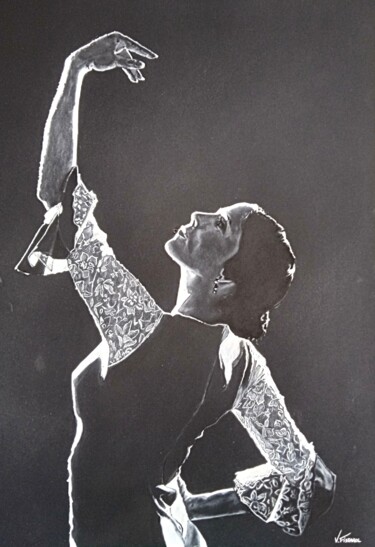

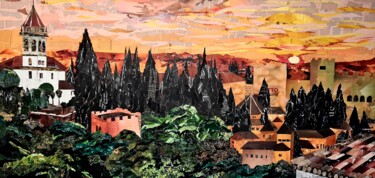

DOLORÈS (2018) Painting by Val Escoubet.

DOLORÈS (2018) Painting by Val Escoubet.

A dancing climax of passion

This narrative tells, through the evocative images of some well-known masterpieces of art, a figurative story built on a climax of passion, that is, having the purpose of revealing, through the discipline of dance, a growing instinctive and ardent impulse, aimed at animating the dancers in their more or less unreflective performances. As when climbing a mountain, in search of the sensations one feels on the summit, I start walking uphill to arrive, step by step, on the focal point of the narrative, crossing the foot, the slope and the sub-top of the mountain range, terrains that I wanted to imagine, in their progressive explosion of passion, in the features of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Six Dancers (1911), in those of Henry Matisse's The Dance (1909-10) and in Picasso's The Three Dancers (1925. Speaking of the foot of the mountain, Kirchner's masterpiece immortalizes, as per the title, six frontally aligned dancers, intent on assuming mechanical, angular poses that make them perceive themselves as a kind of mechanical dolls, while wearing a pink tutu and presenting their hair wrapped and gathered toward the nape of the neck. The girls, who perform on a stage visible behind them, assume coordinated poses, hinting to us that they are most likely expressing themselves through the rigorous and studied languages of ballet, which is less prone to mainly instinct-driven outbursts and wilder inspiration.

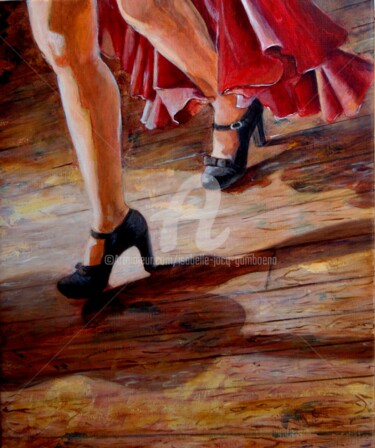

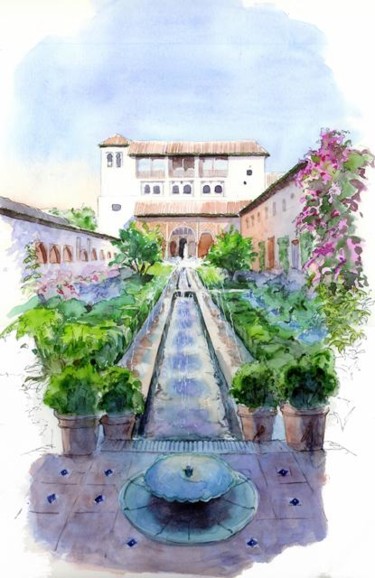

DANCE FULL OF PASSION (2023) Painting by Marta Zawadzka.

DANCE FULL OF PASSION (2023) Painting by Marta Zawadzka.

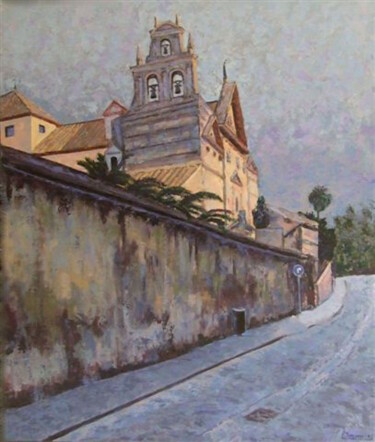

As I continue walking, I take the opportunity to take a good look around, to fully enjoy the beauty of the landscape, noting the gradual increase in the slope's gradient, which brings me to a more wild terrain, within which the "inhibitory brakes" of academic dance are progressively, and gently, replaced with the freer languages of modern dance, exemplified first by Matisse's The Dance and, in the sub-peak section, by the more wild dance of Picasso's The Three Dancers. Speaking of the first masterpiece, within a horizontal composition, aimed at assisting the movement of dance, a group of dancers are distributed who, in their formation, reach up to the rectangular edges of the support, expressing their free nudity by means of a rotating pattern, in which the bodies assume unbalanced and twisted positions. From a symbolic point of view, the bodies, stripped of their clothes, indicate a return to a nature devoid of complex conjectures, where spontaneity, joy of life and the purest expression of being are powerfully imprinted. In spite of this, the rotating movement confers order and precision, "depriving" the characters of total freedom of expression, who, though caught up in their dance, must stick to a certain trajectory, an aspect that, instead, is lost in the overlapping and intricate forms that animate the passionate dance captured by the aforementioned Picasso painting. Referring back to the description of The Three Dancers at the Tate Modern (London), the Spanish master's work represents our sub-top in that it presents a remarkable "emphasis on violence and sex," spontaneous and passionate emotions skillfully rendered by the imposing presence of the three angular and distorted figures in harsh colors, having the purpose of depicting a group of dancers during their rehearsals. Now, just like a child who in the journey nags his parents to know how far it is to the desired destination, I pose this question: when do we reach the top of the narrative? The high point is revealed to us by a small, but important, change in context, for if Picasso's rehearsals are by definition tied to a set plan, and thus slightly less impetuous, the improvisation, or going onstage, represents the pinnacle of our narrative, aimed at leaning out to see the view from the top of the passion of flamenco, a form of dance and music of Andalusian origin (Spain), which arose in the late eighteenth century not as a form of spectacle, but as a need to vent joys and sorrows in an intimate, private and, consequently, free, ardent and spontaneous language. Such a summit is represented, speaking of painting, by the likes of Joaquín Sorolla's The Flamenco Dancer (1914) and Julio Romero de Torres' Happines (1917). With regard to the former, it presents a sharp contrast between the dancing figure in the foreground and the window in the background, a feature that gives the work a strong sense of three-dimensionality, designed to fully capture the fleeting moment of the performance, which is translated through similarly broad, unrestrained and vivid brushstrokes, aimed at capturing even the movement of the tassels of the shawl, as well as all the sensuality of the dancing body. As far as Happines is concerned, however, Torres' painting seems, by its very compositional secrecy and the attire of the effigies, to be a courtiers' party rather than a flamenco performance, although, leaving aside the two mocking figures in the background and the Greek pose of the reclining woman, the viewer's attention falls mainly on the central female figure, intent, with great seriousness, on interpreting, mainly with her arms, the mysterious melody played by an extremely involved guitarist, who, without exchanging looks with the viewer, seems caught in amorous intercourse. Finally, the passionality of flamenco, the snowy but "caliente" summit of this tale, is echoed in some of the works of Artmajeur's artists, who offer us opportunities to delve deeper about this well-known form of music and dance.

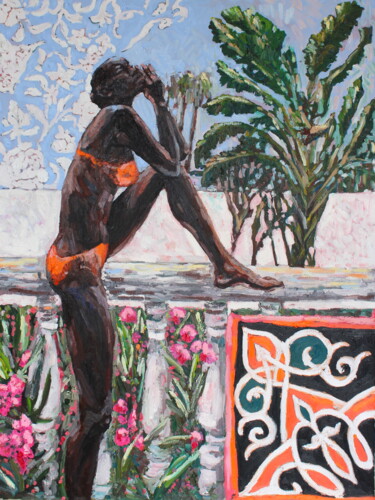

FLAMENCO (2021) Sculpture by Karen Axikyan.

FLAMENCO (2021) Sculpture by Karen Axikyan.

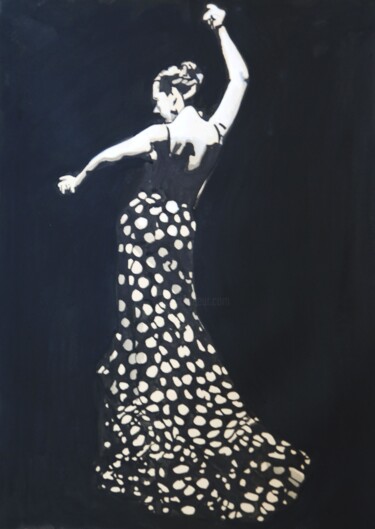

FLAMENCO (2021) Painting by Hugues Rubio.

FLAMENCO (2021) Painting by Hugues Rubio.

Hugues Rubio: Flamenco

At the two ends of the canvas, as if at a kind of opposite poles, we find the sinuous rotation of the hands of the flamenco dancer portrayed by Rubio, who, dressed in black against an indistinct dark background, turns her concentrated and passionate gaze toward the viewer, probably to invite him to take part in her dancing seductive game. If the viewer's intention is to seize this opportunity, he, by taking part in the dance, will also surely come to know the context in which the said action takes place, a place that will probably be similar to the shadow-rich interior in which a well-known dancer in the history of art is placed, namely, the gypsy woman who is the protagonist of El Jaleo (1882), a canvas by John Singer Sargent that depicts her as she is positioned to suggest a forward movement, marked precisely by the peculiar movement of her outstretched left arm, to be understood as an accurate representation of the standard technique and style of flamenco dance. All this takes shape in a shadow-rich context, which, lacking a barrier between the spectator and the dancer, helps to create the illusion of being present at the actual event, which is extremely charged with the energetic rhythms of dance and sound. Finally, it is important to emphasize how the spontaneity of the aforementioned performance is drastically opposed to the way the masterpiece was created, which the American master planned in his composition for at least a year, anticipating it with a series of preliminary studies, aimed mainly at studying the posture of the protagonist.

FUEGO FLAMENCO (2022) Digital Arts by L.Roche.

FUEGO FLAMENCO (2022) Digital Arts by L.Roche.

L.Roche: Fire flamenco

Roche's sensual digital artwork fuels the passion inherent in the flamenco dance itself by adding the component of nudity, as it appears that the dancer's dress leaves her breasts uncovered, parts of her body, which, cleverly turned to the left side of the support, accompany the direction of the protagonist's captivating shifty gaze. Thinking instead of the technique with which the dancer has been depicted, I feel compelled to contrast the extreme topicality of digital art with the ancient subject that it wished to immortalize, since flamenco is a Spanish musical genre that developed in Andalusia, especially in the areas of Cadiz and its ports, around the 18th century, a time when, probably, the fusion between Andalusian popular culture and that of the gypsies took place. This encounter gave birth to flamenco singing, a melody that was usually accompanied by guitar music and a stick that was beaten on the floor, as well as by a dancer performing a series of choreographed dance steps and improvised styles. We can now imagine the protagonist of Fire flamenco, who, according to the oldest tradition, moves to the rhythm of a song intended to tell the legends and stories of daily life, reflecting the experiences of a marginalized subculture existing within a remote, predominantly white to Christian Spain.

FLAMENCO (2020) Sculpture by Martinez.

FLAMENCO (2020) Sculpture by Martinez.

Martinez: Flamenco

The metal forged by Martinez gave birth to a flamenco dancer, whose features make us think of a modern stylized version of Dalinian dancer (c. 1949), a work that Salvador Dali conceived to make eternal the intense and passionate rhythms of Spanish flamenco, a dance he was deeply fascinated with, perhaps in part because it was emblematic of his homeland, as well as known for its ability to explore the full range of human emotions. In addition, I take this opportunity to report a curious anecdote, involving the aforementioned dance and music form and the Spanish master, in that the latter tried his hand at flamenco action painting, first improvising a live painting while accompanied by the quintessential Andalusian music in the background. Don't believe it? You are dead wrong! In fact, there is even a video, viewable on YouTube, in which the artist paints a horse and rider to the notes played by guitarist Manitas de Plata and sung by Jose Reyes, both fathers of the artists who started the group "The Gypsy Kings." In addition, Salvador often hung out with the flamenco dancer "La Chinga," who, originally from Catalonia like the master, always danced barefoot, so much so that Dali once had her perform on a blank canvas, on which, leaving the traces of black paint that colored her feet, he gave life to a live paint-dance, which took place in the countryside of Port Lligat (Girona, Spain).

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli