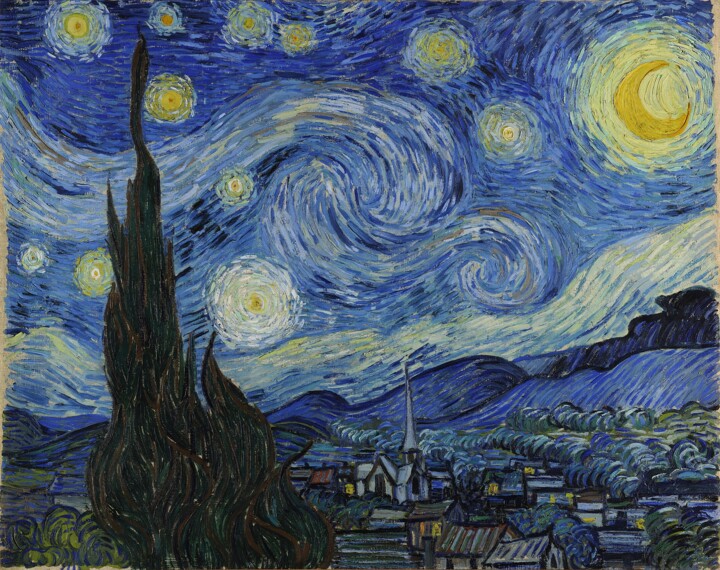

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1887. Oil on artist's board, mounted on cradled panel, 41 × 32.5 cm. Art Institute of Chicago.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1887. Oil on artist's board, mounted on cradled panel, 41 × 32.5 cm. Art Institute of Chicago.

Who was Vincent van Gogh?

Vincent Willem van Gogh, a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter, is recognized as one of the most significant and influential figures in Western art history. Despite facing struggles with depression and poverty, he created approximately 2,100 artworks over a span of ten years. His collection includes around 860 oil paintings, with the majority produced during the last two years of his life. Van Gogh's works encompassed landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, characterized by vibrant colors, bold brushwork, and expressive techniques that played a crucial role in shaping modern art.

Born into an affluent family, Van Gogh displayed artistic talent from an early age and possessed a serious and introspective demeanor. As a young man, he worked as an art dealer and frequently traveled, but his spirits plummeted after being transferred to London. Seeking solace, he turned to religion and worked as a Protestant missionary in predominantly Catholic southern Belgium. Following a period of solitude and declining health, he ventured into painting in 1881, returning to live with his parents. Financial support from his brother Theo sustained him, and they maintained a lengthy correspondence through letters. Van Gogh's early works primarily consisted of still lifes and depictions of laborers, lacking the vivid coloration that would later distinguish his art. In 1886, he relocated to Paris, where he encountered avant-garde artists such as Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, who were reacting against the Impressionist movement. As his style evolved, Van Gogh adopted a fresh approach to still lifes and local landscapes. His paintings grew progressively brighter, culminating in his fully realized style during his stay in Arles, in the South of France, in 1888. During this period, he expanded his subjects to include series of olive trees, wheat fields, and sunflowers.

Van Gogh battled psychotic episodes, delusions, and concerns about his mental stability. Neglecting his physical well-being, he suffered from poor eating habits and heavy drinking. His friendship with Gauguin disintegrated following a confrontation that led Van Gogh to sever a portion of his own left ear in a fit of rage. He spent time in psychiatric hospitals, including a period at Saint-Rémy. Eventually settling in the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, he received care from homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet. However, his depression persisted, and on July 29, 1890, Van Gogh allegedly shot himself in the chest with a revolver, succumbing to his injuries two days later.

During his lifetime, Van Gogh struggled to achieve commercial success, and he was regarded as both mentally unstable and a failure. It was only after his death that he gained recognition, with the public viewing him as a misunderstood genius. In the early 20th century, his artistic style influenced the Fauvists and German Expressionists. Over the years, he attained widespread critical acclaim and commercial success, embodying the romanticized archetype of the tormented artist. Today, Van Gogh's paintings are among the most expensive artworks ever sold, and his legacy is preserved in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which houses the largest collection of his paintings and drawings.

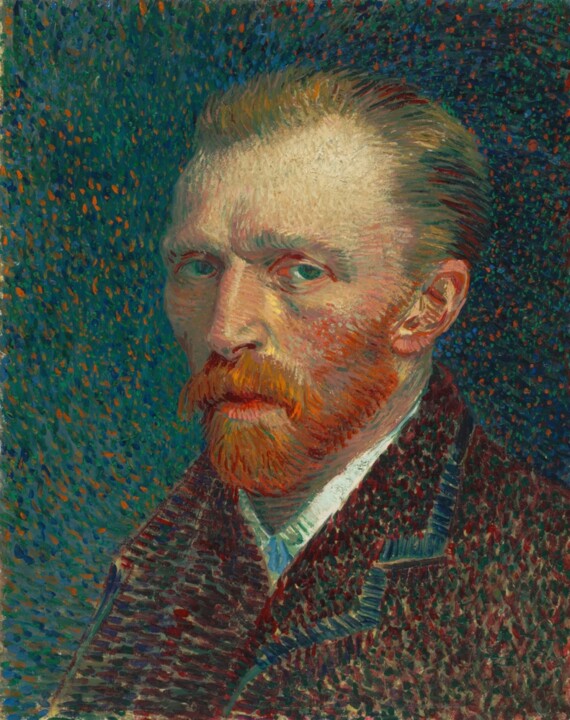

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889. oleograph on canvas, 73.7×92.1 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889. oleograph on canvas, 73.7×92.1 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Starry Night

The Starry Night is an oil painting on canvas created by Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter. Executed in June 1889, the artwork portrays the scene visible from Van Gogh's asylum room window in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, facing east, just before the break of dawn. In addition to the natural landscape, Van Gogh incorporated an imaginary village into the composition. Since 1941, The Starry Night has been a part of the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, having been acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. It is widely acclaimed as Van Gogh's greatest masterpiece and stands as one of the most easily recognizable paintings in the realm of Western art.

Description

In the nocturnal setting of a countryside, Vincent van Gogh depicts a captivating scene. The houses come to life with illuminated windows, while a crescent moon casts its gentle glow upon an otherworldly sky filled with mesmerizing swirls. Against a backdrop of a starry expanse, with the crescent moon positioned in the upper right and the radiant presence of Venus on the left, van Gogh masterfully captures the essence of a country landscape. At the center-bottom, a petite church stands with its tall bell tower, surrounded by humble rural dwellings. Interrupting the scenery on the left, a prominent, twisted cypress tree emerges, casting a dark and intriguing silhouette. Beyond the village, on the right, a dense forest looms, seeming to descend upon the town like a crashing tidal wave. Finally, on the distant horizon, colossal hills and mountains resemble immense waves hurtling towards the houses, evoking a sense of grandeur and dramatic tension.

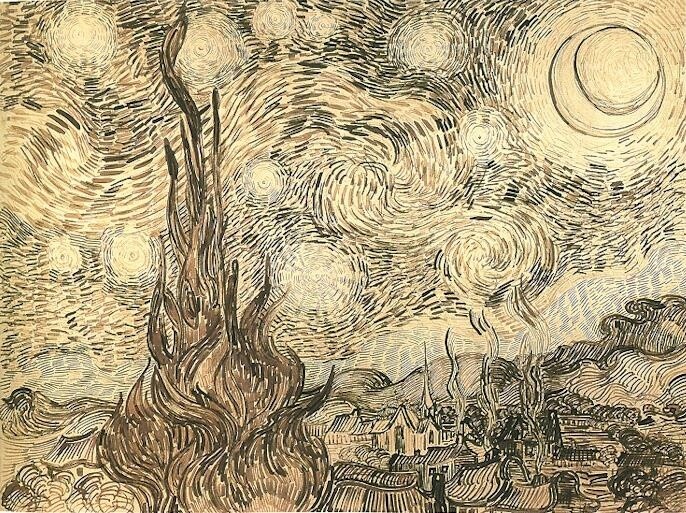

The drawing Cypresses in Starry Night, a reed pen copy executed by Van Gogh after the painting in 1889. Originally held at Kunsthalle Bremen, today part of the disputed Baldin Collection.

The drawing Cypresses in Starry Night, a reed pen copy executed by Van Gogh after the painting in 1889. Originally held at Kunsthalle Bremen, today part of the disputed Baldin Collection.

Interpretations

Despite Van Gogh's extensive correspondence, he provided very little information about The Starry Night. He briefly mentioned the painting in June when he reported painting a starry sky. Then, around September 20, 1889, he included it in a list of paintings he was sending to his brother Theo in Paris, referring to it as a "night study." In this list, he expressed mixed feelings about his works, stating that only a few were good in his opinion, and the rest did not resonate with him. The Starry Night fell into the latter category. When he decided to withhold three paintings from the batch he was sending to save on postage, The Starry Night was among the paintings he held back. In a letter to painter Émile Bernard in late November 1889, Van Gogh even described the painting as a "failure."

Van Gogh engaged in debates with artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard regarding the approach to painting. Gauguin advocated for what he called "abstractions," paintings conceived in the imagination, while Van Gogh preferred painting from nature. In the letter to Bernard, Van Gogh recounted his experiences when Gauguin lived with him in Arles, expressing that he was led astray into abstraction but ultimately found it delusional and unfulfilling. He referred specifically to the expressionistic swirls dominating the upper center of The Starry Night.

Theo mentioned these elements in a letter to Vincent on October 22, 1889, acknowledging the focus on style in Vincent's new paintings, such as the village in moonlight (The Starry Night) or the mountains. However, he felt that this search for style compromised the true sentiment of the artwork. Vincent responded in early November, expressing his inclination towards seeking style, particularly through more deliberate and masculine drawing. He acknowledged that this might make his work resemble Bernard or Gauguin but believed that over time, Theo would become accustomed to it. He emphasized the importance of expressing the entanglement of masses through a drawing style that incorporated long, sinuous lines, although he admitted that his previous studies did not achieve what they were intended to be.

However, despite occasional defense of Gauguin and Bernard's practices, Van Gogh consistently distanced himself from their approaches and continued to adhere to his preferred method of painting from nature. Similar to the impressionists he encountered in Paris, particularly Claude Monet, Van Gogh also embraced the concept of working in series. In Arles, he painted a series of sunflowers, and during his time in Saint-Rémy, he embarked on series featuring cypresses and wheat fields. The Starry Night belongs to the latter series, as well as a smaller series of nocturnes that he initiated in Arles. However, painting nocturnal scenes presented challenges due to the difficulties of capturing such scenes from nature, especially at night.

The first painting in the nocturne series was Café Terrace at Night, completed in early September 1888 in Arles, followed by Starry Night (Over the Rhône) later in the same month. Van Gogh's written statements about these paintings shed light on his intentions for creating night studies in general and The Starry Night in particular.

Shortly after arriving in Arles in February 1888, Van Gogh expressed his desire to paint a starry night with cypresses or a field of ripe wheat. He considered the starry sky as something he wished to capture, much like his intention to paint a green meadow adorned with dandelions during the daytime. He likened the stars to dots on a map and contemplated that just as one takes a train to travel on Earth, death becomes a means to reach a star.

Moon detail.

Moon detail.

Although Van Gogh was disillusioned with religion at that point in his life, he seemed to retain a belief in an afterlife. He expressed this conflicting sentiment in a letter to Theo after completing Starry Night Over the Rhône, admitting to a "tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion—so I go outside at night to paint the stars."

Van Gogh wrote about the concept of existing in another dimension after death and associated this dimension with the night sky. He expressed the idea that life would be simpler if there were another invisible hemisphere where one would land after death, which would explain the hardships of life. He found hope in the stars, recognizing that Earth itself is a planet and a celestial orb. However, he firmly stated that The Starry Night was not a return to romantic or religious ideals.

Art historian Meyer Schapiro emphasizes the expressionistic qualities of The Starry Night, describing it as a visionary painting inspired by a religious atmosphere. Schapiro suggests that the painting's hidden content alludes to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament, depicting an apocalyptic theme of a woman in the pain of childbirth, adorned with the sun, moon, and stars, while her newborn child is threatened by a dragon. Schapiro also interprets Landscape with Olive Trees, painted around the same time, as portraying an image of a mother and child in the clouds, often considered a pendant to The Starry Night.

Building on Schapiro's interpretation, art historian Sven Loevgren describes The Starry Night as a visionary painting conceived in a state of intense emotional turmoil. He acknowledges the hallucinatory nature and violently expressive form of the artwork, although he clarifies that it was not created during one of Van Gogh's incapacitating breakdowns. Loevgren compares Van Gogh's longing for the beyond, driven by his religious inclination, to the poetry of Walt Whitman. He considers The Starry Night to be an incredibly expressive picture that symbolizes the artist's complete absorption into the cosmos and evokes a profound sense of standing on the threshold of eternity. Loevgren commends Schapiro's interpretation of the painting as an apocalyptic vision and adds his own symbolist theory, referencing Joseph's dream in the Book of Genesis, where eleven stars held symbolic significance. Loevgren asserts that the visual elements in The Starry Night are depicted purely in symbolic terms and notes that the cypress tree is traditionally associated with death in Mediterranean countries.

Venus detail.

Venus detail.

Art historian Lauren Soth proposes a symbolist interpretation of The Starry Night, suggesting that the painting conceals a traditional religious subject and reflects Van Gogh's profound religious sentiments. Soth points to Van Gogh's admiration for Eugène Delacroix's paintings, particularly the use of Prussian blue and citron yellow to depict Christ, and theorizes that Van Gogh employed these colors to symbolize Christ in The Starry Night. Soth critiques Schapiro's and Loevgren's biblical interpretations, which rely on the crescent moon incorporating elements of the Sun, asserting that the moon is simply a crescent with symbolic meaning for Van Gogh, representing "consolation."

Taking into account these symbolist interpretations, art historian Albert Boime presents his analysis of The Starry Night. Boime confirms that the painting portrays not only the geographical elements of Van Gogh's view from his asylum window but also celestial features, identifying Venus and the constellation Aries. He suggests that Van Gogh initially intended to paint a gibbous moon but later reverted to a more traditional depiction of a crescent moon. Boime theorizes that the bright halo surrounding the crescent represents a remnant of the original gibbous version. He discusses Van Gogh's interest in the works of Victor Hugo and Jules Verne, speculating that they may have influenced Van Gogh's belief in an afterlife on stars or planets. Boime also delves into the significant advancements in astronomy during Van Gogh's lifetime.

Although Van Gogh never mentioned astronomer Camille Flammarion in his letters, Boime believes that Van Gogh must have been aware of Flammarion's popular illustrated publications, which included drawings of spiral nebulae (then referred to as galaxies) as seen and photographed through telescopes. Boime interprets the swirling figure in the central portion of the sky in The Starry Night as either a spiral galaxy or a comet, both of which had been depicted in popular media. He argues that the only non-realistic elements in the painting are the village and the sky's swirls, which symbolize Van Gogh's perception of the cosmos as a vibrant and dynamic entity.

Harvard astronomer Charles A. Whitney conducted his own astronomical analysis of The Starry Night concurrently with Albert Boime's research. Although Whitney does not share Boime's certainty about the depiction of the constellation Aries, he agrees that Venus would have been visible in Provence during the painting's execution. Like Boime, Whitney identifies a spiral galaxy in the sky, but he credits Anglo-Irish astronomer William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, for the original discovery, which was later reproduced by Flammarion. Whitney proposes that the swirls in the sky may represent the mistral, a strong wind that had a significant impact on Van Gogh during his time in Provence. Boime suggests that the lighter shades of blue near the horizon depict the first light of morning.

Vincent van Gogh, The Cafe Terrace On The Place du Forum, Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas, 81×65.5 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

Vincent van Gogh, The Cafe Terrace On The Place du Forum, Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas, 81×65.5 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

The village in The Starry Night has been interpreted in different ways, either as a recollection of Van Gogh's Dutch homeland or based on a sketch he made of the town of Saint-Rémy. Regardless, it is an imaginary element in the painting and not visible from the window of Van Gogh's asylum bedroom.

Cypress trees have historically been associated with death in European culture, although there is an ongoing debate about whether Van Gogh intended them to have symbolic meaning in The Starry Night. In a letter to Bernard in April 1888, Van Gogh referred to "funereal cypresses," although this could be akin to saying "stately oaks" or "weeping willows." Shortly after completing the painting, Van Gogh expressed his fascination with the cypresses, wanting to create artworks featuring them similar to his sunflower series. This suggests that he was more interested in their formal qualities rather than their symbolic connotations.

Schapiro characterizes the cypress in The Starry Night as a vague symbol of human striving, while Boime interprets it as a symbolic representation of Van Gogh's own pursuit of the Infinite through unconventional means. Jirat-Wasiutynski sees the cypresses as rustic and natural obelisks that bridge the gap between heaven and earth. Different commentators perceive different numbers of cypress trees in the painting.

Pickvance asserts that The Starry Night, with its combination of disparate motifs, is clearly marked as an abstraction. He argues that the cypresses, along with the village and the swirling sky, are products of Van Gogh's imagination, as they would not have been visible from his room facing east. However, Boime and Jirat-Wasiutyński maintain that the cypresses would have been visible in that direction. Naifeh and Smith, Van Gogh biographers, agree that Van Gogh compressed the view in certain paintings of the scene from his window, enhancing the brightness of the Morning Star.

Soth uses Van Gogh's statement about The Starry Night being an exaggeration in terms of arrangement to support his argument that the painting is a combination of different images. However, it is uncertain whether Van Gogh used "arrangement" as a synonym for "composition." Van Gogh's comment actually referred to three paintings, including The Starry Night, and he described the olive trees with white cloud and mountains, as well as the moonrise, as exaggerations in terms of arrangement. The first two paintings are widely accepted as realistic, non-composite representations of their subjects. The commonality among the three paintings lies in their exaggerated colors and brushwork, which Theo criticized for detracting from the genuine sentiment of The Starry Night.

During this period, Van Gogh used the term "arrangement" to describe color in a similar way to James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In a letter to Gauguin, he discussed the arrangement of colors in La Berceuse, praising the progression from reds to oranges, flesh tones, chromes, pinks, and olive and Veronese greens. He considered it his best impressionist arrangement of colors. In another letter to Bernard, he admired the beautiful and naively distinguished arrangement of colors in Gauguin's painting of Breton women walking in a meadow, contrasting it with something artificial and affected.

Naifeh and Smith discuss The Starry Night in relation to Van Gogh's mental illness, which they believe was temporal lobe epilepsy. They describe it as a mental epilepsy, causing a collapse of thought, perception, reason, and emotion within the brain. The symptoms resembled electrical impulses and resulted in bizarre and dramatic behavior. They suggest that Van Gogh's second breakdown in July 1889 was influenced by the seeds of instability present during the painting of The Starry Night. They argue that Van Gogh, in a heightened state of reality, surrendered to his imagination and created a night sky that was unprecedented in its depiction.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night over the Rhone, 1888. Oil on canvas, 72.5×92 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night over the Rhone, 1888. Oil on canvas, 72.5×92 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Historical context

Following the distressing event on December 23, 1888, when Vincent van Gogh mutilated his own left ear, he voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole lunatic asylum on May 8, 1889. Located in a converted monastery, the asylum mainly catered to affluent individuals and had plenty of vacant space when Van Gogh arrived. As a result, he was able to occupy not only a second-floor bedroom but also a ground-floor room that he transformed into a studio for his painting endeavors.

During his time at the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, which spanned approximately one year, Van Gogh's prodigious artistic output from his earlier period in Arles continued. This period yielded some of his most renowned works, such as the famous Irises painted in May 1889, now housed at the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the striking blue self-portrait created in September 1889, on display at the Musée d'Orsay. The Starry Night, an iconic piece, was completed in mid-June, around June 18th, as indicated in his letter to his brother Theo, where he mentioned his new study of a starry sky.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890. Oil on canvas, 50.5×103 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890. Oil on canvas, 50.5×103 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

History of the painting

Despite The Starry Night being painted during daylight hours in Vincent van Gogh's ground-floor studio, it would be incorrect to assume that it was solely based on his memory. The depicted view is identified as the scene visible from his bedroom window, facing east. Van Gogh explored various iterations of this view, including The Starry Night, in at least twenty-one different paintings. In a letter to his brother Theo around May 23, 1889, he described the sight he observed through the iron-barred window, stating, "I can see an enclosed square of wheat... above which, in the morning, I watch the sun rise in all its glory."

Van Gogh depicted the view at different times of the day and in diverse weather conditions, capturing scenes such as sunrise, moonrise, sunny days, overcast days, windy days, and even a rainy day. Although he was not allowed to paint in his bedroom, he made sketches using ink or charcoal on paper, using them as references for newer variations of the view. One consistent element across these paintings is the diagonal line from the right, representing the gentle rolling hills of the Alpilles mountains. In fifteen of the twenty-one versions, cypress trees can be seen beyond the enclosing wall of the wheat field. Van Gogh exaggerated their proportions in six of these paintings, most notably in Wheat Field with Cypresses and The Starry Night, bringing the trees closer to the forefront of the composition.

One of the initial paintings capturing the view was Mountainous Landscape Behind Saint-Rémy, which is currently held in Copenhagen. Vincent van Gogh created several sketches as preparatory work for this painting, including The Enclosed Wheatfield After a Storm, which serves as a typical example. It is uncertain whether the painting itself was done in Van Gogh's studio or outdoors. In a letter dated June 9, he mentioned that he had been working outside for a few days when describing this particular piece. Van Gogh also referred to another landscape he was working on in a letter to his sister Wil on June 16, 1889. This landscape is known as Green Wheat Field with Cypress, currently located in Prague, and it was the first painting he definitely painted en plein air at the asylum. Wheatfield, Saint-Rémy de Provence, now housed in New York, serves as a study for this work. Two days later, Vincent wrote to Theo, stating that he had painted "a starry sky."

Hills and sky detail.

Hills and sky detail.

Among the series of views from his bedroom window, The Starry Night is the only painting depicting a nocturnal scene. In early June, Van Gogh wrote to Theo, describing how he observed the countryside from his window long before sunrise, with only the morning star, which appeared noticeably prominent. Researchers have confirmed that Venus (sometimes referred to as the "morning star") was indeed visible at dawn in Provence during the spring of 1889, shining with exceptional brightness. Therefore, the brightest "star" depicted in the painting, just to the right of the cypress tree, is actually Venus.

The depiction of the moon in The Starry Night is stylized, as astronomical records indicate that it was actually in the waning gibbous phase when Van Gogh painted the picture. Even if the moon had been in its waning crescent phase at the time, Van Gogh's portrayal of the moon would not have been astronomically accurate. The one element in the painting that Van Gogh could not have observed from his cell is the village. It is based on a sketch (F1541v) he made from a hillside above the village of Saint-Rémy. Some experts, like Pickvance, believed that F1541v was done later, and the steeple depicted had more of a Dutch influence than a Provençal one, combining elements from various works Van Gogh created during his Nuenen period. This marked the beginning of his "reminiscences of the North," which he would continue to paint and draw early the following year. Hulsker suggested that a landscape on the reverse side (F1541r) also served as a study for the painting.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei