0023 (2021)Drawing by Hiperblackart.

0023 (2021)Drawing by Hiperblackart.

There are several ways to talk about the art of drawing, such as illustrating the origin of its technique by explicating its evolution, or showing in chronological order works that changed its history, finally, placing the narrative in a precise time frame, to let the work of the major exponents of the era in question speak for itself, just as if we were to take Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael as our models to tell the story of Renaissance drawing. With regard to the latter, introducing the topic in a more general way, that is, without yet mentioning the aforementioned geniuses, it is good to highlight how during the Renaissance, the aforementioned artistic technique was mainly used for a utilitarian purpose: that of serving as a prolific time to devote to the elaboration of artistic ideas, which were developed, perhaps, at a later stage. This practice, known as preparatory drawing, became extremely necessary for artists, who wanted to prepare for an upcoming commission or composition. Within this artistic externalization, actual drawing and invention were distinguished, the former to be regarded as the ability to create harmonious and proportionate figures, the latter understood as the element of pure innovation in the presentation of an image, ready to evoke the imaginary and the unknown, as well as to give new form to conventional iconography, experimenting, for example, with novel perspectives. Invention and drawing aside, in Renaissance art we can generally encounter four types of drawing: preliminary (sketch), from life, models and cartoons, and the transfer drawings. Regarding the former, it is good to highlight how Renaissance artists made sketches, in which, imagining a future subject to be treated, they gave life to figures with gestural effectiveness, devoid of minute muscular contours and precise proportions, giving weight to expressiveness and the relationships between the elements of the composition. Drawing from life, on the other hand, was used to study the specific poses assumed by living figures, while models and cartoons were finished, formal drawings that the artist shared with the commissioner for the realization of a specific commission. Finally, precisely many finished cartoons were used between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to transfer the drawing to the surface that would contain the finished work. Turning now to the account of drawing through its most important Renaissance exponents, it is obligatory to speak first of all of Leonardo da Vinci, and then to proceed to Michelangelo and the younger Raffeallo. Of the first master in question, it is necessary to make it known how he, who was quivering to know the world around him through reason, relied on the scientific model, investigating precisely through the technique of drawing, which is to be understood as the most immediate representation of idea and thought. In this context, what has been said is well exemplified by the drawing of the catapult, a mixture of art, practicality, science, engineering and imagination, which, created using an ink pen on paper, represents a sketch of the ancient war machine accompanied by explanatory notes, aimed at transforming a work of art into a drawing designed to be concretely used. In fact, such ink hints at how the device would have worked, through the use of some levers, gears and weights made of wood, perhaps with the addition of some metal elements, functional for throwing stones at long distances.

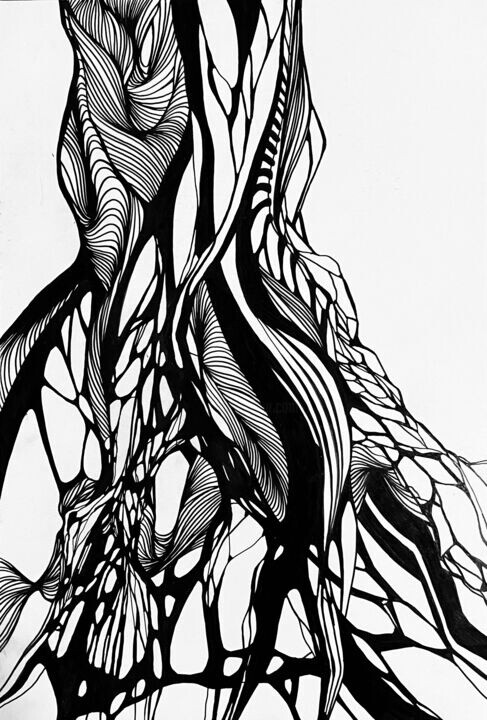

CONVERGENCE OF RANDOM VARIABLES (2019)Drawing by Marco Paludet.

CONVERGENCE OF RANDOM VARIABLES (2019)Drawing by Marco Paludet.

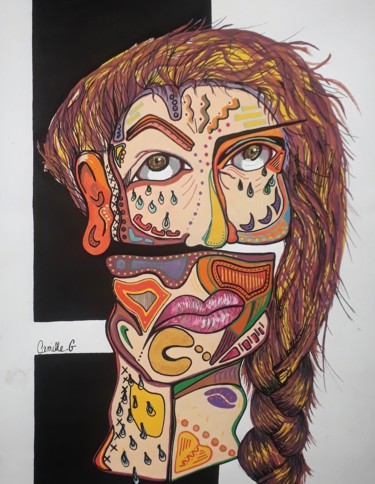

OFFICIUM (2021)Drawing by Karen David.

OFFICIUM (2021)Drawing by Karen David.

After Leonardo it is the turn of Michelangelo, whose extraordinary draftsmanship was made available for such diverse disciplines as fresco, architecture and sculpture, techniques in which his sketches would have been the first and main point of reference. Generally Michelangelo's drawings appear unfinished, so much so that they appear to be functional only for the production of the main work, as only on a few occasions were they also realized in detail, which, by transforming them into complex works, created compositions that the master used to give as gifts to friends and colleagues. An example of the drawing of the Tuscan genius is Il sogno (The Dream), one of the best-known drawings of the Italian Renaissance, whose meaning, enigmatic and elusive, is probably to be connected with the dream world, rendered through the depiction of a winged spirit, swooping down to bring a message to a naked young man, intent on resting the upper part of his figure on a globe, which finds its place above a box containing enigmatic masks. Forming the background of this composition are several groups of twisted bodies, which are lost in the fumes of a rather murky haze. In this context, the main figure of the nude could be interpreted as the personification of human consciousness, awakening from a dream, to devote itself to virtue by renouncing vice, perhaps represented by the multiple figures in the background. Finally, other symbols would seem to be the sack of money, allusive to avarice, and the masks, emblems of deceit and lies. The result is a work capable of testifying to Michelangelo's exceptional skills as a draughtsman, an artist capable of creating complex and powerful compositions, in which flesh is shaped with almost invisible strokes, defined with firm contours, ready to evoke the miracle of sculptural art. Finally, the last master in question is Raphael, an artist, who, referring to the words of Giorgio Vasari, studied a great deal, experimenting with innovative compositions, precisely through the medium of drawing, a technique that during the Renaissance was recognized as an autonomous art form and thus also commercialized like paintings. Nevertheless, Raphael continued to conceive of drawing as a finished work only in a few exceptional cases, exploiting it mostly for utilitarian purposes, that is, as a model for later creative development, to be realized exclusively in painting, be it fresco, canvas or panel. An example of the Italian master's drawing is Giovane donna seduta al parapetto di una finestra e altri studi, di figura e architettonici (1511-1514), a work preserved in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi (Florence), in which a striking female figure, positioned as per the title, is accompanied by the study of angels made for the fresco with the Apparizione di Dio a Mosè (Apparition of God to Moses) in the vault of the Stanza di Eliodoro (Heliodorus Room) in the Vatican and architectural sketches. Italian geniuses aside, the narrative on drawing in art history continues through the work of Artmajeur artists such as: Alexander Boytsov, Philippe Alliet and Francesco Marinelli.

BLACK. METAMORPHOSIS. ABSTRACTION (2021)Drawing by Vesta Shi.

BLACK. METAMORPHOSIS. ABSTRACTION (2021)Drawing by Vesta Shi.

BIRTH (2023)Drawing by Alexander Boytsov.

BIRTH (2023)Drawing by Alexander Boytsov.

Alexander Boytsov: Birth

"One more moment and a ray of light will touch you": these are the words with which Alexander Boytsov, artist of Artmajeur, introduces his Birth, a drawing where, as he himself stated, the presence of light, a physical entity capable of constructing, through its presence and absence, sharp and extended shadows, is imposed, in which, in this case, the volumes of the body of a dancer, intent on moving on her toes, while wearing a classic tutu, are well distinguished. Precisely this enhancement of the function of light, brought to my mind some iconic photographs, aimed at making concrete and "tangible" the drawing-brightness binomial: I am talking about Pablo Picasso's "drawings of light," immortalized by the well-known shots of Gjon Mili, a symbol of the brilliant encounter of these two great exponents of twentieth-century art. Retracing the history of the "light drawings" in question, Gjom Mili, an Albanian photographer born in 1904 and an innovator in the field of lighting, visited Picasso in 1949, while the latter was residing in the south of France, a place where the photographer made the painter aware of his latest experiments, aimed at portraying ice skaters, who, having special lights on their skates, moved drawing in the air. The Spanish master, enthusiastic about such a project, proposed the implementation of a similar 15-minute photographic session, which was followed by five sessions, in which he did his best to trace in the atmosphere some sketches in the form of light trails, having as subjects the most popular motifs of his work, including, centaurs, bulls and Greek profiles. The contrast between the darkness and the brightness of the drawing was rendered by the arrangement, within a darkened room, of two cameras, the first used for the side view and the other for the front view.

Philippe Alliet: Rebel horse 032

The competition and dynamism of the "incomplete" horses created by Artmajeur artist Philippe Alliet turns out to be in line with one of the best-known experiments, again with regard to drawing technique, carried out by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. At the same time, Rebel horse 032 stands in stark contrast to a decidedly more static masterpiece by the same master, as well as another made by Leonardo da Vinci. Speaking of the running horse, the French master produced this subject in Sheet of Sketches (c. 1881), a graphite in which a bourgeois maiden proceeds in jumping hurdles astride her steed, intent on jumping in a movement, which is repeated in the momentum of two minute, agile pooches. The dynamism that distinguishes, both Sheet of Sketches, and the artist's ink of Artmajeur, ceases to exist in A Woman and a Man on Horseback (1879-81), a drawing by Toulouse-Lautrec, in which one finds, both the influence of the artist's first master, the sportsman René Princeteau, and the influence of the fashionable figures, which Henri may have observed from the family estate in Albi. Joining the stillness of A Woman and a Man on Horseback is that of Studies of Horses, silver point on blue paper by Leonardo da Vinci, genius who also depicted the mammal in question in a more dynamic way, as is evident in the drawings made in the contexts of battles, as well as in the individual figures of horses and horses and riders.

FRENCH VILLAGE (2023)Drawing by Francesco Marinelli.

FRENCH VILLAGE (2023)Drawing by Francesco Marinelli.

Francesco Marinelli: French Village

Francesco Marinelli's ink on paper, titled French Village, re-proposes a subject dear to the history of art, namely that of the view, which, in the context of small towns, certainly refers back to the example of Rembrandt, author of The Windmill (1641), a work in which he practiced the art of drawing on a metal plate, later corroded by the intaglio process of etching. Technique aside, the 1641 masterpiece, similarly to Marianelli's, depicts the town reality in great detail, although in the Dutchman's work, the boundary between village and countryside is somewhat blurred, as it mainly shows the mill that was located on the bastion De passeerde, situated along the city wall that ran the western limit of Amsterdam. This place, home to the guild of leatherworkers, engaged in the business of softening tanned leather by treating it with cod liver oil, was carefully crafted, so much so that it appears that the work was observed, studied and started from life, and then finished in the studio. Finally, disassociated from the drawing technique are the diagonal streaks in the sky, made by brushing acid on the plate, intended to materialize an atmospheric effect.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli