Let us know if you would like to see more photos of this artwork!

- Back of the work / Side of the work

- Details / Signature / Artwork's surface or texture

- Artwork in situation, Other...

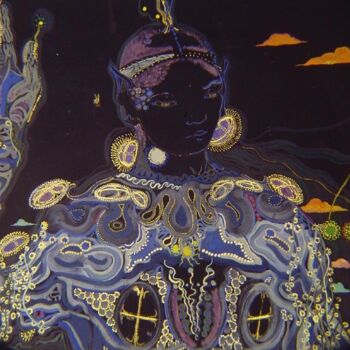

The evening, a river, a hill and The 4 invisible Kabuki players. here the kabuki players have instea (2010) Painting by Rob Arbouw

Sold by Rob Arbouw

-

Original Artwork

Painting,

- Dimensions Height 19.7in, Width 25.6in

- Categories Paintings under $1,000

The name Edo derives from the regimes capital city Edo that is now Tokyo. Kabuki was a wild, new form of entertainment in the ukiyo, or Yoshiwara, the registered red-light district in Edo. Kabuki was an extravagant social setting. A diverse crowd gathered under one roof, something that happened nowhere else in the city. The variety of the social classes which mixed at the kabuki performances was what irked the shogunate. Kabuki theaters were a place to see and be seen. Kabuki featured the latest fashion trends and current events. The stage provided good entertainment with exciting new music, patterns, clothing, and famous actors. The theatre was an all-day event; the performance went from morning until sunset. The teahouses surrounding or connected to the theater provided meals, refreshments, and good company.

The area around the theatres was lush with shops selling kabuki souvenirs. Kabuki started Japanese pop culture and maintained a devise for social inclination.

Not long after the original performance, word traveled fast, and kabuki became tremendously popular. The shogunate was never partial to kabuki theatre and all the mischief it brought. Kabuki went through tremendous leaps, trying to appease the harsh restrictions by the government. Women’s kabuki, called onna-kabuki, was banned from the stage in 1629 for being too erotic. Following onna-kabuki, young boys performed in wakashu-kabuki, but since they too were eligible for prostitution the shogun government soon banned wakashu-kabuki as well. Kabuki finally settled with adult male actors, called yaro-kabuki in the mid 1600’s.[9] Male actors played both female and male characters. The theatre was as popular as ever, and remained the entity of the urban lifestyle even until modern times. Although kabuki was performed all over ukiyo and other portions for the country, three kabuki theatres set themselves apart from the rest and became the top theatres in ukiyo. The Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za theatres are where some of the most successful kabuki performances were and still are held.

Fires started terrorizing Edo in the 1840s during dry spells. Kabuki theatres, traditionally made of wood, would constantly burn down and be forced to relocate with in the ukiyo. The area that housed the Nakamura-za was completely destroyed in 1841. The shogun refused to allow the theatre to rebuild saying it was against fire code.

This sort of censorship happened was forced onto all of the theatre houses, making abiding by the shogun laws extremely difficult. This added to the underground life and mobility of the actors in Edo, since the government tremendously regulated them. The shogunate did not welcome town merchants mixing and trading with actors, artists, and prostitutes. The shogunate took full advantage of the fire crisis and in 1842, forced the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za, the three main kabuki theatres out of the city limits and into Asakusa (a northern suburb of Edo). The shogun also relocated the puppet theatre alongside kabuki. This exile was desired almost from the start of kabuki. Along with the theatres, all other theatrical attributes were forced out as well, including the actors, stagehands, and all others associated with the performances. The areas and life styles around the theaters migrated as well, but due to the inconvenience of the new location, attendance was low.

The new location for the theatre was called Saruwaka-chō, or Saruwaka-machi. The last thirty years of the Tokugawa shogunate’s rule, when kabuki was located in the Saruwaka-machi and banned from Edo, is referred to as the Saruwaka-machi period. This period produced some of the gaudiest kabuki in Japanese history.

The Saruwaka-machi became the new theatre district for the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Kawarazaki-za theatre houses. The district was located on the main street of Asakusa, which ran through the middle of the small city. The street was renamed after Saruwaka Kanzaburo, who initiated Edo kabuki in the Nakamura Theatre in 1624. The kabuki theatre district was now located on the new Saruwaka street in the Saruwaka-machi.

Other things were happening around Edo at the time. European artists began noticing Japanese theatrical performances and artwork. Artists like Claude Monet were greatly inspired by Japanese wood block prints. The western interest prompted Japanese artists to create prints of everyday life depicting theatres, brothels, main streets and so on. One artist in particular, Utagawa Hiroshige, did a series of prints based on Saruwaka from the Saruwaka-machi period in Asakusa. Saruwaka-machi had truly become the new theatre district, and was even getting recognized as so by artists outside the world of kabuki.

The mentality of kabuki had been almost destroyed by this relocation, removing the play’s most abundant inspiration for costuming, make-up, and story line, but kabuki still worked with what it had in the Saruwaka-machi. Ichikawa Kodanji fourth was one of the most active and successful actors during the Saruwaka-machi period. Deemed unattractive, he mainly performed buyo, or dancing. He performed in dramas written by Kawatake Mokuami, who also wrote during the Meiji period to follow.

Kawatake Mokuami commonly wrote plays that depicted the common lives of the people of Edo. He used new techniques for kabuki, integrating shichigo-cho (seven-and-five syllable meter) dialogue and music such as kiyomoto. His kabuki performances became quite popular once the Saruwaka-machi period ended and theatre returned to Edo, many of his works are still performed today. The Saruwaka-machi period only lasted thirty years. In 1868, the Tokugawa shogunate fell apart. Emperor Meiji was restored to power and moved from Kyoto to the new capital of Edo, or Tokyo, thus starting the Meiji period.

Kabuki was reinstated to its birthplace in the ukiyo of Edo. Kabuki became more radical in the Meiji period. New playwrights took kabuki under siege and created new genres and twists on traditional stories. Modern styles started in the Meiji period.

Related themes

CURRICULUM VITAE

Geboren: 20 - 9 - 1953 Heerlen

Opleidingen:

2000-2001 Desk Top Publishing / html / Typographie (diploma)

Photoshop, Illustrator, QuarXpress, Flash, Fireworks, HTML, MS Office

1978 - 1979 Pedagogisch Didactische Bijscholing

1972 - 1978 Stadsacademie voor Toegepaste Kunsten;

Monumentale vormgeving, schilderen en grafiek. Maastricht (diploma)

1965 - 1972 Middelbare school (diploma)

Exposities

2007 Als man en vrouw schiep hij de mens,

Grote Laurenskerk Alkmaar

2006/07 CU in Babel, Utrecht, groepsexpositie

2005/06/07 Realisme 5,6,7. Amsterdam door Besselaar Contemporary Art

2006 Kunstrai, "Lagunes" ,Amsterdam door Kunsthandel Bas Meijer, Utrecht"

2002/2003 De Salon, Jaarbeurs, Utrecht

1999 Assistentie restauratie 'Het Schip '

Centraal Museum Utrecht

1998 ‘Zien is geloven’, St.Bavo , De Vishal, Haarlem

‘De Salon’ Centraal Museum, Utrecht

1997 ‘Under my skin’ Artis, Den bosch

Galerie De Praktijk, Amsterdam (solo)

CBK, Utrecht (solo)

1996 ‘De Salon’, Centraal Museum, Utrecht

1994 ‘Begane grond’ Utrecht

1992 Kasteel Hernen, Gelderland

‘Icon - assemblys in a bizantian context’ (solo)

1988 Installations Schuwirth & Van Noorden,Maastricht (solo)

Museum Zonnehof, Amersfoort.’ Kunst en het meisje achter de kassa’

1988-1991 Social Sculpture, Jospeh Beuys, Z.Duitsland

1987 Installations Leeuwarden

1985 galerie Inge Schrofer, Amsterdam (solo)

1984 Koninklijk Paleis op de Dam, Amsterdam

Stipendia:

1995 - 1999 Stipendia van de Nederlandse Staat

1992 Projectstipendium prov. Utrecht

1988 Projectstipendium prov. Utrecht

Werk in Partuculiere en Bedrijfs Collecties:

In Thailand, Zwitserland, Duitsland, Verenigde Staten, Engeland

Frankrijk, Spanje, Belgie en Nederland

ABN-AMRO - A'dam, ING-group - A'dam; AEX- effectenbeurs - A'dam, - Tweede Kamer, Den Haag

Representatie en stock:

Galery Negenpuntnegen, Roeselare, Belgium

Galery Besselaar, Utrecht, the Netherlands kunstenaars/werk_arbouw.htm

Galery Demedici, Nunspeet, the Netherlands

Galery Het Wed, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Binnen afzienbare tijd in Carré d’artistes - 9, allée Claude Forbin - 13100 Aix-en-Provence, Frankrijk

Oudwijkerdwarsstr 13

3581 la Utrecht

Atelier: De Ruimte

Utrechtseweg 38-40,

Zeist

tf 31 + (0)30 2518489

31 + (0)6 12065242

index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2567&Itemid=168

subsel.php?p_att_1=1&p_val_1=1007415&lgType=mg&lgAtt=1&l...

-

Nationality:

NETHERLANDS

- Date of birth : 1953

- Artistic domains:

- Groups: Contemporary Dutch Artists