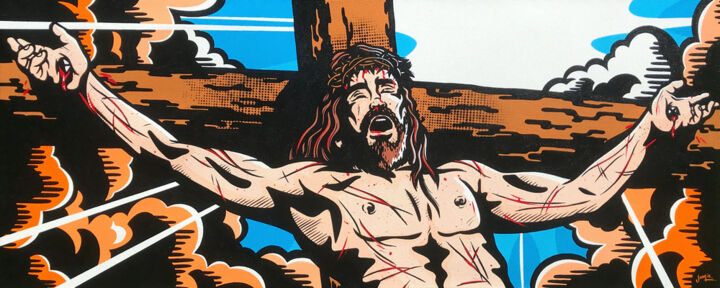

Jamie Lee, I love you this much, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 100 cm.

Jamie Lee, I love you this much, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 100 cm.

The story of the crucifixion of Christ: from the Gospel according to Mark to the works of art

The Gospel according to Mark, one of the four canonical gospels of the New Testament, describes to perfection the last moments of the life of the crucified Jesus:

When the sixth hour had come, it became dark over all the earth until the ninth hour. And at the ninth hour Jesus cried out in a loud voice: "Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachtàni?", which translated means: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?". And some of those present, hearing this, said, "See! Call Elijah." Then such a one went running and soaked a sponge with vinegar, and having placed it on a reed, gave him a drink, saying, "Let it be! Let's see if Elijah will come and lower it down." But Jesus, uttering a great voice, breathed his last. And the veil of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom. Now the centurion, who was present before him, seeing that he expired in this way, said, "Truly this man was the son of God" (Mark 15:33-39).

But how has this episode been narrated in the history of art?

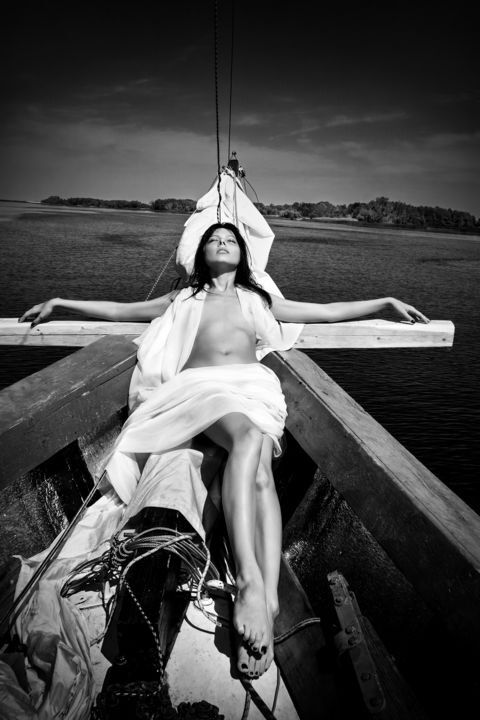

Vadim Fedotov, Soul of the ship, 2011. Photograph on paper, 95 x 65 cm.

Vadim Fedotov, Soul of the ship, 2011. Photograph on paper, 95 x 65 cm.

Jerome Excoffier, Crucifixion, 2020. Acrylic/oil on canvas, 122 x 100 cm.

Jerome Excoffier, Crucifixion, 2020. Acrylic/oil on canvas, 122 x 100 cm.

The crucifixion in the history of art

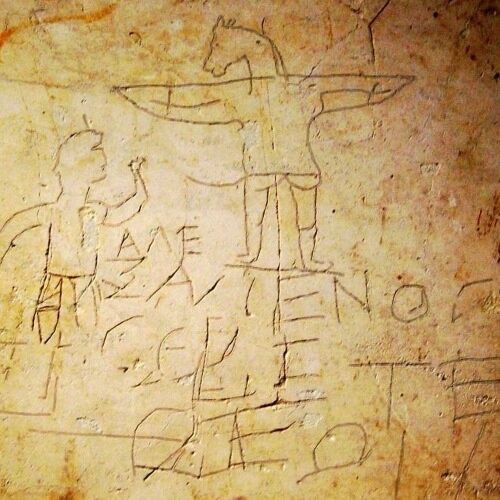

In the first centuries after the death of Jesus there is no art that has depicted his crucifixion. This silence seems to represent a serious anomaly, since the Roman world, in which Christianity spread, has always abounded in figurative representations having propaganda purposes. The reasons for this lack of images, however, were determined by the attitude of the early Church, which made clear reference to the prohibition of Jewish law: "You shall not make for yourself an idol or an image of what is up there in heaven or what is down here on earth, or what is in the waters beneath the earth. In fact, the first depiction of Christ on the cross, that is the Graffito of Alessameno (200 A.D.), comes from the world irrident towards the cult of Christianity, where such symbolism was mainly used to mock and shame. As for the first and "authorized" crucifixion of the art world, it dates back to 432 AD and was carved on a panel of the door of the Basilica of S. Sabina on the Aventine Hill in Rome, where Christ, with outstretched arms and open eyes, seems to have conquered death. Nevertheless, it was not until the Trullan Council II of 692 A.D. that the realistic representation of Christ in art became widespread, along with the importance of the Holy Cross and its veneration. From this moment on, however, were other questions that the Church posed, namely, how to portray Jesus crucified? Through a depiction of triumph or of despondency and mortification? Beginning in the sixth century, the second option was considered more appropriate in order to immortalize the one who, for the salvation of men, had taken on all the sins of the world. An example of what has been said is the Jesus, with his long face and large, hollow eyes, of the Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damian in Rome (6th century).

Graffito of Alessameno, 200 A.D. Rome: Palatine Antiquarium.

Graffito of Alessameno, 200 A.D. Rome: Palatine Antiquarium.

Panel of the Door of the Basilica of S. Sabina on the Aventine, 432 AD, Rome.

Panel of the Door of the Basilica of S. Sabina on the Aventine, 432 AD, Rome.

Subsequently, a further evolution of sacred art occurred in central Italy in the 12th century, where the first crosses painted directly on wood began to appear, to be hung on the triumphal arch of churches. In this context, the representation of the triumphal Christ was also affirmed for a brief period, but it was quickly replaced by the more traditional representation of the suffering Christ. This latter, with his head reclined on his shoulders, his eyes closed and his body bent in the spasm of pain, is perfectly exemplified by the iconic crucifix by Cimabue (1272-1280 circa), preserved in the basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. The dramatic exaltation of the dying Christ, however, finds its most famous manifestation in Giotto's crucifix (circa 1290-1295), on display in the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, the art of the painted wooden panel was replaced by that of the crucifix carved directly on wood, as evidenced by the wooden crucifix made by Brunelleschi, which, dated 1420, is preserved in the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

Cimabue, Crucifix of Santa Croce, 1272-1280 circa. Florence: basilica of Santa Croce. @metiderraneoantico

Giotto, Crucifix of Santa Maria Novella, 1290-1295 circa. Florence: Church of Santa Maria Novella. @abrunetty

Later, the Council of Trent (1545-1563) brought about a strong increase in this artistic production, since it attributed to art an important didactic and educational role. Subsequently, that is, from the 17th century onwards, the representations of Christ on the cross have largely diversified among themselves, interpreting techniques, stylistic innovations and expressions of personal and territorial devotion. Examples of what has been said can be both the Christ of St. John of the Cross (1951) by Salvador Dali, and the Piss Christ (1987) by Andres Serrano. In the first case, the Catalan master has pursued the intent to give life to an unprecedented Christ that, more beautiful and joyful than that of his predecessors, makes explicit reference to the Spanish tradition of the seventeenth century, aimed at depicting Jesus on the cross not in pain, but in solitude, or immersed in darkness. In addition, another element that makes the painting unique is the innovative perspective, aimed at conveying the idea that Christ with outstretched arms is intent on embracing the whole world from his cross. Finally, as for the photograph Piss Christ by Andres Serrano, it captured a small plastic crucifix immersed in a glass tank containing urine. Such insulting treatment of the image of Jesus, is actually meant to allude to the feeling of shame and disgust, which one feels when observing any image of torture and death. Moreover, Serrano's provocative act is intended to demonstrate how the viewer, who has become too familiar with traditional representations, is able to feel outrage only through more extreme images.

Salvador Dali, Christ of St. John of the Cross, 1951. Oil on canvas, 205 × 116 cm. Glasgow: Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. @teodorougone

Andres Serrano, Piss Christ, 1987. @nationamuseumswe

Claude Duvauchelle, Christian Figuration-XI Version-2. Painting on canvas, 195 x 130 cm.

Claude Duvauchelle, Christian Figuration-XI Version-2. Painting on canvas, 195 x 130 cm.

The Crucifixion of Christ in the works of the artists of Artmajeur

The eternal topicality of the crucifixion of Christ within the art world is well exemplified by the work of the artists of Artmajeur, ready to provide us with a faithful snapshot of the most innovative, irreverent and fashionable techniques, styles and points of view of our contemporaneity. In particular, the works of Régis Gomez, Alessandro Flavio Bruno and Van Ko Tokusha represent up-to-date and original points of view that, even if sometimes blasphemous and irreverent, allow us to establish a strong link with the highest figurative tradition of the past.

Régis Gomez, Crucifixion, 2022. Sculpture made of wood / metal / stone / plaster / resin / sand, 26,5 x 18 x 18 cm / 1,00 kg.

Régis Gomez, Crucifixion, 2022. Sculpture made of wood / metal / stone / plaster / resin / sand, 26,5 x 18 x 18 cm / 1,00 kg.

Régis Gomez: Crucifixion

The sculpture of the Belgian artist, Régis Gomes, takes up the theme of the crucifixion of Christ, reinterpreting it within the modern context. In fact, if in the Roman world slaves, subversives and foreigners were crucified, in the same world, now, a can of Coca-cola is punished, a symbol of unacceptable consumerism and dangerous pollution. In addition, Crucifixion, which can also be a little blasphemous, reminds to another sculpture that has taken sides against the dynamics of the contemporary world, namely McJesus by Janei Leinon. In fact, this latter crucifixion depicts the McDonald's clown instead of Christ, with the intention of denouncing the unbridled consumerism fed by the most well-known multinational corporations.

Alessandro Flavio Bruno, Ecce chrome, 2021. Acrylic / plaster / enamel / tempera / aluminum / metals / plastic on wood, 70 x 43 cm.

Alessandro Flavio Bruno, Ecce chrome, 2021. Acrylic / plaster / enamel / tempera / aluminum / metals / plastic on wood, 70 x 43 cm.

Alessandro Flavio Bruno: Ecce chrome

Once again the crucifixion of Christ in art, to which the title of the artwork also alludes, is used as a means to denounce the evils of contemporary society. In fact, Ecce chrome, the first work of the Dead language series, represents a sort of crucifixion of color that, intended as pictorial art, is increasingly replaced by new technologies and installations. Therefore, the painting announces the death of painting, which, perhaps now exhausted in its capacity for innovation, deserves only the crucifixion.

Van Ko Tokusha, Crucifixion, 2021. Encaustic / pastel / wax / wood / wood engraving, 36.8 x 61.3 cm.

Van Ko Tokusha, Crucifixion, 2021. Encaustic / pastel / wax / wood / wood engraving, 36.8 x 61.3 cm.

Van Ko Tokusha: Crucifixion

The artwork of the Bulgarian artist, Van Ko Tokusha, represents a more "classical" vision of the crucifixion of Christ, of which, however, only one vivid detail is represented: the right hand of Jesus now pierced by a nail. In this "traditional" context, however, details of the contemporary world also stand out, such as the features of the nail and the architecture in the background. Finally, the subject of this painting represents a clear demonstration of the popularity of the crucifixion of Christ within Western culture, as it is now well recognizable and understandable even just through its most iconic details.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli