Key Points

- A 10,000-Year Legacy: Japanese art spans millennia, from prehistoric Jōmon ceramics to contemporary digital and conceptual art.

- A Dialogue with Nature and the Spiritual: Japanese art is deeply rooted in nature, Buddhism, and Shinto traditions, balancing ritual with emotion.

- Cultural Crossroads: It has constantly evolved through influences from China, Korea, and the West — especially visible in prints, painting, and design.

- Mount Fuji as Muse: From Hokusai’s iconic Great Wave and Red Fuji to Hiroshi Yoshida’s and Fujishima Takeji’s serene interpretations, Mount Fuji symbolizes both tradition and transformation.

- Ongoing Innovation: Today’s Japanese artists blend tradition, abstraction, and global languages across mediums like installation, photography, and performance.

If the answer is yes, then you should know that the history of Japanese art is one of the most layered, sophisticated, and fascinating in the world. It spans over ten thousand years, moving through periods of cultural isolation and intense openness, moments of religious fervor and centuries of secular aesthetics, ultimately arriving at the contemporary era, where digital art, minimalist design, and the reinterpretation of ancient forms in a modern key coexist.

Japanese art is, above all, an art of dialogue: with nature, with spirituality, with Chinese and Korean influences, and with the modern West. From the Jōmon period (c. 10,000–300 BCE), ceramic artifacts, dogū figurines, and early symbolic forms expressed a sensitivity to the invisible and the ritual. With the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century, artistic production became monumental: bronze sculptures, mandalas, and wooden temples such as the Hōryū-ji became vehicles of faith and instruments of political power.

It was during the Heian period (794–1185) that Japanese art developed its own distinctive style: yamato-e painting, the first emaki (illustrated scrolls), and a form of painting that favored emotional storytelling and subtle color palettes. With the rise of samurai power and Zen Buddhism during the Muromachi period, austere forms took hold—such as karesansui gardens, the monochrome landscapes of Sesshū Tōyō, and an aesthetic of emptiness, suggestion, and rapid gesture.

The flourishing of urban culture in the Edo period (1603–1868) led to the birth of ukiyo-e, the famous multicolored woodblock prints depicting kabuki actors, courtesans, landscapes, and scenes of daily life. It was in this era that Japanese art began to profoundly influence the modern West—just think of Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro, unconscious forerunners of European Impressionism.

Later, from the Meiji Restoration (1868) onward, Japan launched into rapid modernization: art became a space of dialogue between tradition and innovation. Alongside painting influenced by Western academic styles (yōga), the Nihonga movement emerged, reinterpreting classical heritage with a modern sensibility.

In the postwar period, marked by the trauma of defeat and global openness, radical movements emerged: Gutai, anti-art, and later, the global phenomenon of Superflat by Takashi Murakami, which blends manga, pop art, and cultural theory.

Today, Japanese art is a laboratory of global experimentation. Artists like Yayoi Kusama, Chiharu Shiota, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and Yoshitomo Nara combine installation, photography, sculpture, and performance into deep and universal visual languages. At the same time, traditional arts such as bonsai, maki-e, and raku ceramics continue to be practiced and reinterpreted.

Are you truly a lover of Japanese art?

If you’ve read this far, it’s clear that a passion for Japanese art flows through your veins. But do you want final confirmation? Keep reading and let yourself be guided through five essential masterpieces — works that have marked key moments in the history of Japanese art, each shaped by the encounter with the West.

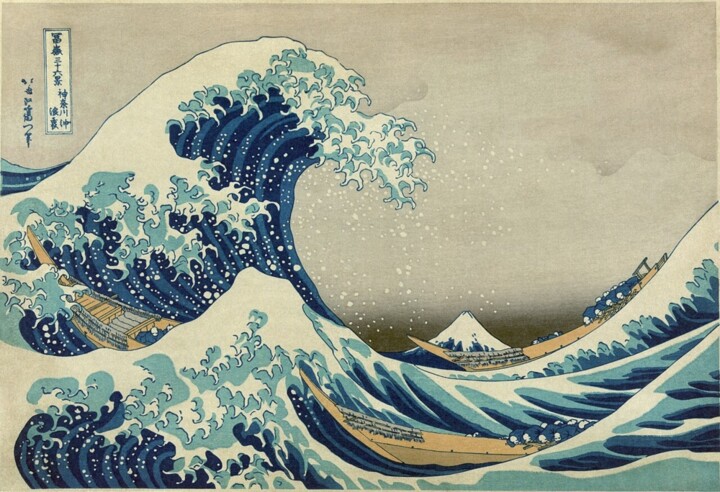

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, ca. 1830-1831. Xylograph in the ukiyo-e style. Various copies preserved in different museums

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, ca. 1830-1831. Xylograph in the ukiyo-e style. Various copies preserved in different museums

1. Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa

If you're a true — and I mean truly true — lover of Japanese art, then you should be able to describe The Great Wave off Kanagawa with your eyes closed. You should know its exact dimensions — 25.7 by 37.9 centimeters — the technique used, ukiyo-e woodblock printing, and perhaps even where its copies are kept today: from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the British Museum in London, with stops in Melbourne, Paris, Turin, Genoa, Trieste, and even Verona.

But since this work is universally known — we might even say it's been overexposed in the global imagination — there's little point in recounting it yet again in a dry, textbook fashion. It's far more rewarding to uncover its hidden folds, the little-known curiosities, and its surprising connections to Western art.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, created by Hokusai between 1830 and 1831, is the first and most iconic image in the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. And indeed, Mount Fuji — Japan’s sacred symbol — sits quietly on the horizon, still and almost shy, while the scene is dominated by a wave that seems like a colossal living creature, poised to devour the tiny boats below. The wave’s motion, its sweeping curve, the visual tension in that split-second before disaster: everything is frozen in an instant of dramatic beauty.

This print is the result of a long gestation. Hokusai had explored the power of the sea and the presence of Mount Fuji in many earlier works. But this particular image, now nearly ubiquitous, was born during a particularly difficult period of his life. He was over 70, widowed, ill, and crushed under the debts inherited from his grandson. And yet, amid the chaos and uncertainty, he created an image that speaks directly to human vulnerability — to the fragile existence of man in the face of nature's overwhelming power.

It’s no surprise that many viewers have seen in this wave a clawed hand, a ghost, a dragon, or an angry deity. Hokusai, who was also a master of supernatural imagery, likely intended to depict not only the physical reality of the sea but also its eerie, metaphysical dimension. Some have even suggested that the wave, with its looming menace, symbolized Japan’s anxiety as it remained closed off from the world, yet increasingly aware of the West pressing in at its borders.

And the West, in fact, is already within this image. The Great Wave is undoubtedly a Japanese woodblock print, but it clearly employs linear perspective — a technique imported from Dutch copper engravings. Mount Fuji, for instance, is depicted small and distant, which would have been unthinkable in traditional Japanese art, where such an important subject would typically dominate the composition. What’s more, the use of Prussian blue — a synthetic European pigment newly available in Japan — lends the print an unprecedented depth and vibrancy. It is an Eastern artwork looking Westward, and perhaps that is precisely why it resonated so powerfully with European artists.

In the latter half of the 19th century, when Japan opened to the world, Hokusai’s wave washed up on the shores of Impressionism. Monet hung it in his studio. Debussy wanted it on the cover of La Mer. Henri Rivière dedicated an entire series to it, The 36 Views of the Eiffel Tower, explicitly inspired by Hokusai. And even today, its visual impact remains undiminished: the shape of the wave, its perfect curve, its jagged foam like fingers or tentacles, etches itself into memory and multiplies endlessly — in emojis, logos, graffiti, watches, advertisements, and illustrations.

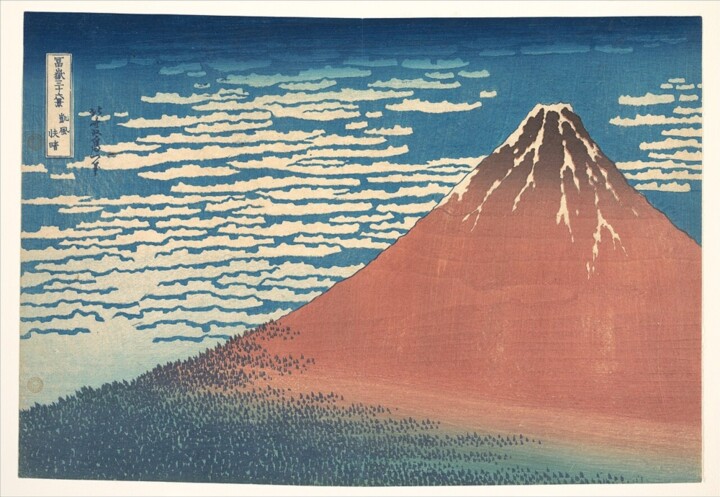

Katsushika Hokusai, Red Fuji, 1830-32.

Katsushika Hokusai, Red Fuji, 1830-32.

2. Katsushika Hokusai, Red Fuji

If The Great Wave off Kanagawa is the dramatic icon of nature’s raw power, South Wind, Clear Sky — also known as Red Fuji — is its perfect counterpart: silent, still, perfectly balanced. Two faces of the same mountain, two opposing perspectives on the majesty of the Japanese landscape.

This print, one of the most celebrated from the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series, is a masterpiece of apparent simplicity. There is no action, no human presence, no boats battling the sea. Just Mount Fuji, immense and solitary, turning crimson at dawn beneath a clear sky swept by a gentle breeze. It’s a real moment: those lucky enough to find themselves near the mountain on a crisp early autumn morning can see it for themselves. The rising sun hits the eastern slope and sets it ablaze with color. In Japanese, it’s called Aka Fuji — “Red Fuji.” Hokusai turned it into an icon.

But behind this surface calm lies a refined symbolic structure. The mountain, perfectly triangular, occupies the right side of the image like a solemn, almost sacred figure. The sparse clouds on the left balance the composition, creating a subtle, almost musical tension. It’s a “timeless” scene, yet full of precise atmospheric detail: the lingering snow on the summit, the dark shadows of the forest at its base, the three distinct shades of blue and red that shape the atmosphere.

The earliest prints of this work are rare and precious: they are marked by a softer, more irregular sky and a restrained use of color, with a delicate Prussian blue halo around the peak. These are known as the Pink Fuji versions — more intimate, less spectacular, but perhaps closer to Hokusai’s original intent. Later, as demand grew, the colors became more intense: the Bengal pink pigment was introduced, clouds were sharpened, the sky flattened, and the green of the forest was recut. Beauty, in this case, comes in many versions.

Curiously, while in the West it is The Great Wave that dominates the cultural imagination, in Japan it is this Red Fuji that is most cherished — almost a talismanic image. According to tradition, dreaming of Mount Fuji is a sign of good fortune, and a red Fuji even more so: rare, powerful, and flawless in its symmetry. Perhaps this is why the print has enjoyed such lasting iconographic success, embodying an ideal of peace, balance, and quiet strength.

Yoshida Hiroshi, Fuji from Kawaguchi Lake, 1926.

3. Yoshida Hiroshi, Fuji from Kawaguchi Lake

If Hokusai immortalized Mount Fuji in its mythical and symbolic grandeur, Hiroshi Yoshida brought it to life in a more intimate and atmospheric dimension. His print Kawaguchi Lake, part of the Ten Views of Fuji series, offers us a contemplative, quiet, almost whispered view of Japan’s most iconic volcano. There is no threatening wave here, no fiery red sunrise—only the stillness of water, melting snow, and a landscape gently breathing.

Unlike the great masters of ukiyo-e, Yoshida wasn’t bound solely to tradition. His training included Western oil painting and watercolor, Tokyo art academies, and American museums: in fact, his first international success came with an exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1899, just as Japan was stepping into the century of industrialization. What makes him unique is his ability to blend Western perspective and chiaroscuro with the narrative subtlety of Japanese art.

In this image, Mount Fuji is seen from Lake Kawaguchi, one of the five iconic locations offering views of the volcano. It’s winter—or perhaps early spring: snow still blankets the shorelines but is beginning to melt. The water reflects the world around it in soft ripples, catching the light of a sunset that fades from pink to orange. It’s a scene Yoshida might have witnessed on one of his many hikes: he was an avid mountaineer and walker, and knew the Japanese landscape not only as an artist, but as a traveler.

One curious anecdote: unlike many of his predecessors, Yoshida was deeply involved in every step of the printmaking process. At a time when artists often left the carving of woodblocks to specialized craftsmen, Yoshida personally oversaw each stage, frequently experimenting with different color variations of the same print to capture shifting times of day or seasonal moods. For him, light was a form of storytelling—a simple pigment change was enough to transform a landscape into an emotion.

Yokoyama Taikan, Autumn Leaves, 1931.

Yokoyama Taikan, Autumn Leaves, 1931.

In Autumn Leaves, Yokoyama Taikan turns his gaze away from the ever-present Mount Fuji and instead immerses us in a scene of pure seasonal poetry. This folding screen (byōbu), with its sweeping panorama of crimson maple leaves above a blue, rippling river, is not just a depiction of nature — it is nature idealized, spiritualized, and harmonized through a uniquely Japanese lens.

Yokoyama was one of the key figures behind the creation and evolution of Nihonga, the modern form of traditional Japanese painting that emerged in reaction to the influx of Western styles during the Meiji period. What’s fascinating is how Taikan, while deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics and technique, also drew on Western influences in subtle, innovative ways — something he cultivated through his travels to Calcutta, New York, London, and Paris. In fact, his encounter in India with Abanindranath Tagore, a pioneer of Indian modernism, sparked a rare East-to-East exchange that influenced modern painting well beyond Japan.

In Autumn Leaves, we see none of the black ink Taikan would later become famous for, but we do see his hallmark innovation: the “mōrō-tai,” or “hazy style,” developed together with Hishida Shunsō. Gone are the hard outlines of classical yamato-e. Instead, the leaves seem to float, the trees to breathe, and the river to move in a delicate mist of gradated color. It’s a technique that was at first criticized as lacking vigor — “blurred and lifeless,” said some — but has since been recognized for its atmospheric power and dreamlike quality.

There’s an anecdote that reveals Taikan’s stubborn dedication to his craft: during his travels, he would sometimes bring home soil, leaves, and even bits of local flora to grind into pigments or study for color accuracy. For him, painting nature wasn’t imitation — it was immersion. This attention to natural detail, combined with the spiritual philosophy of mono no aware (the pathos of things), gives Autumn Leaves its quiet emotional force.

Interestingly, Taikan’s nationalism — inherited from his teacher Okakura Tenshin — often led him to paint Mount Fuji as a symbol of Japanese identity. But here, he chooses a quieter subject: not the mountain of gods, but the fleeting beauty of autumn. And perhaps this is even more Japanese.

4. Yokoyama Taikan, Autumn Leaves

Fujishima Takeji, Eastern Sea, about 1928.

Fujishima Takeji, Eastern Sea, about 1928.

5. Fujishima Takeji, Eastern Sea

To conclude this journey through the images of Mount Fuji and the Japanese landscape, Sunrise over the Eastern Sea by Fujishima Takeji offers yet another interpretation of nature — no longer mythical like in Hokusai, nor contemplative like in Yoshida, but deeply European in its breath and pictorial construction. Here, sea and sky merge into a chromatic synthesis that feels almost spiritual, where the narrative element — a single sailboat — is reduced to a bare whisper, like a held breath.

Fujishima, a refined interpreter of the yōga (Western-style painting), was one of the Japanese artists most capable of bridging East and West. His training in Paris, under Fernand Cormon and Carolus-Duran, along with time spent in Rome, profoundly shaped his approach to painting: light, volume, simplicity, rigor. He often told his students that the secret of painting could be found in one French word: simplicité. For him, to paint meant to strip away, to remove everything non-essential.

This philosophy is perfectly embodied in Sunrise over the Eastern Sea, where the scene is built with only four bands of color: the sea, the clouds, the sky, and more clouds — an abstraction bordering on the informal. If we removed the tiny boat on the left, the painting could almost pass as abstract. And yet, this landscape says a great deal: not about a specific place, but about the human condition, about the silent rise of time.

There’s a fascinating anecdote behind this work: in 1928, on the occasion of Emperor Shōwa’s enthronement, Fujishima was commissioned to create a painting for the imperial study. He chose the theme of dawn, as a metaphor for new beginnings. For the next decade, he chased the rising sun across Japan and its territories — from Mount Zao in the north to Yu Shan in Taiwan, from the sea to the deserts of Mongolia. Sunrise became his favorite subject in his later years, as if he were searching in the eternal rhythm of dawn for the ultimate answer to what painting truly is.

In this sense, Sunrise over the Eastern Sea is closer to Turner or Monet than to Hiroshige. It is an artwork born of European tradition, yet filtered through the eyes of a Japanese artist who deeply internalized the West without ever forgetting his own roots. A sunset? A sunrise? It doesn’t really matter. What matters is the harmony, the rhythm, the silence that speaks.

FAQ

1. What makes Japanese art unique?

Its fusion of spirituality, nature, and minimalism — combined with deep cultural continuity and openness to outside influence — gives it a distinct voice in global art.

2. Why is Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa so famous?

Beyond its striking design, it bridges Eastern and Western techniques, symbolizing Japan’s anxiety and beauty in the face of nature and modernization. It also had major influence on Impressionist and modern Western artists.

3. What is Nihonga and how is it different from yōga?

Nihonga refers to Japanese-style painting using traditional materials and methods, while yōga adopts Western techniques like oil painting and linear perspective.

4. Is Japanese art only traditional or also contemporary?

It is both. Japan excels at preserving ancient techniques (like bonsai, raku, and woodblock printing) while also being at the cutting edge of global contemporary art with figures like Yayoi Kusama and Takashi Murakami.

5. What role does Mount Fuji play in Japanese art?

It’s a national symbol, spiritual icon, and artistic muse — appearing in countless works from the Edo period to modern and contemporary reinterpretations. It reflects both stability and change in Japanese identity.

6. How did Japanese art influence the West?

Ukiyo-e prints inspired key Western movements like Impressionism and Art Nouveau. Artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, and Debussy drew directly from Japanese aesthetics.

Begin with Hokusai’s Great Wave and Red Fuji, then explore Yoshida Hiroshi’s serene prints, Taikan’s atmospheric Nihonga paintings, and Fujishima’s East-West fusion. Contemporary artists like Kusama and Shiota offer powerful modern perspectives.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli