Women we're going to introduce here aren't "wives of", they were already artists before they met their husbands, had their own styles and ambitions, and were as skilful and talented as their companions.

Elin Danielson-Gambogi, After Breakfast , 1890.

Elin Danielson-Gambogi, After Breakfast , 1890.

1. Jo Hopper (and Edward Hopper)

Everyone knows Edward Hopper, but who remembers his wife, Jo?

Her real name was Josephine Verstille Nivison, and she was destined for a very promising future. Born in Manhattan in 1883, she oriented herself towards an artistic career at an early age, expressing herself easily through drawing and acting while in college. In 1905, when she was just 22 years old, she met Robert Henri, a major figure in American realism. After asking her to pose for one of his portraits (The Art Student, 1906), he became her drawing teacher and formed a relationship with her that was as friendly as professional.

She then worked as a teacher for young girls and devoted her free time to oil painting. Until she was 40, she enjoyed a completely independent life, socializing with many artists, traveling through Europe with her art teacher and fellow aspiring painters, and attending art camps in New England each summer. She began to gain notoriety for exhibiting some of her artwork in New York galleries, alongside such renowned artists as Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Man Ray. It was in this artistic microcosm that she met her future husband Edward, first at art school and then during various artistic colonies in the US.

Robert Henri, The Art Student (Portrait of Josephine Nivison), 1906.

Robert Henri, The Art Student (Portrait of Josephine Nivison), 1906.

The two lovers got married in 1924. Josephine V. Nivison became Jo Hopper and participated in the construction of a couple as tumultuous as inspiring. They traveled across America and painted together, but the fantasy of the creative idyll quickly turned into a marital burden for Josephine. The pair quarreled regularly, and these recurring tensions weakened her ambition. Gradually, she neglected her passion to become her husband's impresario, and took over most of the domestic tasks to give him as much time as possible to create.

Her husband quickly became a legend, during his lifetime, thanks to enigmatic, refined and silent artwork, depicting the daily life of a deeply lonely America. However, without the assistance of his wife, Edward Hopper could never have achieved the success we recognize today. More than just a model or an ordinary muse, Josephine contributed enormously to her husband's artistic rise. Because he was shy and reserved, she helped him make connections with professionals in the art market, in order to enhance his artwork.

If you are already saddened by Josephine's renunciation, hang on, because there is much, much more heartbreaking in this story:

Edward Hopper died in 1967, at the age of 84, with no descendants. His widow, Josephine, survived him for a year, before she too died at the age of 84, in 1968, in general indifference. She took advantage of these few months of mourning to organize the posterity of her and her husband's artwork. She documented their work and bequeathed a considerable number of the couple's artworks to the Whitney Museum in New York. Today, all of Edward's signed artworks are on display, but there is no trace of the hundreds of artworks created and bequeathed by Josephine.

Jo Hopper, Untitled (Study of landscape around the Hopper House with Cape Cod Bay in distance).

Jo Hopper, Untitled (Study of landscape around the Hopper House with Cape Cod Bay in distance).

Are these artworks stored in the museum's storerooms? If only...

In fact, the vast majority of Josephine's artwork is now completely gone. Since her death, the Whitney Museum has never exhibited a single artwork by the artist, and worse, it has made sure to get rid of this phantom stock, justifying itself with a lack of space in the museum's reserves. The museum burned some of the artwork, and gave the rest to hospitals, which, for lack of space, also destroyed most of it.

Of the hundred or so artworks produced, only a few engravings, watercolors and black and white photographs remain today.

A sinister reward for a woman who sacrificed her destiny in order to establish her husband's triumph.

2. Margaret Keane (and Walter Keane)

Margaret Keane, In The Garden, 1963.

Margaret Keane, In The Garden, 1963.

Do you recognize those large eyes?

Some of you probably know this story, as it was the subject of a sublime movie directed by Tim Burton in 2014: Big Eyes. (already mentioned in our article When cinema pays tribute to the masterpieces of Art History). It's the most mind-boggling impersonation since the advent of modern art: an emancipatory epic mixing machismo, malice and indecency. Hang on, we're taking you into the gloomy and luminous world of Margaret Keane.

This curious artist was born under the pretty name of Peggy Doris Hawkins, in 1927, in Nashville (Tennessee). When she was only 2 years old, she was victim of an accident during a seemingly benign medical operation, which irreparably damaged her right eardrum. From an early age, she expressed a deep interest in drawing, an activity she practiced extensively. At the age of 10, she registered in a drawing school to deepen her knowledge and technique. At this time, she already produced her first oil paintings. Her injured eardrum prevented her from hearing properly. This handicap will lock her in a particular solitude and will oblige her to concentrate on the glance of her interlocutors to better understand them (you see the link with the famous big eyes). Shy and reserved, she progressively isolates herself in a bubble of solitude, which is felt in the choice of her subjects (children, women, cats, dogs, horses), as well as in the choice of colors and the technique used (oil paint mixed with acrylic).

Her unusual style is on the border of kitsch surrealism and naive art.

Discreet, unknown and distant from the art world, it was when she was 25 years old, in the mid-1950s, that her destiny was radically changed. She met an artist with a mediocre technique but an emerging success: Walter Keane. Although they were both married, they fell under each other's spell and were united in 1955 in Honolulu.

Bob Campbell, Margaret Keane and Walter Keane, The Chronicle.

Bob Campbell, Margaret Keane and Walter Keane, The Chronicle.

Walter Keane is an atypical character: he's charismatic, seductive, smooth-talking, and undoubtedly egocentric. A fine example of toxic masculinity. He quickly falls in admiration of his beloved's wide-eyed paintings and becomes secretly jealous of her mastery of the brush. He knows that her paintings are unique and can be sold at a good price. With his charisma and commercial experience, he decides to do what Margaret, too shy, was not able to do: promote and sell her work.

A husband who helps his wife, a reserved artist, to sell her artwork: what's the harm?

To attract buyers, Walter exhibits his wife's artwork in a San Francisco club. Faced with the success of this operation and numerous admirers who want to know more about the signature accompanying these strange portraits, her husband decides, without his wife's knowledge, to pretend to be the author of the artworks. It was the beginning of a vast trickery that lasted several years and caused Margaret enormous suffering. Too fragile to defend herself against the impostures and threats of her husband, she will remain silent and will even go so far as to confirm in public that he is really the author of these magnificent faces with doe eyes.

Little by little, Walter Keane locks himself into his illusion of success. Since he's a very good salesman, artworks are sold out faster and faster, and money is flowing in. So he begins to invent a mythology around "his" work, and locks Margaret into his own lies, channeling her emancipatory ardor with threats and intimidation, and forcing her to paint all day (sometimes even up to 16 hours a day). On the other hand, big American galleries were snatching up her paintings, and even Andy Warhol fell under the spell.

Bill Ray, Margaret et Walter Keane, Life Magazine, 1965.

Bill Ray, Margaret et Walter Keane, Life Magazine, 1965.

Fortunately, one day, the pressure becomes unbearable for Margaret. She decided to leave Walter, and in 1970, she announced live on the radio that she was the true creator of these paintings with big eyes. After a long period of polemics and judicial crusade, Margaret is finally recognized for her talent, and the sad and melancholic look of the children she painted when she was a victim of her husband's cruelty gives way to tender, blooming and colorful portraits, symbols of a newfound joy of living. A well-deserved happy ending, contrary to Josephine Hopper's desolate posterity.

And if you have never seen Big Eyes, Tim Burton's film about the tumultuous life of Margaret Keane, we highly recommend it!

3. Sophie Taeuber-Arp (and Jean Arp)

Although unknown to the public, the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp enjoyed a career that was as dazzling as exceptional. At ease in many disciplines: painting, sculpture, sewing, architecture, applied arts and dance, she frequented the greatest artists of the early 20th century, and was an emblematic figure of the Dada movement, constructivism and concrete art.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Dada Head, 1920. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Dada Head, 1920. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

However, nothing predestined the young Sophie Taeuber for a great artistic career. She was born in 1889 in Davos, Switzerland. Her father, a pharmacist, died when she was only 2 years old. She grew up with her mother, a draughtswoman and photographer, and her siblings in the deep, pastoral Swiss countryside with weavers who taught her the art of sewing. Her mother encouraged her to develop her early artistic gifts, and even served as a model. When her mother died at the age of 20, Sophie decided to take her destiny into her own hands and went to study applied arts in Munich and Hamburg, Germany. There she discovered (among other things) ceramic art, wood turning, design and costume making.

In 1915, while the World War I was raging, she was forced to return to Switzerland. She settled in Zurich and made many artist friends, themselves forced refugees, fleeing the ravages of a conflict they didn't support. There, she affirmed her artistic talents and met Jean Arp, whom she married in 1922. Even if all isn't so sweet in the Taueber-Arp couple, we' re far from the tensions between Edward and Jo Hopper, or the manipulations exercised by Walter Keane on his partner. The duo survives on Sophie's income, but creates together, and inspires each other.

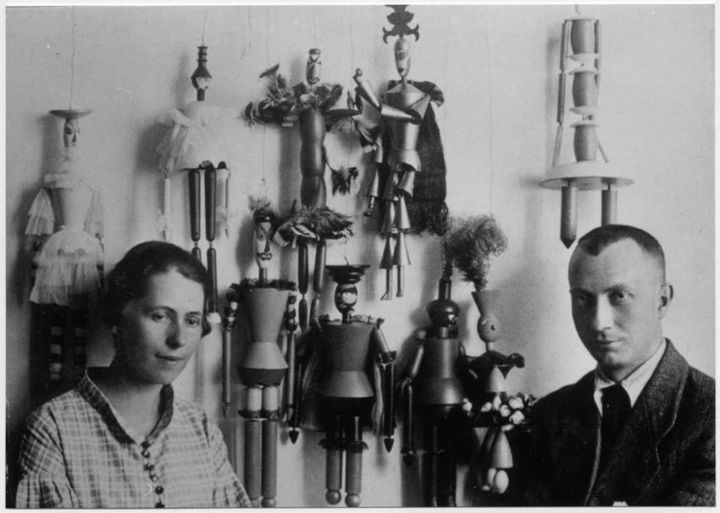

Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp, Ascona (Spain), 1925.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp, Ascona (Spain), 1925.

In 1929, Sophie and Jean obtained French nationality. They took advantage of this new beginning to settle in Meudon, near Paris. Jean was already well known on the Parisian scene and introduced Sophie to many of the influential artists of the time who would become her friends, including Max Ernst or Sonia and Robert Delaunay. The guests crowded the door of their home-studio in Meudon, and Sophie's ambitions began to be curtailed by her husband's success. At this time, she was seen more as the hostess and wife of Jean Arp, who was always the center of attention. She produced a lot of artworks during this period, but dared less and less to present them, preferring the comfort of withdrawal to the arrogance of the spotlight that she perceived in her husband's eyes.

The union between Sophie and Jean was a far cry from the toxic tensions that bound the Hopper and Keane couples together. When Sophie died of carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty wood stove in 1943, her husband was inconsolable. It would take years for him to return to a normal life, and his entire artistic output was influenced by his grief over his love. He also demanded that his own artwork could only be exhibited alongside Sophie's. A virtuous request with paradoxical consequences, since the name of Sophie Taeuber, wife but independent artist, will forever be associated with the name of Jean Arp.

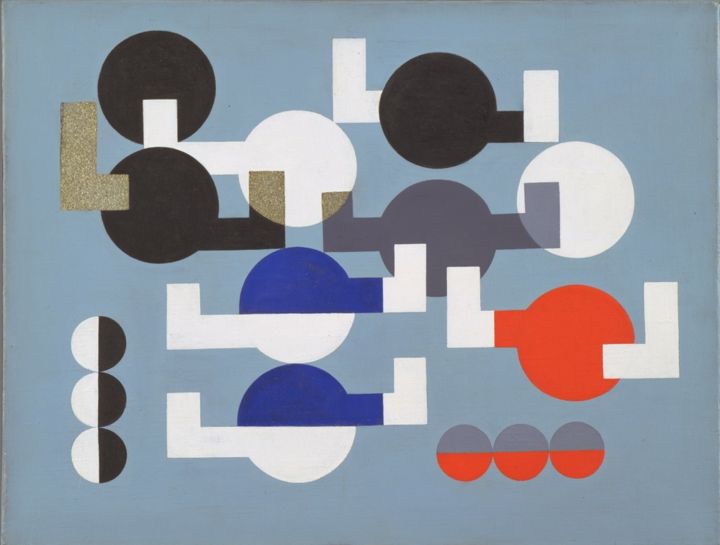

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition of Circles and Overlapping Angles, 1930.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition of Circles and Overlapping Angles, 1930.

Despite all these efforts, Sophie was quickly forgotten by the public, which was only interested in Jean Arp's artworks. The fault of a system: institutions, museums, galleries, and collectors not wishing to recognize the importance of such a powerful work, because produced by a woman. Recently rediscovered at the end of the 20th century, her Dada face is now featured on 50 Swiss franc banknotes, and international institutions are snapping up her radical, unique, and original artworks.

4. Lee Krasner (and Jackson Pollock)

Lee Krasner, Combat, 1965. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Lee Krasner, Combat, 1965. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Lee Krasner is now considered a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism in the US, although she was for a long time overshadowed by the still-vigorous aura of her husband, Jackson Pollock, who caused a stir in the auction rooms with every appearance of one of his legendary drippings.

Born in the United States in 1908 into a family of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants who had fled anti-Semitism and war, she showed a strong interest in artistic practice at a young age. Like her colleagues Jo Hopper, Sophie Taeuber and Margaret Keane, she wanted to pursue an artistic career from an early age, so she joined a school for girls in Washington, D.C., which had an art curriculum. She quickly graduated as an art teacher, and gradually built a network of artist and art professional friends who stimulated her creativity and ambition.

In 1933, she joined the American Abstract Artists movement, and met the creative elite of the time: Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman or Clyfford Still, to name a few. She creates abstract, gestural, and expressive artwork on large formats, and experiments with a multitude of techniques: painting, charcoal, collage, mosaic... Very exigent on her own work, she regularly destroys her canvases, and sometimes recovers pieces of them to add to new creations. As a result, the number of surviving artworks is very small: her catalogue raisonné lists about 600 known artworks, which is quite limited for an artist who produced for nearly 50 years.

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in their studio, 1950. Lawrence Larkin

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in their studio, 1950. Lawrence Larkin

She met Jackson Pollock in 1941. They fell in love and got married 4 years later, in 1945. From a creative point of view, the two were mutually inspiring, venturing into similar areas without being vulgar copy and paste. Lee brings her expertise and knowledge and does everything she can to enhance her husband's artwork. Their approaches are different, but their ambitions are the same. Through his wife, Jackson Pollock met influential critics and gallery owners such as Peggy Guggenheim and Clement Greenberg. Their relationship was a true exchange: Lee advised Jackson to stop giving titles to his works so that the public could contemplate his paintings without looking for external references, while Jackson helped his wife to take more risks in the realization of her artworks.

However, even if things are going well in the studio, outside, feelings are very different. Lee Krasner regularly suffers from the public reception of his identity. Contemplators would systematically make the link between her artwork and that of her husband. Critics will consider her an inspiring muse, or worse, a banal imitator, without ever attempting to analyze her artwork independently of her husband's, or on a level playing field. Even after the macabre death of Jackson Pollock (which we have already mentioned in our article on 3 tortured artists with tragic destinies), she found it difficult to assert herself as an independent artist, despite her evolution in autonomy throughout her life, and her refusal to take her husband's surname. One critic even nicknamed her "Action Widow", a contraction of Action Painting (an artistic practice of which Jackson Pollock was the major figure) and widow, to emphasize Lee Krasner's particular dependence on her late husband. A deeply misogynistic attitude, symptomatic of a patriarchal society completely unabashed.

Lee Krasner, Siren, 1966. Barbican Center, London.

Lee Krasner, Siren, 1966. Barbican Center, London.

As a conclusion, let's remember that these 4 talented artists are not the only collateral victims of their husband's triumph. The list can never be exhaustive, but let us quote for example Dorothea Tanning, wife of Max Ernst, Jean Cooke, wife of John Bratby, or Elaine de Kooning, wife of Willem de Kooning...

In fact, they are so numerous that their disfavor cannot be simply due to coincidence. It' s the bitter symbol of a commonly accepted behavior, of a time when men, by fear or by contempt, didn't want to recognize the place of women artists that they deserved. Today things are changing, and every day we can discover the story of a new woman artist, rediscovered in her time, and rehabilitated in her influence. Let's hope that the past belongs only to the past, and that the mistakes of yesterday will not be repeated.

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)