Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, 1594. Oil on canvas, 94 × 131 cm. Kimbell Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, 1594. Oil on canvas, 94 × 131 cm. Kimbell Art Museum of Fort Worth.

France and Italy, Italy and France

As during the World Cup or the European Championship, spectators take their seats once again to witness the confrontation between France and Italy, cousin countries, yet fiercely competitive with each other. What are they competing for? They have been battling for centuries for supremacy in the world of fashion, design, and the arts in general, although few have had the courage to put this healthy and exciting "fight" into writing so far. Certainly, Italy dominated the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, but it was France that made the most noise between the 19th and 20th centuries. Let the challenge between Italian and French artistic genres begin!

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna of Milk, 1324-25, Siena, Museo diocesano.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna of Milk, 1324-25, Siena, Museo diocesano.

Portrait

Still using the language of football, France takes the ball first, demonstrating its skill in the portrait genre with: Portrait of Madeleine (1800). Marie-Guillemine Benoist's work depicts a servant girl sitting on a chair covered in rich blue fabric, on which she rests her buttocks, showing herself motionless as she stares at us with her arms resting on her belly and on one thigh. She, dressed in white with a tignon on her head, presents her shoulder and right breast uncovered, alluding, both to the fertility inherent in her gender, and to the strong and daring nature of Amazons. Marie-Guillemine now throws the ball to the center, where it is intercepted by an Italian painter, whose task it is to respond by depicting the features of another woman.

Most likely, if I had called in Leonardo da Vinci, with his Mona Lisa or his Lady with an Ermine, not to mention the portraits by the works of Raphael and Botticelli, I would have immediately put the French goalkeeper in trouble, but this was not the case. In fact, precisely because of the detail of the bare breasts mentioned above, it seemed fairer to compare Portrait of Madeleine with the same fertility, which Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Madonna of Milk alludes to. This last panel of more "serious" Gothic style is intended to be much more playful in nature than the French work, as the child, squeezing his mother's puppa to suck her milk, looks mockingly at the viewer. At this point, we remain at zero to zero, aware of two distinctly different ways of painting, as the Italian still proves indebted to the example drawn from Duccio's Madonnas, known for their almond-shaped eyes, elongated profile, tender complexions and fine eyebrows. The French artist, on the other hand, was an interpreter of neoclassical stylistic features, as well as themes dear to history and genre painting.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas, 130.5×190 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas, 130.5×190 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

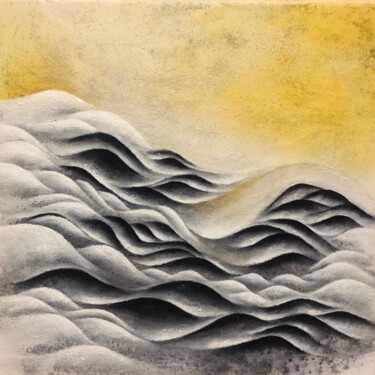

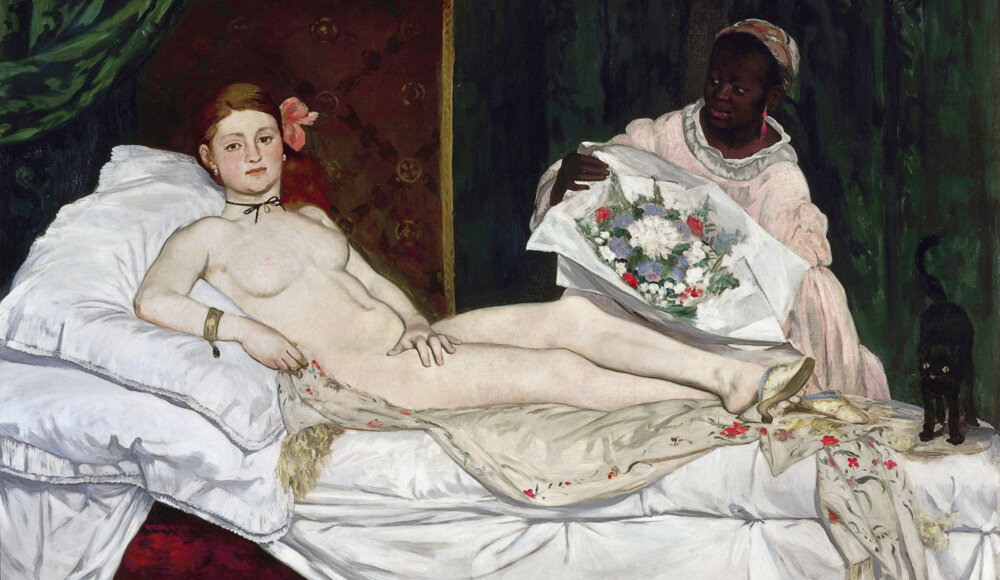

Nude

We are now on a fashion runway, where an Italian designer begins to offer his designs, and on the print of his clothes he quotes a seminal work of the Bel Paese nude painting genre: Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538). The "Dior" in question cleverly responds by quoting Manet's Olympia, one of the French workhorses on the theme. In both cases these are two reclining nudes, in which the woman rests a hand on her pubis, in order to allude to the classical iconography of the demure Venus, although in the Italian case the maiden is a goddess, who was painted for on the occasion of the commissioner's wedding.

In fact, the presence of the roses and the dog send a clear message to the viewer: the beauty of the flower fades away, while the fidelity of conjugal love personified by the animal remains and comforts. Moving on to Olympia, she created a scandal in her day because she poses nude as a goddess despite actually being a harlot. The French master, in fact, innovatively refused to revisit his subject with mythological, allegorical and symbolic filters in order to show a stark naked reality. So, I think, given the innovation of the subject, I will allocate a point to the French team in this case. In any case, retracing my steps about the portrait genre, I award another one to Ambrogio Lorenzetti, given the unprecedented bravado of his Child. As a result: we are now tied again!

Claude Monet, Poppy field, 1873. Oil on canvas, 50×65 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Claude Monet, Poppy field, 1873. Oil on canvas, 50×65 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Landscape

In the challenge between genres also takes over that between related artistic tendencies, since the masters I will discuss are Giovanni Fattori and Claude Monet, exponents of Impressionism, which in Italy was born and spread from the Macchiaioli group. In this case the clash becomes difficult, because I have to take into account that the stylistic features shared by the two artistic practices in question were first born in Italy (with the Macchiaioli), but only became effectively famous later in France, when the Impressionists exhibited together for the first time in 1874. Nonetheless, if I am to immerse myself in the subject of landscape, Fattori's works will be celebrated, but, alas, the Frenchman's fame in the field far exceeds that of the Italian.

So, before describing two works by the masters in question, I will reluctantly confer a point to France. Now, I will briefly mention Monet's Poppy fiel and Fattori's Oxen to cart: The first masterpiece was made in the context of Argenteuil, a small town not far from Paris, where the painter had taken refuge at the outbreak of war, together with his wife Camille and their young son Jean. The latter are also present in the canvas, where they are placed in the likeness of the two figures in the foreground, leaving behind the others scattered in the field of poppies. The painting is simple and rapid, defined by overlapping strokes of color, generating the chiaroscuros rendered through a succession of spots, as well as the red dots in view of the poppies. We move from France to the Maremma, a vast geographical region between Tuscany and Latium, which has always profoundly influenced the painting of Giovanni Fattori, an artist in love with his wild landscapes, which he studied during his long walks in the countryside, jotting down all his observations in a pocket album.

Moreover, it is well known how in this place Fattori had the opportunity to observe the living conditions of the less fortunate and poor, as well as .the dignity with which the peasants faced everyday life. Summing up what has been said is, precisely, one of his most famous works, Oxen to cart, in which the master captures a vast view of the Maremma countryside meeting the sea. Here a pair of white oxen, tied together, pull a wooden cart while a farmer stands, looking ahead, momentarily at rest from his labors. The relentless sun casts its intense glow, enveloping the entire landscape in light. In the foreground, freshly plowed earth and sunburned yellow grass obscure the sea, barely visible beyond the dark bushes. Only the shadows, cast beneath the wagon, suggest that the scene takes place shortly after noon. Adding depth to the desolate sun-drenched vision, a low shady hillside emerges to the right against a sky dotted with light white clouds. The game continues!

Caravaggio, Basket of Fruit, 1597-1600. Oil on canvas, 46×64 cm. Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

Caravaggio, Basket of Fruit, 1597-1600. Oil on canvas, 46×64 cm. Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

Still life and genre scene

The genre of still life and genre scene together constitute a point for Italy, bringing the duel back to parity. This is because Caravaggio, unbeatable in his craft, is involved, as could similarly be the pull of geniuses such as Michelangelo or Raphael. After these assertions Italy feels rather confident, perhaps forgetting that its glory goes back even further than that of France, probably because the Bel Paese, after producing masterpieces in industrial quantities, has shut itself off in a less dynamic exercise of pictorial art, which tends to aim, lazy, at living off what has been. After this sad realization I turn to the great master and his Basket of Fruit, which I will later compare to the French example of Cezanne's Basket of Apples, a painter without whose work, most likely, not even the later Cubism would have existed. But the latter aspect is little cared for by those who appreciate the realism of the Basket of Fruit, the focal point of which lies in the woven wicker basket, inside of which is arranged a variety of fruit, the leaves of which are sometimes desiccated or pierced by insects, intended to remind us of the fragility of human existence.

Naturalistic representation is lacking in the "spots" and "sections" of Cezanne's Post-Impressionist plant pictorial narrative, depicting various objects placed on an improvised wooden platform, among which the presence of apples stands out in number and, in centrality, that of the dark bottle. Having reached this point, it is possible to summarize as follows: one contemplates Caravaggio as one contemplates the real, in Cezanne one gets lost in his interpretation of the latter, understood through a particular way of applying color. Finally, the same argument applies if we take for example two other masterpieces by the masters in question, now belonging to genre painting of the same subject: Cezanne's The Card Players and Caravaggio's The Cardsharps. Now we move on to the conclusion, which will take place by surprisingly introducing sculptural art into our narrative, aimed at comparing Canova and Rodin, artists among the most famous of the medium of artistic expression in question, which will be investigated through the theme of the kiss.

Canova, Cupid and Psyche, 1787-1793. Louvre, Parigi.

Canova, Cupid and Psyche, 1787-1793. Louvre, Parigi.

How Canova kisses, how Rodin kisses

Canova does not kiss. Canova approaches your mouth to contemplate it, to taste and imagine what might happen if he touched it. At the same time, he creates a perfect composition for the realization of the joining of the lips, while the viewers will eternally continue to wonder what shape and taste the intercourse might have. Rodin, Rodin kisses, and protects the act by covering it in the arms of the lovers, who continue to exchange the sweet gesture forever, not fearing the gaze of the envious, but taking affectionate and slow attitudes, far from that of a more eager, voracious and impetuous passion. What I have described you can see for yourself in Canova's Cupid and Psyche and in Rodin's The Kiss, works that closely resemble the essence of the countries that generated it. The Italian makes a spectacle of himself by waving his hands and body, the Frenchman is distinguished but well focused on actually performing the gesture of love, while his cousin is lost in theatrics. I think the game ends, then, with that equality and complementarity that has lasted for centuries.

Now, describing the two works more academically, I start with Canova: Cupid and Psyche depicts, with subtle and refined eroticism, the moment before the two lovers kiss, as foreshadowed by the attitudes of their bodies and the glances they exchange with an intensity of equal sweetness. Love rests his left knee on the ground while, with the thrust of his right leg, he leans forward, arching his torso and simultaneously bending his head to bring it closer to his beloved's face, which he gently supports with his right hand; his left hand, on the other hand, romantically caresses her breast, betraying an undeniable but unspoken desire. In the touch of their hands, marble is transformed into flesh. Psyche, on the other hand, is semi-reclining, turning her face upward and raising her arms almost shyly to welcome Love's kiss, brushing her hair with her fingers as he presents his outstretched wings, as if he has just arrived to rescue her.

Their adolescent bodies, characterized by exquisitely neoclassical anatomical perfection, are completely nude, except for a drape that barely veiled Psyche's intimacy. Here we come now to end with Rodin: originally titled Francesca da Rimini, The Kiss depicts the union of Paolo and Francesca, as narrated in Dante's Divine Comedy, specifically in the fifth canto. In the sculpture, which was originally intended to adorn the left panel of the Gates of Hell, Paolo's body exudes a sense of hesitation with its square, crucial form, while Francesca's body wraps elegantly around his. The contrast between the rough treatment of the rock, marked by chisel and step marks, and the smooth luminosity of the figures, emphasizes the ambiguity of the scene. This ambivalence adds depth to the moment of apparent happiness, infusing it with a deceptive transparency akin to a "blinding clarity" of satanic seduction that leads to an immediate fall.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli