Rosalba Carriera, Aria, 1741-43. Galleria Corsini, Roma.

The Allegory of the Four Elements by Rosalba Carriera

In the vibrant heart of the 18th century, an era where grace and symbolism intertwine in art, Rosalba Carriera emerges as one of the most celebrated and sought-after painters in Europe. Born and raised in Venice, she captivates aristocratic courts and salons with her extraordinary mastery of pastels, a technique that, in her hands, acquires an almost ethereal softness and luminosity. With delicate yet precise strokes, Carriera manages to imbue the faces of her subjects with an expressive immediacy and psychological depth that were rare for the time.

Between 1741 and 1743, she created one of her most fascinating works for Giovan Francesco Stoppani, apostolic nuncio to the Senate of Venice: the allegorical series dedicated to the four elements. In a period when symbolic personifications—from continents to seasons—were a widely used artistic language, the Venetian painter brought to life an intense and refined depiction of Air, Water, Earth, and Fire, bestowing each figure with a distinctive character and a vibrant identity.

The four elements emerge prominently in the foreground, depicted with a portrait-like style that makes them appear almost alive, while their identifying iconographic attributes are elegantly placed at the edges of the composition. Air is draped in a deep blue cloak, with a piece of fabric subtly revealed, while a small bird tethered to a thread reinforces its connection to the invisible and the ephemeral. Water, contemplative and introspective, gazes at fish hanging from a fishing line, evoking the perpetual flow and mutability of this vital element. Earth appears solid and abundant, adorned with a garland of flowers in her hair and holding a cluster of grapes in her hands, symbolizing fertility and the cyclical nature of the seasons. Fire, finally, stands out for its vibrant energy: her flaming hair, the bright pink garment, and the small brazier she proudly holds in her hand evoke the transformative power of flames, a symbol of passion and destruction.

Now, it is time to delve deeper into how art has drawn further inspiration from nature, exploring the four elements—Earth, Air, Fire, and Water—which have been represented over the centuries with profound symbolic meanings and expressive modalities...

Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks, 1483-86. Oil on panel transferred to canvas. Louvre, Paris.

Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks, 1483-86. Oil on panel transferred to canvas. Louvre, Paris.

Other Examples from Art History

Earth: Stability, Nature, and Connection to the World

Earth has traditionally been associated with stability and connection to the physical world. In figurative art, it manifests through the depiction of landscapes, cultivated fields, towering mountains, or fertile valleys, symbolizing growth and continuity. It also evokes a sense of grounding and belonging, as well as the relationship between humans and their environment.

Many artists have explored this element, sometimes making it the symbolic focal point of their narratives. Leonardo da Vinci, in Virgin of the Rocks (1483), incorporates a rocky background to emphasize the relationship between nature and the sacredness of the scene. Before this master, Giotto had already experimented with integrating landscapes into his paintings to enhance the realism and depth of sacred scenes.

Turning to Jacob van Ruisdael (17th century), the Dutch painter’s landscapes often reflect the grandeur of nature and the relationship between humans and their surroundings. A significant example of this vision is Dune Landscape near Haarlem, an oil painting on canvas housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Finally, in contemporary times, artists such as Andy Goldsworthy are known for using the earth itself as material for their works, creating ephemeral installations that blend harmoniously with the natural landscape.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Air, 1566. Private Collection.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Air, 1566. Private Collection.

Air: Movement, Light, and Spirituality

Air represents lightness, thought, and the spiritual dimension. Invisible yet perceptible through its effects, this element is expressed in art through the depiction of the sky, moving clouds, wind stirring trees and fabrics, or the sensation of suspension and dynamism in the figures portrayed.

Among the numerous examples found throughout art history, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, in his painting Air, depicted a head composed entirely of birds, creating an image that symbolizes the lightness and ethereal essence of this element. J. M. W. Turner, in works such as Caernarvon Castle (1799), explored air in its atmospheric dimension, making the sky and light the true protagonists of the scene, conveying a sense of vastness and movement. Finally, Jean Béraud, in A Windy Day on the Pont des Arts, masterfully captures the effect of the wind through the movement of the clothing and accessories of passersby, making tangible what is normally intangible and transforming air into a living presence within the composition.

William Turner, The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 1835. Oil on canvas. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

William Turner, The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 1835. Oil on canvas. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

Fire: Passion, Destruction, and Rebirth

Fire, with its dual nature of destruction and creation, embodies passion, transformation, and renewal. Its blazing flames, often painted with vivid and intense colors, symbolize vital energy but also chaos and destruction. In art, this element can be interpreted as an emotional explosion, as seen in apocalyptic scenes and Romantic paintings of storms and fires, or as a purifying energy that marks a new beginning. Fire also represents inner strength, willpower, and struggle, expressed through dynamic and luminous forms.

Throughout art history, fire has been used to symbolize destruction and rebirth, as well as passion and fervor. William Turner, in The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons (1835), captures the devastating force of fire through vibrant brushstrokes, transforming the element into an expression of the sublime. Yves Klein, in contemporary art, uses fire as a creative medium, burning surfaces and canvases to generate works that speak of transformation and renewal. Similarly, Bill Viola, in his video installation Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) (2014), explores human resilience in the face of the elements, depicting human figures overwhelmed by natural forces.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Grenouillère, 1869. Oil on canvas. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Grenouillère, 1869. Oil on canvas. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

Water: Life, Emotion, and Depth

Water, finally, is synonymous with life, emotion, and transformation. Its fluidity makes it the symbol of constant change, reflection, and the unconscious. Art has often represented water in various forms: from turbulent seas expressing inner turmoil and deep passions, to rivers symbolizing the flow of time, to bodies of water that evoke mystery and introspection.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, in La Grenouillère (1869), represents water with light, vibrant brushstrokes, successfully conveying both its movement and the luminous reflections on its surface. Another significant example is The Baptism of Christ by Piero della Francesca, a 15th-century painting depicting Jesus being baptized by John the Baptist in the River Jordan. In this context, water plays a central role, symbolizing purification and spiritual rebirth. Lastly, The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai, a famous 19th-century Japanese woodblock print, is known for depicting a gigantic wave threatening boats, expressing the full power and dynamism of water.

Calligraphing en l' air #6 (2016) Photography by Cody Choi.

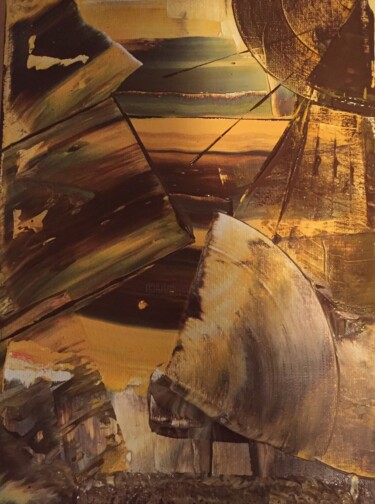

Fire Painting by Laura Casini.

Fire Painting by Laura Casini.

Four Contemporary Examples from ArtMajeur by YourArt

Air & Fire

The combination of air and fire in art is particularly evocative, as these two elements not only interact in nature but also enhance each other. Air fuels fire, making it flare up and spread, while fire transforms air, making it dense and full of energy. This dynamic relationship is reflected in the two contemporary artworks discussed here: Calligraphing en l'air #6 by Cody Choi and Fire by Laura Casini. Both explore movement, transformation, and expressive intensity, but they do so through two different artistic languages: photography and material painting.

Cody Choi's photographic work captures a moment of pure suspension, where the dancer’s body defies gravity and seems to dissolve into space. The concept of "writing in the air" becomes a metaphor for the dance itself, an ephemeral art that leaves invisible traces, yet full of meaning. Furthermore, the white background enhances the sense of lightness and weightlessness, while the contrast with the dancer’s dark figure—her hair tousled by the movement and the floating fabric—evokes wind and freedom. Air is thus not only the medium in which the body floats, but also a visible force through the movements of the fabric and hair, almost as if it were an active subject itself.

From the evanescence of air, we move to the burning presence of fire in Laura Casini’s painting. Here, energy manifests in a primordial form, through dense, rough, and glowing material. Red, orange, and yellow blend together on a vibrant surface, where the paint seems almost alive, bubbling and transforming before the viewer's eyes. The use of texture, with thick and irregular layers of color, recalls magma, live fire, combustion. The work is not just to be looked at but almost to be touched: the three-dimensionality of the color and the changing light effects on the surface create a sensory experience that goes beyond the visual.

The pairing of these two works is not accidental. Both speak of energy, but in opposing and complementary ways. The air in Cody Choi’s photograph is subtle, intangible, elusive; it is the breath of dance, the wind that lifts the body, the emptiness that allows flight. Fire in Laura Casini’s painting, on the other hand, is dense, burning, tangible; it is a force that burns, transforms, and leaves indelible traces.

Eau et fusain 7 (2023) Painting by Ln Le Cheviller

Eau et fusain 7 (2023) Painting by Ln Le Cheviller

Nous retournerons à la terre (2025) Painting by Emily Starck

Nous retournerons à la terre (2025) Painting by Emily Starck

Water & Earth

The combination of water and earth in art is not just a reference to nature, but also an exploration of their primordial relationship. Water shapes the earth, carves it, transforms it, making it fertile or eroding it, while the earth receives the water, holds its energy, and guides its flow. This ongoing interaction between stability and fluidity, between matter and movement, is expressed in two contemporary works that capture the visual and conceptual essence of these elements: Eau et fusain 7 by Ln Le Cheviller and Nous retournerons à la terre by Emily Starck.

Ln Le Cheviller’s work exists in an intermediate space between abstraction and landscape evocation, using water not only as a subject but also as a technique. Drips, gradients, and calligraphic traces seem to evoke the expansion of liquid surfaces, as if the painting itself were in motion. The diluted charcoal mixes with acrylic, creating an almost ethereal effect, a layering of transparencies that recalls the flow of water and its ability to shape space. Dominant tones of blue, black, and gray suggest depth and movement, with brushstrokes reminiscent of waves, currents, and whirlpools. Here, water is not represented traditionally but is suggested, leaving the viewer the task of perceiving its rhythm and fluidity.

While water represents movement and impermanence, earth symbolizes rooting, matter, and memory. Emily Starck’s evocatively titled Nous retournerons à la terre fits into the tradition of abstract expressionism, with a dense and material palette dominated by earthy tones like brown, yellow, and red. The artist addresses a universal, timeless theme: the bond between earth and death, the return to primordial matter, and the life cycle that renews itself through decomposition and rebirth. The gestural, layered brushstrokes lend the work a primordial, almost visceral force, as though the painting itself were a living organism that breathes and transforms. The surface of the canvas appears chaotic and vibrant, with marks that seem to emerge from the background like roots, sedimentations, or traces of an ancient history. Here, earth is not merely represented, but evoked in its deepest essence: an element that receives, preserves, and transforms.

Thus, these two works, despite belonging to different expressive registers, establish a powerful dialogue between the ephemeral and the enduring, between the flow of water and the solidity of earth.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli