Historical Background

Shōgatsu (正月), the Japanese New Year, is an annual celebration in Japan that takes place according to the Gregorian calendar on January 1. This tradition was established in 1873, following the adoption of the Gregorian calendar five years after the Meiji Restoration. Before this shift, the Japanese New Year was celebrated based on the lunisolar calendar, specifically the Tenpō calendar, which was the last official lunisolar calendar used in Japan.

The transition from the lunisolar to the Gregorian calendar marked a significant change in how the New Year was observed. During the Meiji period, Japan embraced numerous Western customs and technologies, which included the synchronization of its calendar with the Western world. This change was part of a broader effort to modernize Japan and integrate it into the international community.

Shōgatsu is the most important holiday in Japan, a time when businesses close from January 1 to January 3, allowing families to gather and celebrate together. Traditionally, the New Year is viewed as a time for renewal, with all duties completed by the end of the previous year. This is reflected in customs such as bonenkai parties, which are held to forget the troubles of the old year, and extensive cleaning of homes to prepare for a fresh start.

On New Year’s Eve, families enjoy toshikoshi soba, buckwheat noodles symbolizing longevity, and many watch the popular music show "Kohaku Uta Gassen." New Year's Day, known as Ganjitsu (元日), is considered very auspicious. It begins with hatsu-hinode, viewing the first sunrise of the year, which is believed to set the tone for the coming year. Activities such as visiting a shrine or temple for hatsumode, the first shrine visit of the year, are common, with major shrines like Tokyo's Meiji Shrine attracting millions of visitors.

Shōgatsu is also characterized by specific foods and decorations. Homes are adorned with ornaments made from pine, bamboo, and plum trees. Traditional dishes like osechi ryōri, served in lacquered boxes, and zōni, a soup containing mochi, are enjoyed over the first three days of the New Year. These foods are imbued with various symbolic meanings, representing wishes for good fortune and prosperity.

Despite the modern influences, Shōgatsu retains many traditional elements that have been celebrated since ancient times, some dating back to the 6th century. This blend of old and new customs ensures that Shōgatsu remains a deeply rooted cultural event, reflecting both historical continuity and the adaptations of contemporary Japanese society.

The Treasure Ship (Takarabune), 1840, © Utagawa Hiroshige via Wikipedia.

Themes and Symbols in Shōgatsu

Shōgatsu, the Japanese New Year, is a celebration rich in tradition and symbolism, reflecting the cultural values and beliefs of Japan. This festive period is marked by a variety of customs and practices that embody themes of renewal, family unity, and good fortune. From the preparation and consumption of special foods like osechi-ryōri and zōni, to the ringing of temple bells and the exchange of nengajō postcards, each tradition carries deep significance. Symbolic elements such as mochi, Takarabune, and otoshidama envelopes further enhance the festive atmosphere. Through poetry, games, and communal activities, Shōgatsu weaves together a tapestry of customs that highlight the rich cultural heritage and the hope for prosperity and happiness in the coming year.

Traditional Food: During Shōgatsu, food plays a central role, with several traditional dishes being served that are rich in symbolism and history. One of the key components is osechi-ryōri, a collection of specially prepared New Year's dishes. These dishes, often sweet, sour, or dried, were originally designed to be preserved without refrigeration since stores were closed during the holiday period. The variety in osechi can differ significantly by region, with some foods being considered auspicious in certain areas while viewed negatively in others. Another significant dish is zōni, a soup featuring mochi (rice cake) and other ingredients that vary regionally. On New Year's Eve, it is customary to eat toshikoshi soba, buckwheat noodles symbolizing longevity. Contemporary celebrations often include sashimi and sushi, and even non-Japanese foods. To give the stomach a rest after the festivities, nanakusa-gayu, a seven-herb rice soup, is prepared on January 7, known as jinjitsu.

Mochi: Mochi, a sticky rice cake, is another important element of Shōgatsu. Traditionally, mochi is made by pounding steamed sticky rice (mochigome) in a wooden container called an usu, a process that requires teamwork and rhythm. Mochi is consumed during the New Year period and is also used to create kagami mochi, a decorative mochi arrangement. Kagami mochi consists of two round cakes of mochi topped with a tangerine (daidai), which symbolizes the continuity of generations and good fortune.

Bell Ringing: On the night of December 31, Buddhist temples across Japan perform Joya no Kane (除夜の鐘), where temple bells are rung 108 times. This ritual symbolizes the expulsion of the 108 earthly temptations and desires according to Buddhist belief. The bells are rung 107 times before midnight and once after, representing the old and new years. One notable event is The Watched Night bell in Tokyo, which attracts significant attention.

Nenga: Nengajō, or New Year's cards, are an integral part of Shōgatsu. Similar to Western Christmas cards, these postcards are sent to friends and relatives to convey New Year greetings. The cards are typically mailed in mid-December and are guaranteed by the post office to arrive on January 1. If a family has experienced a death in the past year, they send a mourning postcard (喪中葉書, mochū hagaki) instead. The designs often feature the Chinese zodiac sign of the year, and addressing the cards by hand is a common practice. Despite the rise of digital communication, nengajō remains a popular tradition, especially among older generations.

Otoshidama: A beloved tradition for children during Shōgatsu is otoshidama, where adults give money to children in decorated envelopes called pochibukuro. This custom has roots in the Edo period when wealthy families would give mochi and mandarin oranges to spread happiness. The amount of money varies but is typically significant, often exceeding ¥5,000 (about US$50).

Poetry: New Year traditions are also celebrated in Japanese poetry, particularly haiku and renga. These poems often incorporate kigo (season words) related to New Year activities and symbols, such as the first sunrise (hatsuhi), first laughter (waraizome), and first dream (hatsuyume). Traditional activities like writing the first letter (hatsudayori) and performing the first calligraphy (kakizome) are also popular themes in New Year's poetry.

Takarabune: The Takarabune or Treasure Ship, piloted by the Seven Lucky Gods, is a symbolic image during the first three days of the New Year. A picture of this ship is considered essential for good fortune and is a common part of New Year decorations.

Games and Entertainment: Shōgatsu is also a time for traditional games and entertainment. Popular New Year’s games include hanetsuki (similar to badminton), takoage (kite flying), koma (spinning tops), sugoroku, fukuwarai (a game similar to pin the tail on the donkey), and karuta (Japanese playing cards). The television show Kōhaku Uta Gassen, where popular music artists compete in red and white teams, is a staple of New Year's Eve entertainment.

Sport and Music: Sporting events and music also play a significant role. The Emperor's Cup final, a national football tournament, is held on New Year’s Day, and mixed martial arts organizations host events on New Year's Eve. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is traditionally performed throughout Japan during the New Year season, a practice that has become deeply rooted in Japanese culture since World War I.

Little New Year: While Shōgatsu primarily focuses on the first few days of January, there used to be an associated festival called Little New Year (小正月, koshōgatsu), traditionally held on the 15th day of the first lunar month. This festival included rites for a bountiful harvest and the burning of New Year decorations in a ceremony known as Sagichō or Dondoyaki.

In contemporary Art

In contemporary Japanese art, Shōgatsu continues to inspire a wide array of creative expressions that blend traditional motifs with modern sensibilities. Artists often incorporate themes and symbols from the New Year celebration into their work, using elements like mochi, Takarabune, and the iconic kagami mochi in various forms of visual art, from paintings to digital media. The vibrant hues and intricate designs of nengajō (New Year postcards) have also found their way into contemporary graphic design, reflecting the fusion of age-old customs with current trends. Performance arts, including theater and music, frequently feature New Year’s themes, celebrating the cultural significance of Shōgatsu through innovative interpretations.

The influence of Japanese art on Western artists spans centuries and has left an indelible mark on various movements and styles. Beginning with the Impressionists in the late 19th century, Western artists were captivated by the aesthetics of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which depicted scenes from everyday life in Edo-period Japan with flattened perspectives and bold compositions. Claude Monet's fascination with Japanese bridges and gardens, echoed in his Water Lily Pond series, demonstrates a clear adoption of Japanese compositional techniques and themes. Similarly, Mary Cassatt integrated the flat colors and simplified forms of ukiyo-e into her intimate portrayals of women and children, as seen in works like The Coiffure. Moving into the 20th century, artists like Gustav Klimt embraced the decorative elements and gold leaf backgrounds reminiscent of Japanese Rinpa school aesthetics, evident in his iconic Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Even Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock drew inspiration from Japanese calligraphy, incorporating its rhythmic energy and gestural marks into their groundbreaking canvases. Today, the influence persists in contemporary art, particularly through the global popularity of manga and anime, as seen in the works of artists like Takashi Murakami, who bridges traditional Japanese motifs with modern pop culture. This enduring cross-cultural exchange continues to enrich Western art with new perspectives and techniques, ensuring that Japanese art remains a dynamic force in the global artistic landscape.

Nataliya Lesnykh's, Lion Dance. Kabuki., 2020. Painting, Oil / Acrylic / Marker on Canvas, 137cm x 86cm.

Nataliya Lesnykh's painting Lion Dance. Kabuki. (2020) vividly captures the essence of Japanese Kabuki theater through a mesmerizing blend of oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas. The artwork portrays the intense Kabuki dance known as Kagamizishi, featuring a male warrior embodying the fearless spirit of a white lion. The artist skillfully depicts the transformation of a fragile and shy girl named Yayoi into the lion character through meticulous detail in the costume, mask, and physical expression. The painting resonates with themes central to Shōgatsu, such as strength, endurance, and the pursuit of perfection through performance arts—a reflection of the cultural and spiritual dimensions celebrated during Japan’s New Year festivities.

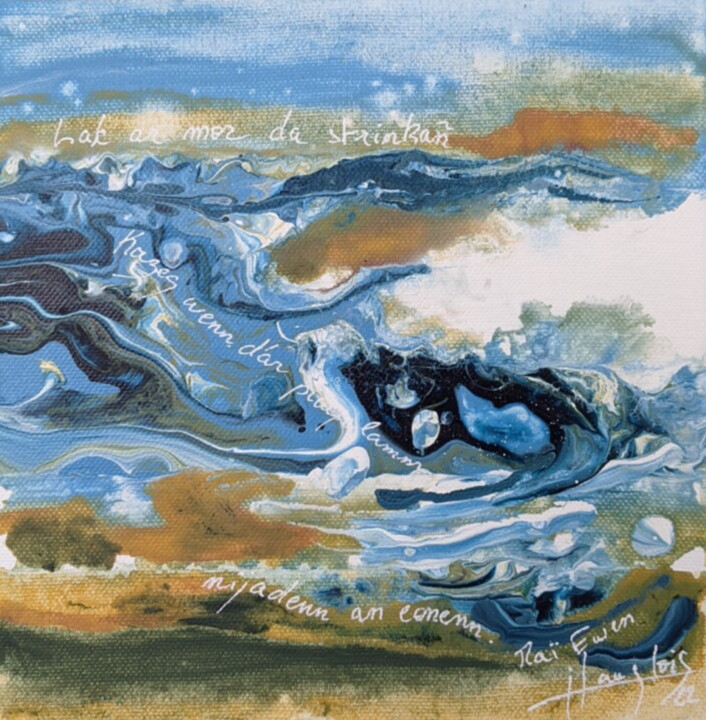

Isabelle Langlois, Lak ar mor, 2023. Painting, Acrylic on Canvas, 20cm x 20cm.

Lak ar mor (2023) by Isabelle Langlois is an acrylic painting on canvas that embodies the essence of Haïga, a fusion of haiku poetry and visual art practiced in Japan. Collaborating with a Breton poet dedicated to preserving the Breton language through haiku, Langlois translates these poetic verses into vivid imagery. The artwork reflects themes of cultural preservation and transmission, resonating deeply with the spirit of Shōgatsu. Just as Shōgatsu emphasizes traditions passed down through generations, Lak ar mor symbolizes the continuity of cultural heritage and the timeless beauty found in nature, echoing the reverence for natural cycles and renewal inherent in Japan's New Year celebrations. Langlois' artwork thus bridges the cultural landscapes of Brittany and Japan, illustrating how artistic expression can transcend borders and evoke shared themes of tradition and renewal during festive occasions like Shōgatsu.

Ella Joosten, Hagoita One, 2012). Painting, Acrylic / Oil on Canvas, 130cm x 90cm.

"Hagoita One (2012)" by Ella Joosten, an acrylic and oil painting, captures the essence of a traditional Japanese New Year custom, the hagoita. The painting, characterized by Joosten's figurative and impressionistic style, portrays the intricacies of this cultural artifact. In Japan, hagoita, or lucky dolls, are placed in homes on New Year's Day to usher in happiness for the coming year. These ornate paddles are often blessed by temple priests and later burned in gratitude at year-end, symbolizing renewal and the cyclical nature of time. Joosten's artwork not only celebrates the visual beauty and cultural significance of the hagoita but also evokes themes of tradition, renewal, and the festive spirit observed during Shōgatsu, aligning with Japan's reverence for ritual and symbolism during the New Year celebrations.

Japanese art encompasses a rich tapestry of styles and media, spanning millennia from ancient times to the present day. Rooted in traditions that began in the 10th millennium BCE, Japanese art evolved through periods of isolation and cultural exchange, each phase leaving a distinct imprint on its artistic landscape. From the serene beauty of ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper to the vibrant ukiyo-e woodblock prints of the Edo period, and from the intricacies of origami to the meticulous craftsmanship of bonsai, Japanese art reflects a profound connection to nature and a keen appreciation for aesthetics. With the advent of modernity in the Meiji period, Western influences catalyzed new artistic expressions, leading to a fusion of traditional techniques with contemporary themes. Today, Japanese artists continue to push boundaries in global contemporary art, exploring diverse mediums such as animation, video games, architecture, and installation art, while also embracing and reinterpreting their rich cultural heritage. Artists like Takashi Murakami and Yayoi Kusama exemplify this dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation, cementing Japan's enduring influence on the global art stage.

Shōgatsu, the Japanese New Year, stands as a vibrant tapestry woven with deep cultural significance and rich symbolism. Rooted in centuries-old traditions, Shōgatsu reflects Japan's reverence for renewal, family unity, and the pursuit of prosperity. From the solemn ringing of temple bells to the joyous exchange of otoshidama envelopes, each custom carries profound meaning, encapsulating hopes for the future and respect for the past. The culinary delights of osechi-ryōri and zōni, alongside artistic expressions like kagami mochi and Takarabune, further enrich the festive atmosphere, ensuring that Shōgatsu remains a cherished celebration that bridges generations and honors Japan's cultural heritage. As contemporary Japanese art continues to evolve, drawing inspiration from these timeless themes, Shōgatsu's enduring legacy persists, fostering a sense of community and renewal that transcends borders and resonates throughout the global artistic landscape.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei