in 1659: the story of Jupiter and Antiope, in which the god, disguised as a satyr, stealthily approaches the sleeping princess. However, Picasso’s reinterpretation goes far beyond the historical reference, transforming the theme into an image of strong erotic tension and narrative ambiguity.

The faun, a mythological figure associated with primal instincts and sexuality, leans over a sleeping woman, lifting the veil that covers her. The soft and opulent female body contrasts with the more aggressive and animalistic physique of the male creature, emphasizing the duality between passivity and dominance, dream and reality.

Picasso employs a combination of etching and drypoint, printmaking techniques that allow him to achieve a richness of lines and textures comparable to those of drawing. His fluid, swift lines appear almost sketched, while the intense shadows and scratched surfaces create a dramatic contrast, heightening the scene’s tension.

The similarity between this etching and Picasso’s graphic style is striking: the restless, fragmented stroke recalls his pencil and charcoal studies, while the chiaroscuro effects enhance the volume and three-dimensionality of the figures, as if they were first sculpted on paper before being etched onto the plate.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli