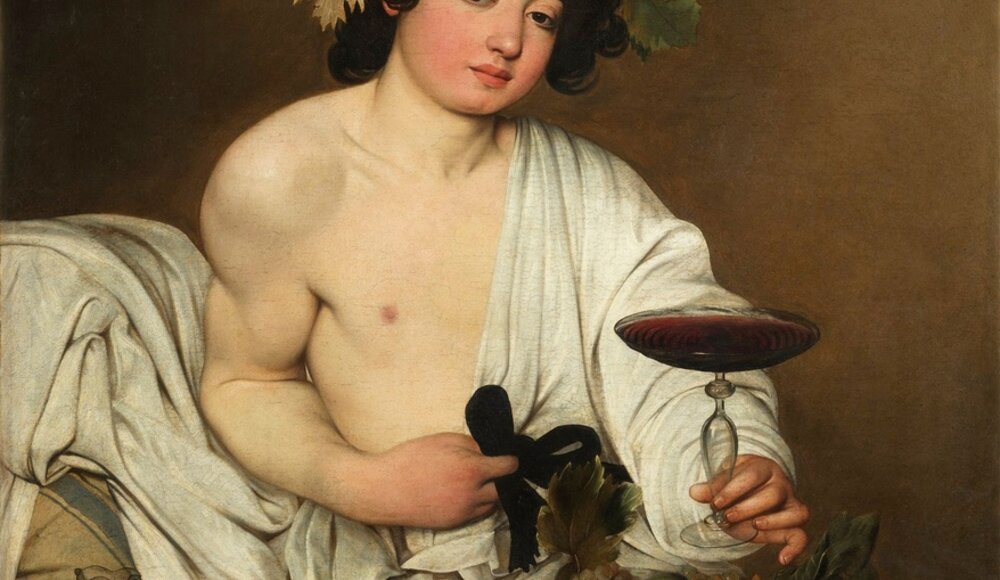

This oil painting of 37x33 in (a relatively common size for the time) depicts a young androgynous man in the guise of the famous Bacchus. Roman equivalent of Dionysus, he's the god of wine and excess, of carnal pleasure and extravagance. Surrounded by a white drapery that gives a glimpse of a torso as sensual as athletic, the man hands us a glass of wine in his left hand, and only the ribbon surrounding his toga, held in his right hand, separates us from his complete and total nudity.

Caravaggio, Bacchus, circa 1593. Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Caravaggio, Bacchus, circa 1593. Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Around him, a string of symbols refers us to his fundamental nature: we perceive first a pitcher of wine with strange reflections (a hidden self-portrait?), then a basket of fruits, some of which appear moldy (but why?). Finally, the character is wearing a magnificent vine crown on his head.

A singular historical context

Shrouded in mystery and uncertainty of all kinds, specialists have difficulty agreeing on the origin of this artwork. It is considered to have been painted at the end of the 16th century (between 1593 and 1600 according to experts): it’s a youthful artwork by Caravaggio (he was between 22 and 29). Although early, this luminous painting already shows remarkable technical qualities.

According to specialists, it was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, who wished to offer the painting to Ferdinando I de' Medici (Grand Duke of Tuscany) for a very special occasion: his son's wedding. The known provenance of the artwork attests to its presence in the prestigious Medici collection: this arrogant young Bacchus was already a star only a few years after his birth.

Entourage of Alessandro Allori, Ferdinando I de' Medici, 1588. Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Upon the death of the last heiress (1743), the illustrious Medici Collection was bequeathed to the city of Florence, which created a dedicated museum for the occasion: the Uffizi Museum, now world-renowned for its rich galleries. Forgotten in the storerooms, this young Bacchus was only rediscovered in the 20th century by two particularly persistent experts. The artwork was abandoned in a lamentable state: it was found on the floor of a dark and damp storeroom. It’s scratched and completely yellowed, but the studies are formal: it’s definitely a Caravaggio.

Today, this divine portrait is one of the most famous paintings by the Italian master. It’s the second known representation of Bacchus by the artist, as there is another one - The Young Sick Bacchus - on display in the Borghese Gallery in Rome.

Caravaggio, Young Sick Bacchus, 1593-1594. Galleria Borghese, Rome (Italy).

Why is it a Masterpiece?

Apart from its invaluable technical and aesthetic qualities for its time, this artwork brings together two important elements, both for Caravaggio and for the Art History in general:

A still life

Caravaggio, Bacchus (details). Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Caravaggio was one of the precursors of the genre. At the time, still lifes as we conceive them today already existed, notably thanks to the fundamental work of Fede Galizia (a woman, yes!), but they were so rare that they didn't really interest patrons and collectors, who preferred more traditional formats: mythological scenes or bourgeois portraits. Here’s a real effrontery from the artist, who, by this aesthetic addition, sheds new light on this stylistic exercise that will soon become legion among artists all over the world.

Fede Galizia, Peaches in a Glass Bowl with Quinces and a Grasshopper, 1610.

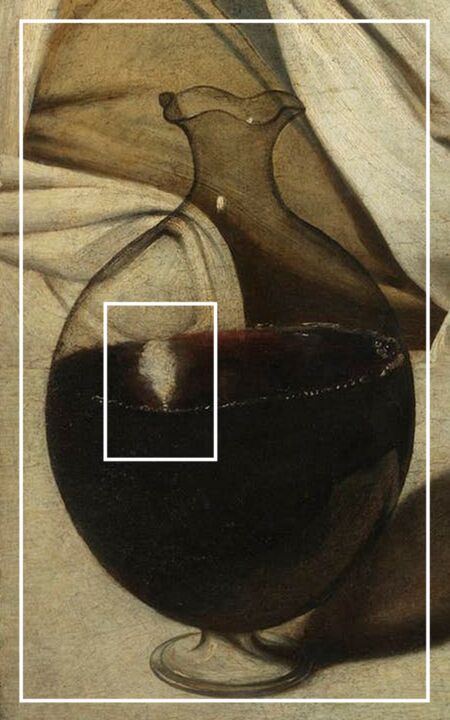

A potential hidden self-portrait

For many art historians, a self-portrait of the artist is hidden in the reflection of the wine carafe in the foreground of the artwork. It’s hard to see with naked eye: successive restorations haven't spared it. However, X-ray analysis shows that there’s a silhouette in this strange reflection.

Caravaggio, Bacchus (details). Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Concealed self-portraits are a godsend for the Art History: following Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (1434), and preceding Diego Velasquez's Las Meninas (1656), this painting is one of the masterpieces recognized for the original audacity of their author. Indeed, before the emergence of modern art, self-portraits were (very) rare: no patron desired to buy an artist's portrait, and these painters' exercises flirted dangerously with egocentrism, in a climate gangrenous with religious dogma. We were then far from a #Selfie Generation, and if you’re interested in the subject, feel free to read our article on the 8 Most Famous Self-Portraits in Art history.

Care for details

Let's focus now on the allegorical character of the artwork. As we mentioned above, it isn’t a direct and unequivocal representation of the god Bacchus, but rather a young man with his characteristic features. But how can we determine the difference? How does one arrive at this conclusion?

Caravaggio, Bacchus (details). Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

Here, the artist has given us several details that suggest he isn’t the god himself. Stay tuned, it's fascinating! Already, we can observe that under the white drapery covering part of the young man and the bench is another pattern: it’s a dull, worn fabric with a blue line. There’s no doubt that this is a contemporary ornament, which has no place in a mythological representation intended to be authentic.

Then, a careful reading of the artwork will make you notice that the hands of the aesthete are dirty, his nails are dark, as if they were earthy. This detail is a classic symbol of peasant iconography, when painters want to highlight the proletarian origin of a protagonist. No god cultivates the land, not even the god of the vine. In the same spirit, the variations of colors on the face and hands of this supposedly divine character testify to his real nature: the gods aren’t subjected to redness, these skin weaknesses are reserved for humans. Caravaggio hated idealization, even when he had to paint divinities.

Caravaggio, Bacchus (details). Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

An Allegory of Life

Finally, and this is certainly the main information to be retained from this painting: it underlines (subtly once again) the passage of time and the evanescence of sensual pleasures.

Some fruits are painfully maintained in a state of advanced maturity: we see a brown apple in the foreground, a pomegranate bursting next to it, then another apple, worm-eaten this time, as well as several reddened leaves, symbols of the decline of the seasons, and cycle of life.

Caravaggio, Bacchus (details). Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Italy).

These tired fruits easily evoke the classic mantra of the vanities: "Memento Mori", remember that you will die. Caravaggio didn’t paint unappetizing fruit for the simple pleasure of spoiling a canvas that could have been sumptuously decorated with colorful and juicy fruit: he wanted to make us meditate on the passage of time, on the insignificance of our lives in the face of the ineluctable countdown of life.

According to the art critic Alfred Moir, we must perceive a discreet moral, "because if the boy triumphs in the splendor of his youth, it will vanish as quickly as the bubbles in the carafe where we have just poured the wine.”. The artist invites us to enjoy our youth before everything disappears.

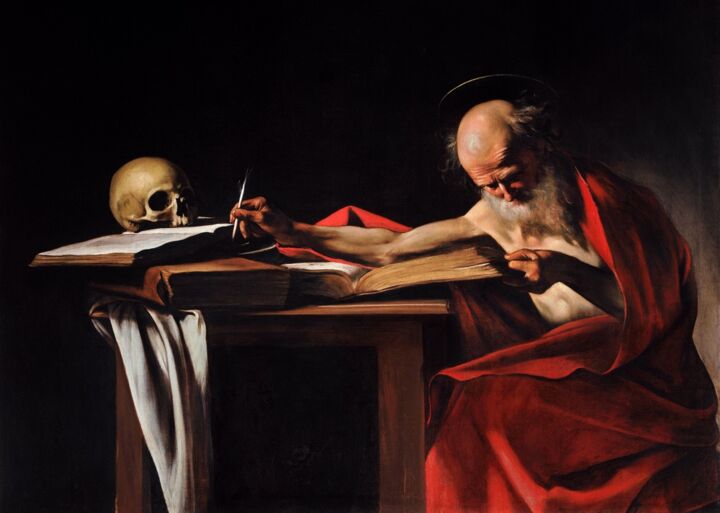

Caravaggio, Saint Jerome Writing, circa 1605. Galleria Borghese, Rome (Italy).

Subtly but surely, Caravaggio offers us one, then two, then three ways of reading a single artwork throughout his entire career. Sometimes these analyses contradict each other, sometimes they complement each other, but it’s always fascinating. Hats off to the artist!

Discover here our Artwork Selection inspired by Caravaggio.

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)