Salvador Dalì, The face od war, 1940. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Why do we enjoy scaring ourselves?

To answer the question posed in the title, we can refer to the certainty of science, a discipline that has made it known that when we experience fear, the amygdala activates rapid and primitive reactive modes. These, combined with hormones ready to promote a state of alertness, can increase insulin production and blood sugar levels, as well as make our breathing more labored, our hearts beat faster, our pupils dilate, and make us feel constantly on edge, as if we were always ready to flee. In reality, however, it is important to note that the hormones released in the aforementioned situations, including endorphins and dopamine, which, in case of emergency, should alleviate pain, also contribute to the experience of pleasure and excitement, intrinsically linked to a circumstance of proximity to danger.

Therefore, the success of Halloween, but also, for example, of more common horror films, lies in the fact that the aforementioned state of enjoyment can be safely experienced, as it does not involve any actual danger, since the scare is, for the occasion, clearly simulated. So, now that we've unveiled the connection between fear and pleasure, I would like to entertain you by offering a tale of terror, narrated by some masterpieces in the history of art, which, when viewed one after the other, could actually build a Halloween-themed story.

Théodore Géricault, The Severed Heads, 1818.

Théodore Géricault, The Severed Heads, 1818.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1620. Oil on canvas, 158,8×125,5 cm. Napoli, Museo azionale di Capodimonte.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1620. Oil on canvas, 158,8×125,5 cm. Napoli, Museo azionale di Capodimonte.

Scaring with art...

Once upon a time, and by that I mean I don't know where or when, there was a solitary figure without a human face, with decidedly imposing and frightening features. Its dark and wrinkled skin expressed an enigmatic expression of pain mixed with despair. I hope that your skin can now crawl, and that a drop of sweat is ready to run down your forehead, at the mere thought of facing the unidentified being in question, which, inside its two eye sockets and mouth, contains two skulls, which, in turn, have additional deathly figures in their cavities. Completing this adrenaline-inducing vision is the presence of the ultimate symbol of sin, the snake, unmistakably linked to Lucifer's realm, which, in several specimens, inflicts pain on the face in question, making it taste the blades of its teeth.

As I mentioned earlier, this is not the set of a horror film, but a masterpiece of art history, namely Salvador Dalí's "The Face of War" (1940), conceived to frighten man in the face of a sad reality of his existence: the continuous and eternal threat of war. The terrifying tale of art could continue, becoming even darker, by quoting Théodore Géricault, who, too, was "passionate" about gruesome heads, as evidenced by "The Severed Heads" (1818). The work in question is even more impressive in that it depicts, against a black background and in semi-darkness, two severed human heads, which, lying like still life on a cloth, make the viewer touch his neck to ensure that his head are still firmly attached. In addition, it is worth noting that the tale of terror can in this case go beyond the nature of the subject matter and extend to the manner of execution, as it is known that the artist set up his studio near the hospital, delighting in observing the sick, the dying, and the corpses, to the extent that some speculate that he even had the "habit" of keeping pieces of human bodies in his studio, sometimes taken from the "theater" of beheadings.

This latter gruesome, bloody, and frightening event is ready to terrify us in the image of the most famous beheading in art history, which, to scare you, I will first describe, and only later reveal in the title and the author. A man, intoxicated after feasting, finds himself naked and lying on a bed, believing he can lie with a beautiful maiden who is favorable to him. However, the amorous encounter turns into a bloodbath, as the young woman in question, after robbing him of his sword, proceeds to slit his throat, aided by a servant who holds the soldier's arms. It is precisely this last violent scene that has been captured on the canvas, leaving the viewer petrified as they watch the beheading, focusing on the final moments of the male face's existence and the sword piercing his neck, generating streams of blood ready to spatter the air and stain the mattress.

Broadening the gaze progressively, the "background" to this portrayal of death is provided by the hands of the two women, subsequently identified in their faces ready to reveal the energy expended in the fatal effort. If you are now afraid to return home to your wives, perhaps I have achieved the purpose of my story, even though, in reality, the scene of domestic violence in question is part of the iconic "Judith Beheading Holofernes" (1620) by Artemisia Gentileschi, a work where the mechanism of revenge against male oppression is evident, stemming from the episode in which the Italian painter was raped by her colleague Agostino Tassi. Moving from beheadings to more modern "punishment" techniques, we can finally arrive in the mid-1960s, imagining that we see in front of our eyes an empty electric chair, placed in a bare room, with a small wooden table and a sign that reads "silence."

The light placed in the empty space on the floor, right in front of the chair, almost seems to invite us to take a seat, causing us to forget about the danger of the context, to the point of trapping us forever. These are my impressions regarding the last terrifying work analyzed, namely "Electric Chair" (1964) by Warhol, a masterpiece that is part of the terrifying "Death and Disaster" series, rich in subjects inspired by tragedies such as car accidents and suicides illustrated in newspapers. In this context, Andy wanted to demonstrate how when one sees a horrific picture over and over again, it actually loses its effect, a concept that could be reused to reread my narrative, proving quite impassive to the inexorable repetition of the terrifying concept of death. Finally, the tale, perhaps now no longer frightening, continues in the works of Artmajeur artists that follow, such as those of Vaxo Lang, Hanna Melekhavets, and Bryah.

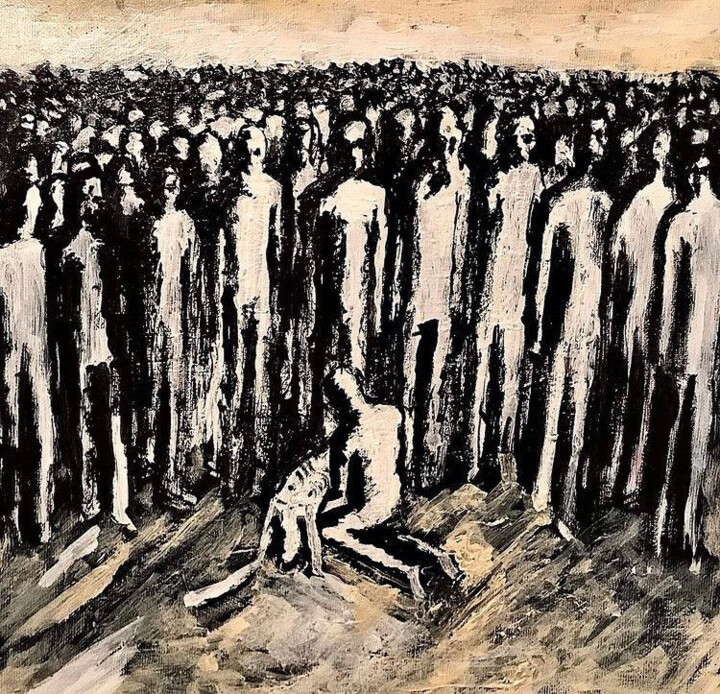

DEATH AND SPECTATORS (2021)Painting by Vaxo Lang.

DEATH AND SPECTATORS (2021)Painting by Vaxo Lang.

"DEATH AND SPECTATORS" by Vaxo Lang

The iconography of the Pietà was initially created using a rigid framework, in which the upright figure of Mary contrasted with the horizontally stiffened body of Christ, a well-rendered portrayal, as seen, for example, in Perugino's Pietà. However, following Michelangelo's influence, the figure of Jesus was innovatively depicted gently lying on the Virgin's lap, bringing an extraordinary naturalness to the scene, aimed at uniting the two characters in a moment of touching intimacy. Vaxo Lang, an artist from Artmajeur, embraces the lessons of the Italian master, bringing further flexibility to the depicted dying body, now observed by a rich crowd of spectators, who gather infinitely within a landscape defined only by the sky. The expressionist work in question reveals, through its explicit title, its main intent: to "celebrate" death as a knowledge event, one to attend to become more aware. Regarding the artist in question, Vaxo Lang, born in 1993 and originally from Tbilisi (Georgia), appears to be quite fascinated by themes related to departure, which he often connects to rather introspective viewpoints, capable of merging physical and mental suffering.

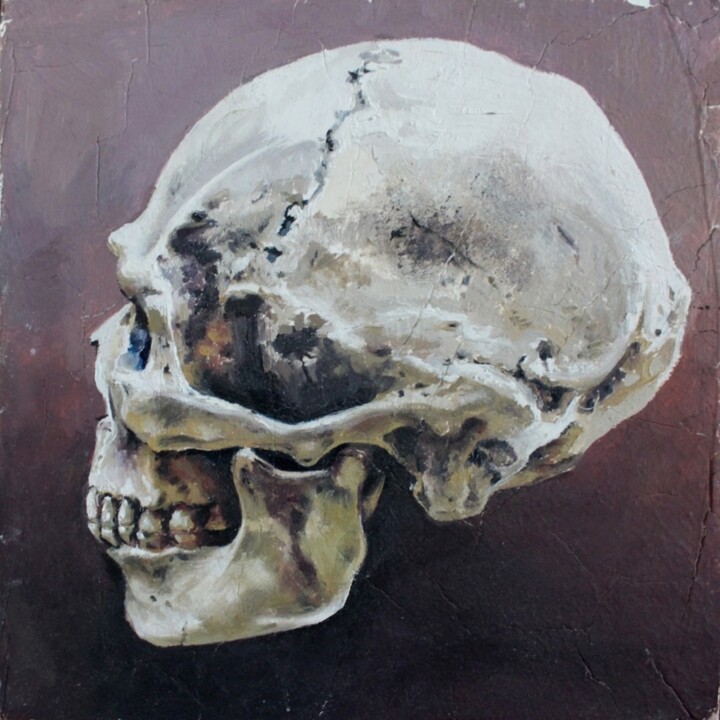

"SKULL" by Hanna Melekhavets

On the canvas, there is only a close-up of a skeleton, whose anatomy is well defined by chiaroscuro, delving into the cavities of the skull bones with hues ranging from blue to brown to black. The subject in question is presumably lifeless, which reminds us of the more "lively" specimen created by Van Gogh, captured while smoking a cigarette in the masterpiece titled "Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette" (1885-86). This small-sized work probably dates back to the winter of 1885-86, a period when it was conceived to criticize more conservative and "boring" academic practices, including the traditional study of skeletons to understand human anatomy, which the artist ironically dismissed by lighting a cigarette. As for Hanna Melekhavets, the contemporary painter based in Poland demonstrates a strong commitment to traditional techniques and languages, aimed at reflecting on existence as well as the world, the infinite, and the balance between opposites.

THE DEATH (2022)Photography by Bryah.

THE DEATH (2022)Photography by Bryah.

"THE DEATH" (2022) by Bryah

The artist from Artmajeur states that he depicted death for these reasons: "It is starting from death as a starting point that humanity has forged rules, beliefs, and conceptions, such as those of hell, paradise, limbo, the abyss, or any other term one chooses to use. Inspired by this concept, I created a series of images, including this one in particular, titled 'The Death,' which captures the morbid aspect of death, its dark and cold essence, the fear of dying." At this point, I feel it is important to clarify how the death in question can actually take on the peculiarity of life itself because it is precisely the fear of the end that drives us to create in order to remain on Earth forever. A famous example of the juxtaposition of death and vital artistic creation, which has made the features of its creator immortal, is Arnold Böcklin's "Self Portrait with Death Playing the Violin," a work that depicts the painter with a palette and brush in hand, interrupted by Lady Death who imposes her presence by playing a violin with only one string. This detail serves to evoke the Greek myth of the Fates, goddesses who indeed had the task of spinning and cutting the threads of men's lives, as if it were a thread.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli