Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, 1511. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, 1511. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Michelangelo: The Perfection of the Human Body

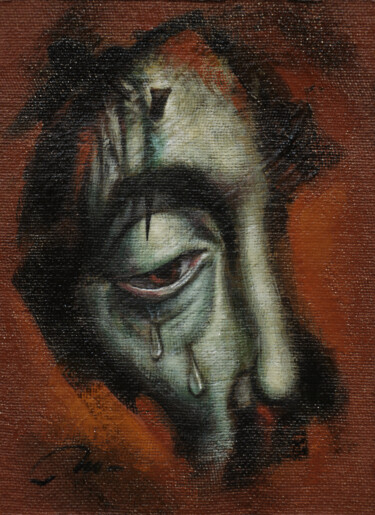

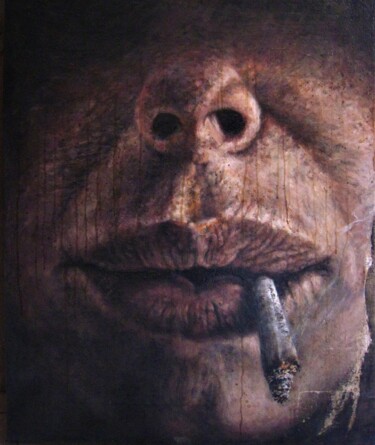

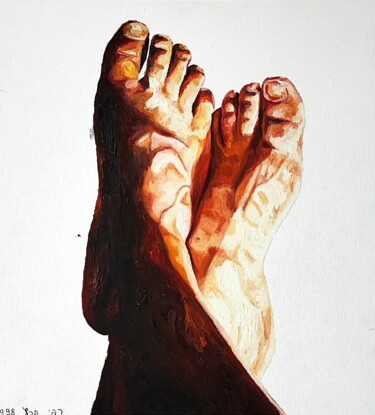

Looking at Michelangelo’s works, whether sculpted in marble or painted on ceilings and walls, what immediately strikes the viewer is the extraordinary depiction of the human body: taut muscles, natural poses, veins, tendons, and joints that seem to pulse beneath the marble skin. Michelangelo did not merely sculpt figures; he infused them with an almost supernatural vitality. His approach to anatomy was not based on intuition but was the result of meticulous, almost scientific study of the human body’s physical structure.

Like many great Renaissance masters, Michelangelo adhered to a key principle of classical art: the imitation of nature. However, in his case, it was an extreme, almost obsessive imitation, pushed to the utmost precision. To gain such knowledge of the human body, Michelangelo was not satisfied with external observation; he wanted to understand the internal mechanisms that animate every motion. That is why, from a young age, he practiced dissections of cadavers—despite their prohibition—to deeply study muscles, bones, nerves, and blood vessels.

This practice, carried out for years, even into his old age, allowed him to achieve a level of anatomical realism never seen before. Every figure he sculpted thus became not only an expression of an ideal of beauty but also of biological truth. It wasn’t simply about depicting strong or beautiful bodies; Michelangelo aimed to represent the very essence of the human body, in its physical complexity and spiritual power.

His style is distinguished by expressive intensity, where every muscle seems to vibrate with energy and internal tension. His figures are often caught in dynamic poses, in unstable balance that captures the moment before or after an action. This sense of movement and internal tension is one of the most recognizable hallmarks of his visual language: the human body is never static, but alive, dramatic, and charged with emotion.

Michelangelo did not seek the Platonic ideal of the perfect body but a powerful, carnal beauty, sometimes even exaggerated, capable of evoking strong emotions. His human figures are never merely physical; they are vessels of moral, spiritual, and heroic strength. The body thus becomes a language, through which to tell stories, tensions, and internal dramas.

Ultimately, Michelangelo elevated the study of anatomy from a mere technical tool to the expressive foundation of his art. In an era when the human being returned to the center of philosophical and artistic thought, Michelangelo made the body the absolute medium to express both the greatness and the fragility of man. Under his hands, marble was no longer just stone; it became flesh, energy, life.

From Renaissance Anatomy to Contemporary Sensibility: The Human Body as a Legacy of Italian Genius Michelangelo’s art laid the groundwork for a figurative tradition that has continued to influence generations of artists, in Italy and around the world. His depiction of the human body, so powerful, carnal, yet simultaneously spiritual and dramatic, has become a paradigm of beauty and expression for the entire Western visual culture. But what happens today when contemporary Italian artists confront the same subject? What does the human body look like today in Italian painting and sculpture?

The answer to this visual legacy lies precisely in the stylistic comparison that follows, between the unmatched genius of Michelangelo and some contemporary Italian painters featured on Artmajeur.

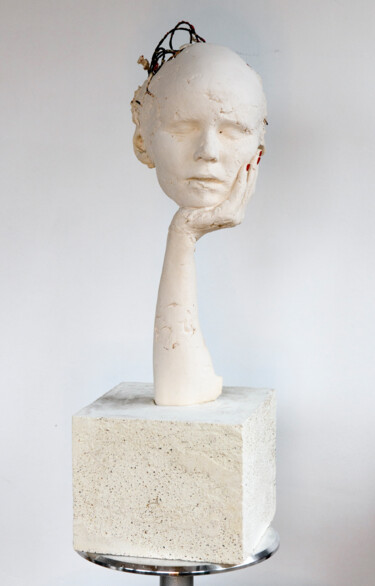

Morning - 2 (2024) Painting by Andrea Vandoni

Morning - 2 (2024) Painting by Andrea Vandoni

Andrea Vandoni, though working in a profoundly different artistic context, inherits from the Italian tradition a great attention to form and anatomy, but reinterprets it with a more intimate and narrative approach.

In the painting Morning - 2 (2024), the female body is treated with a delicate and sensitive realism, far from the monumentality of Michelangelo's work. The nude is no longer an absolute symbol of strength or divinity, but a living, intimate body, immersed in an everyday context. The woman depicted does not have the statuesque perfection of Renaissance figures, but a real, human beauty, characterized by soft chiaroscuro and a color palette that emphasizes natural light.

Unlike Michelangelo, who emphasized muscular tension and the heroism of the body, Vandoni prefers a serene, contemplative figure, almost suspended in a moment of transition. The pose is not tense but relaxed, and the gesture of opening the robe suggests an atmosphere of introspection and vulnerability.

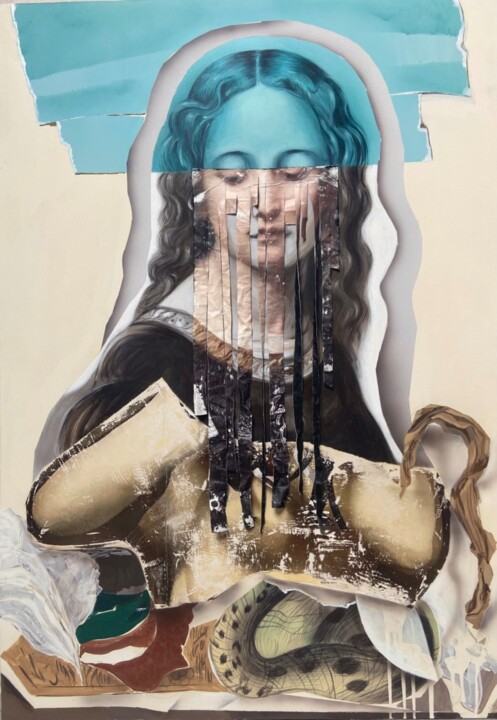

Andromeda (2022) Painting by Cavallaro & Martegani

Andromeda (2022) Painting by Cavallaro & Martegani

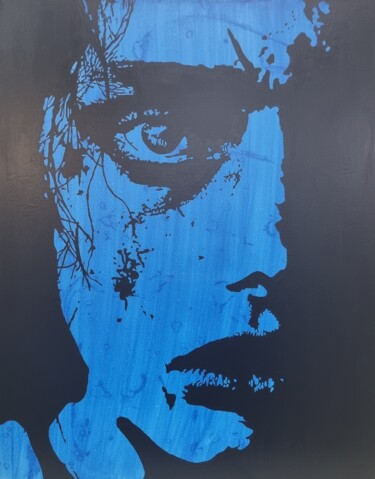

Centuries later, Andromeda by Cavallaro & Martegani confronts history painting in a completely new way: no longer through the celebration of the ideal form, but through the fragmentation and layering of the visual narrative. The artistic duo does not represent the body in its fullness, but deconstructs it, hides it, and breaks it down, suggesting that the history of art itself is a mosaic of perceptions, overlapping memories, and partial recollections.

If Michelangelo exalted the power of the flesh, Cavallaro & Martegani play with the ambiguity between presence and absence. Their painterly collage creates a visual effect where the body is almost an echo of the past, decomposed and recomposed through time. The use of tears, overlays, and different textures alludes to a discourse on time and memory, concepts that, albeit in completely different ways, were already present in Michelangelo, who sought in human anatomy a form of eternity.

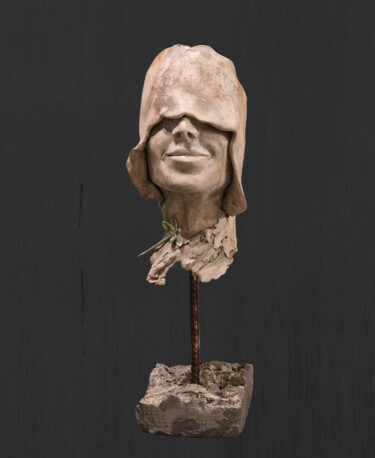

The sleeping muse (2024) Painting by Ivan Pili

The sleeping muse (2024) Painting by Ivan Pili

Ivan Pili's approach in "The Sleeping Muse" seems to embrace this classical legacy but reinterprets it with a modern pictorial language and a hyperrealist aesthetic. The female figure, with her perfectly outlined profile and soft chiaroscuro, evokes Greek deities and Renaissance muses, yet without the epic tension of Michelangelo. Here, the body is not exalted in movement and muscular strength, but in its delicacy and suspended sensuality.

The work recalls classicism not only in the representation of ideal beauty but also in the construction of the image. The woman appears immersed in a dreamlike timelessness, where the contrast between the bright softness of the skin and the black background echoes the dramatic lighting of Caravaggio. The large, precious bracelet on the wrist suggests a connection to the divine and aristocratic dimension, a detail that harks back to the classical iconographies of inspiring muses and goddesses of Greek mythology.

If Michelangelo conveyed the drama of humanity through the body, Pili tells of quiet and introspection, creating a figure that does not struggle with her condition, but gracefully surrenders to it. His hyperrealism is not cold and mechanical but is imbued with a sensitivity that transforms the woman into an almost metaphysical presence.

Figure 3 (2024) Painting by Will Paucar

Figure 3 (2024) Painting by Will Paucar

In Figure 3, Will Paucar presents a completely opposite vision. The body is emptied of identity, the face no longer exists, leaving only a shadow, an absence. The individual loses their recognizability and becomes something more universal, no longer a portrait but an abstract representation of the human condition.

The vibrant, contrasting pink background amplifies the sense of suspension: the absence of the face suggests a reflection on the soul, on erased identity, on the loss of self in the contemporary world. Paucar's approach is minimalist and conceptual, but at the same time powerful in its simplicity. While Michelangelo believed that the soul was revealed through the body, Paucar seems to suggest the opposite: when identity disappears, only the essence remains.

l'accettazione dell'incanto (2025) Painting byLaura Muolo

l'accettazione dell'incanto (2025) Painting byLaura Muolo

In "L'accettazione dell'incanto," Laura Muolo completely overturns the Michelangelesque perspective: existential dualism is no longer an "epic battle," but a colorful, sweet, and irresistible illusion that cannot be stopped but only accepted.

The young protagonist of the painting is surrounded by red and white lollipops, symbols of life's ephemeral sweetness. But these same candies drip, as if made of a substance that dissolves over time. As in the poem accompanying the work, the enchantment is temporary, impossible to hold onto, but no less captivating for that.

Bees and butterflies fluttering in the painting suggest a balance between wisdom and lightness, between instinct and consciousness. The girl does not seem to resist the temptation, nor does she completely give in to it: her gaze is enigmatic, as if she is aware of the illusion, yet simultaneously drawn to its beauty.

The use of color is fundamental in Muolo's narrative: the blue background, with its rounding shadows, creates a dreamy atmosphere, while the bright red of the drips and nails emphasizes the sensual and symbolic allure of temptation.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli