BLACK 21X (2020) Painting by Rosi Roys.

BLACK 21X (2020) Painting by Rosi Roys.

Brief introduction to the concept of tags and graffiti

Graffitism, a social and cultural manifestation of wall painting, which takes shape in tags, graffiti, murals, stencils, etc., is distinguished by the dissemination of the stylistic features of its art exclusively on the urban fabric, a place where such creative externals are predominantly regarded as uncivilized acts of vandalism. Those who practice this "dangerous" art, who go by the name of writers and graffiti artists, dabble, among other things, in the aforementioned tagging, that is, in that first modern form of graffiti, which, born in New York in the 1960s, represents the signature by which the creator externalizes his pseudonym, aimed at finding space both in walls and alongside more complex mural works created by the writer himself. The main purpose of this procedure is to spread the name of the graffiti artist, making it known through thin and fast lines that, in addition to favoring legibility and fluidity, also take into account the speed of execution, in order to make it possible to carry out an act that is in itself illegal. Often there is a tendency to confuse tags with graffiti, when in fact with the former term we indicate exclusively the above-explained older form of graffiti, while through the latter appellation this phenomenon is made concrete by means of more elaborate and larger writings, which are enriched by particular calligraphic styles and colors, with the purpose of decorating entire walls, subway cars, abandoned places, etc.

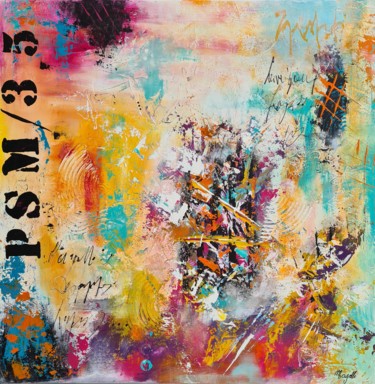

"TOILE DE PIAF" #33 (2021) Painting" by Paf Le Piaf

"TOILE DE PIAF" #33 (2021) Painting" by Paf Le Piaf

What is the difference between Graffiti and Street art?

Why until now have we talked about graffiti and not Street art? We often, and quite incorrectly, use these terms indistinctly, probably because both artistic externals come from the same context: the street! Speaking of graffiti art, this art form, which has been present on earth since prehistoric eras, became official in its being only during the 1970s, a period when it took the form of a language of protest against abuses of power, governments or the law in general, pursues the intent of manifesting the thoughts of its exponents in a personal and transgressive manner: by illegally daubing public places. Street art, on the other hand, deals with themes that are more appealing to the masses and arises mainly in urban redevelopment contexts where artists, who are no longer writers, make arrangements with the municipality to operate. In addition, other substantial differences between writers and street artists arise in training and artistic techniques; in fact, if the former are born on the street, the latter are perfected in the safe environments of studios, places where they create more elaborate subjects, the creation of which involves too much time for those who have to be chased by the police.

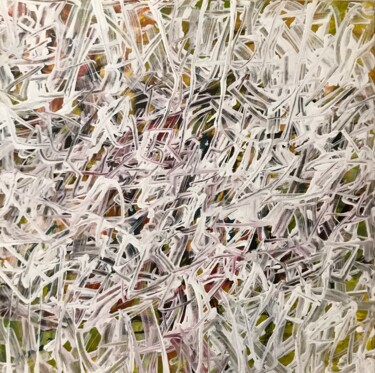

"GRAFFITITAG" GRAFFITI CANVAS BY MONKER (2023)Painting by Monker.

"GRAFFITITAG" GRAFFITI CANVAS BY MONKER (2023)Painting by Monker.

When Street art meets Abstraction: some case studies

As partly anticipated above, we are accustomed to seeing the graffities and tags on the walls, mostly monochrome, of streets, abandoned buildings, factories and much more, or, in the case where we talk about Street art, similar stylistic features are manifested within the spaces of museum institutions, art galleries, cultural venues, more or less authorized walls, collectors' homes, etc. Indelibly linked to this view is the popular belief, that the subjects and techniques of urban art turn out to be exempt, apart from when it comes to some allusions to the closest Pop art, from the more general narrative of art history, within which to me appear, sometimes conspicuously, some peculiarities that the aforementioned art movement inherited from abstraction, especially when it tends and evokes geometric forms, artistic techniques, spatial dimensions, textures and allusions to a reality evidently untethered from the images of everyday life. When said will be demonstrated through the analysis of some case studies, which, in a more or less imaginative way, will associate the abstract narrative with the "urban" one, referring to the work of some Artmajeur artists, such as: Monker, Kesa Graffiti, Vincent Bardou, Saname, and Pierre Lamblin.

SUN 2023 (2023)Painting by Kesa Graffiti.

SUN 2023 (2023)Painting by Kesa Graffiti.

GRAFFITI BURNS (2022) Painting by Vincent Bardou.

GRAFFITI BURNS (2022) Painting by Vincent Bardou.

Regarding the first example, I want to begin by presenting Piet Mondrian's Composition No. 1: Lozenge with Four Lines (1930), a painting whose antecedents date back to 1918, when the master created diamond-shaped works in order to give a more dynamic rhythm to his abstractions, which were created by the unconventional orientation of square canvases, which were turned on a forty-five-degree angle with an angle at the top. Added to this innovation is that of the introduction of the diagonal line of the edge of the canvas in his grid of horizontal and vertical lines, which appear to extend beyond the boundaries of the support to intersect with the diagonals at varying intervals. The concepts that are made explicit by this abstract investigation of space and geometry reside in a careful search for an ideal balance, aimed at foreshadowing the minimalist interest of pure form, as well as the preference for the use of muted colors. In the contemporary context of street art, a similar change in the orientation of geometric forms, in this case concerning that of the rectangle, occurs in Monker's painting Graffititag, a work in which the grid is replaced by a superimposition of geometric figures on which white and gray tags stand out, placed on a background inclusive of similar colors to be added even to darker shades, reaching as far as black. About the aforementioned Kesa Graffiti, on the other hand, I introduce to its work by talking about Wassily Kandinsky's Circles in a Circle (1923), the Russian master's first masterpiece to investigate primarily the figure of the circle, which, in its most extensive depiction in black, encourages the viewer to focus on the multiple round figures within it, a place where we also find diagonal stripes intrinsic to it. Similarly, Kesa's realized circle Graffiti in Sun is aimed at highlighting its content, in which graffiti, made in black and white, stands out against a red background, where the abstract dripping technique is distinguished by the presence of yellow, white, black, orange and red splashes. Continuing with the narrative, a further case study is offered to us by the work of Vincent Bardou, who, in many of his works, just as is also the case in Graffiti burns, offered the viewer the possibility of knowing what lies beneath the first layer of paint, as in the latter work the arrangement on the support of acrylics and spray paint is "surrealistically torn apart," to provide us with the vision of an underlying dimension of the canvas, aimed at leading us at an inexorable reflection on space, a theme extremely dear to the previous spatialist thought. Precisely the latter movement, born in 1946 and founded by Lucio Fontana in twinning with the Galleria del Cavallino in Venice, innovatively set aside the pictorial image in order to address, through artistic work, the problem of the all-encompassing perception of space, to be understood as the sum of the categories of time, direction, sound and light. In order to better understand what has just been externalized, it is worth explicating how it was Fontana himself, through his cuts, who revolutionized art by introducing the physical three-dimensionality of painting, to be understood as the realization of the urgency to overcome the most stagnant artistic conventionality, in order to insert the most innovative dimensions of time and space.

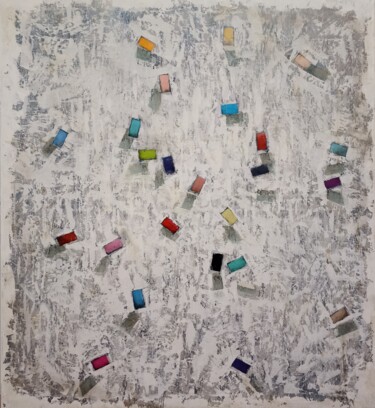

TRACE N2206 (2022)Painting by Saname.

TRACE N2206 (2022)Painting by Saname.

LOVE TAG (2022) Painting by Pierre Lamblin.

LOVE TAG (2022) Painting by Pierre Lamblin.

After Bardou, it is the turn of Saname, a French artist whom I want to juxtapose with the example of Jackson Pollock's Number One (Lavender Mist, 1950), a painting, which, made in an old barn in the East End of Long Island, transformed by the master into a studio, perfectly embodies that artistic breakthrough achieved by Pollock between 1947 and 1950, concretized through the maturation of his earlier experiments on dripping and splattering color on ceramic, glass and canvas on an easel. In the particular case of the above-mentioned masterpiece, the artist spread the large canvas on the floor of the barn and then dripped, poured and threw pigments from paint-soaked brushes and sticks as he walked around the support. This ritual act is repeated, probably through a similar creative process, in the making of the background of Trace n2206, intended to accommodate a "minimalist" graffiti, which takes shape on a canvas prepared with the aforementioned dripping technique. Finally, the analysis of the last case study stems from the observation of certain peculiarities found in multiple masterpieces by Mark Rothko, including, for example, Number 10, (1950), Red, Brown, and Black, (1958) and Orange, Red, Yellow, (1961). Precisely in these paintings all the rectangular shapes, which allow the creation of a kind of frame, are arranged avoiding extending to the edges of the canvas, hovering just above the surface. This floating sensation is augmented by the afterimage effect, according to which each color segment affects the perception of adjacent ones. In a similar way to what has just been described, the kind of "passe-partout" of Love tag becomes apparent, which, made in blue, black, pink and yellow and arranged between the tags and the frame of the work, accommodates within it romantic dripping inscriptions, made si black background in the same or similar chromatics.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli